The opposition to CAFTA in Costa Rica: Institutionalisation of a social movement

All the versions of this article: [English] [Español] [français]

The opposition to CAFTA in Costa Rica: Institutionalisation of a social movement

Ma. Eugenia Trejos [1]

August 2007

1. The negotiating and decision-making process around CAFTA

The US-Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) was negotiated in 2003 and early 2004. Five Central American countries (Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Costa Rica) participated at first. Then the Dominican Republic joined in, having first negotiated an FTA with the United States and then joining the other countries.

The negotiation on behalf of Costa Rica was led by a team of professionals from the Ministry of Foreign Trade (COMEX) who were linked to the interests of large transnational corporations and who, in several cases as became known later, were paid handsome bonuses by the Costa Rica-United States Foundation, heir to USAID (US Agency for International Development). The country therefore carried out a strategic negotiation through personnel paid by its counterpart.

The negotiating phase was not at all simple. From the outset, various sectors called for the opportunity to participate in defining at least the minima or maxima of what would be negotiated, and to be able to closely monitor the process. COMEX established a "consultation" mechanism through which invited organisations were made to appear as participants in the process. Nevertheless, hundreds of recommendations were made without the government committing itself definitively to any of them. In other words, the consultation mechanism was purely formal in terms of representation from popular sectors. Announcements were published in some national newspapers, various sectors were called upon to make their views known without being told how their views would be dealt with, information forums to update representatives of various organisations on the negotiation process were held, and a so-called "side room", an area where the negotiators could talk to organisations and companies (which could afford to participate) on the course of the negotiations, was set up. As before, there was no procedure to make any binding commitments or to even try achieve any form of agreement between negotiators and social organisations.

Popular movements were treated as mere recipients. Their well substantiated arguments , were never taken into account. This became even more evident when the text of CAFTA was published, well after negotiations had been concluded, since during the talks the texts were declared "confidential" in order to "not disclose the national strategy", even for members of parliament who demanded access to them. For example, in a meeting with Vice-Minister Gabriela Llobet, who was also in charge of environment issues, two organisations were given copies of the environment chapters of the US-Chile and US-Singapore FTAs — in English — and asked to comment on CAFTA. This was despite the fact that Mrs Llobet’s assistant had already stated that there was a draft environment chapter prepared by the US and that she saw no problem in these organisations having access to it in order to give their opinion. [2]

Even after the negotiating process was over, it was not possible to get documentation on the process since it was claimed to have been "lost" with the change of ministers from the past administration. In fact, the only ones who did have access to the negotiation process, as advisers to the government, were representatives of the chambers of commerce. So much so that one of their business leaders is presently the Minister of Foreign Trade.

While the negotiation was completed in January 2004 and the FTA was signed by the President in August of that same year, the text was not sent to the Legislative Assembly for approval until October 2005, due to the growing popular resistance expressing various kinds of contradictions: between the popular movements and the government; between the government and part of the business community; and within the government. The government’s internal conflict ended with nearly the entire CAFTA negotiating team, including the Minister of Foreign Trade, resigning from their positions.

The final impetus to CAFTA came from the current government of Oscar Arias, who took office in May 2006 in the midst of a huge protest march — a first in Costa Rica’s electoral history — after a tight election result (barely a 1% lead over the Citizen Action Party) and enormous questions surrounding the election result and the position of the re-elected president. Arias was reinstated by the Constitutional Chamber overturning a legislative decision of 1969. (Arias had already been president in the years 1986-1990.) For this government, CAFTA is a central issue and it is prepared to secure its approval in any way.

The discussion in Congress began in June 2006 through a procedure that has been described as undemocratic and taken to higher bodies, such as the Constitutional Court. The congressional committee that ruled on the FTA, while it heard some groups opposed to the agreement, it refused to receive more than 60 groups that had requested a hearing, it refused to consult indigenous peoples as recommended by technical legislative counsel on compliance with Convention 169 of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), and it drew up its opinion without having discussed and voted on over 300 pending amendments, not to mention without discussing the contents of the agreement.

Hearings in International Affairs committee | In favour | Against | Neutral or ambiguous | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 35 (58%) | 18 (30%) | 7 (12%) | 60 |

Different sectors of the opposition to CAFTA were thwarted their attempts to be heard, because even those who had access to the committee hearings found that no one discussed nor had any interest in seriously discussing the contents of the treaty. The effort was spent signalling who can speak and lawmakers were restricted in speaking because their time was being measured and each person’s slot included time for answers. The discussion was a "democratic" farce and this reinforced the picture that the country was changing direction: democratic institutions that had previously hindered the adoption of the agreement were finished and a continuous stream of rigged and authoritarian procedures took their place.

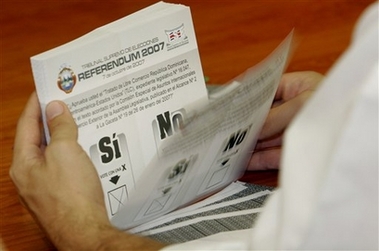

The growing opposition to CAFTA, despite the multimillion-dollar campaign carried out by its supporters, has led to an increasing polarisation of the country between those who defend and those who oppose the agreement. However, from the ranks of the opposition movement came a proposal that seems to have been taken up by CAFTA proponents as a way to overcome the stalemate: holding a national referendum on 7 October 2007.

2. Reasons for the resistance in Costa Rica: a broadly developed social state

2.1. Wide coverage of social services

The development of the welfare state in Costa Rica, from the mid-1940s until the mid-1970s, led to a significant expansion of public services, comparatively better than that achieved in other countries of the region. Despite the implementation of neoliberal policies, which began in the mid-1980s [3], social indicators are still high: the human development index is 0.838 (Costa Rica is in 47th in the world), illiteracy is barely 4%, approximately 82% of the population is covered by health insurance, life expectancy at birth is 78 years, the percentage of people with access to safe water is 75%, electricity reaches 97% of the population and there are 31.6 telephone lines for each 100 inhabitants. Moreover, the country has among the lowest rates in the continent for electricity, landline, cell phone and internet. [4] This has been possible in the context of a social project that guarantees that certain strategic services are provided by the State, under a logic of solidarity and comprehensive coverage.

This expansion of public services is a central element of the resistance in Costa Rica: people who have had access to these services clearly know what they can lose and have been demonstrating their determination to defend it.

2.2 Broad and prestigious intellectual sector

As part of the social state, Costa Rica developed a university system of high quality and with enough autonomy to allow the emergence of critical thinking in a large group of professionals. This sector took on the task of analysing the FTA in order to facilitate position-taking. This way, opposition to CAFTA not only went well beyond words and based itself on analysis of the text, but as people progressively discovered the content of the agreement, criticism of it grew, as did the concern and commitment of the intellectual sector to get directly involved and block its adoption. From the moment negotiations ended, the production of materials of all kinds began. We have published a lot of books and even more articles, several videos and audio materials, leaflets, flyers, songs, poems, jingles, posters, skits, etc. to share analysis on the FTA’s contents. These materials were disseminated through broad distribution and dialogue with communities, from the nearby central plateau to the most remote rural communities and Indigenous Peoples. Different methodologies of popular education made the highly dense and confusing contents of the 3,000-page agreement easy to understand. In this, we had the support of hundreds of activists who were willing to spend their time, money and knowledge on this work.

The people, already worried and suspicious about the enormous pro-CAFTA propaganda blitz, were able to learn about the treaty’s contents, understand its implications and take a position against it. A process that later resulted in the spontaneous formation of more than 130 patriotic committees across the country began to take root.

2.3 Democratic institutionalization working to a degree

Until the current government, which took office in 2006, democratic institutions were relatively functional in Costa Rica. Parliamentary procedures prevented the adoption of laws or international treaties in haste, and many members of Parliament were opposed to CAFTA. The executive branch was controlled by a sector which clung to the traditional style of governance in Costa Rica, aimed at fostering consensus and at looking for mechanisms to build understanding when faced with the possibility of a social explosion. Thus CAFTA lingered for a long time without a parliamentary debate even starting.

This changed with the Arias administration.... But during the period from early 2004 to early 2006, the very rules set by the ruling sectors prevented them from advancing on ratification of the agreement. For example, the executive established a “Committee of outstanding persons”, which took a long time to deliver an ambivalent position on the agreement. This provided time to expose better the fundamental impacts CAFTA would have if adopted, and allowed the opposition movement to grow considerably.

3. Diversity and heterogeneity of participation

Representatives of all social movements participated in the movement against CAFTA: labour unions, peasants, students, Indigenous Peoples, cooperatives, environmentalists, professionals, women, some sectors of various faiths, and artists. Three of the four public universities announced their opposition to CAFTA based on in-depth analysis, and in all four of them fronts of struggle against CAFTA were formed. The Ombudsman also took a position against CAFTA and released a comprehensive and detailed report on its contents.

Prominent personalities from the cultural and intellectual spheres (for examples, laureates of national prizes) also joined very actively, as did numerous well-known artists. From the political arena, two former presidents, several former presidential candidates (of large parties), several former heads of public institutions, former ministers and former first ladies also joined. Even within the National Liberation Party, now in power, a united front was created against the adoption of the agreement. Finally, a sector of the business community has played a very prominent role, including rice producers, generic drugs manufacturers, ranchers and so on. An Organization of Costa Rican Businessmen opposed to CAFTA was even formed.

These developments gave great legitimacy to the movement against CAFTA and made the media campaign for CAFTA, which focused its attacks on certain union leaders, believing it will discredit the movement, ineffective. The reality is that more and more people could see that all of these people were joining the movement to reject CAFTA while only big business and government argued in favour. At the same time, a level of mistrust that Costa Ricans have when they feel that someone is trying to impose something on them emerged: a part of the people’s opposition was generated precisely by the multimillion-dollar advertising campaign in favour of CAFTA and by the government’s insistence that the country must approve it. It should be remembered that this government began its operations in a climate of questioning about the presidential re-election and about the outcome of an election supported by only one-fourth of the electorate.

There was also a diversity of forms of participation and expression. Committees and fronts of struggle formed throughout the country, and organised different kinds of activities, usually through personal contact with people and, in that sense, very different from the impersonal way in which the pro-CAFTA bloc reached out, which was mainly through the mass media. [5] This work grew in such a way that each week new committees or fronts of struggle emerged.

4. Organization of the resistance

The resistance to the adoption of CAFTA went through four phases:

4.1 Before the signing of the FTA

During this period, during 2003 and early 2004, the movement was divided mainly between two sectors: those opposed to any free trade agreement with the United States and those trying to incorporate certain provisions in a treaty under negotiation. Thus, there was a lot of division and fragmentation, and separate efforts being made to confront a negotiation process.

Neither sector actually knew what was being agreed upon, as people only had access to reports from COMEX and not to documents emerging from the actual talks. Not even those who sought to incorporate provisions and participated in the so-called "side room" had access to documents or to the evolution of the talks, as the negotiating team sought advice and agreement only from industry and concealed information to the rest of the participants .

4.2 Between signature and the February 2006 elections

Once the agreement was signed and finally made public, those who had been involved in position-making and expectation-setting saw the scope of the agreement. At that point, those who had been trying to do damage control and incorporate some less unfavourable provisions on any issue, realised that nothing in CAFTA favoured anyone other than transnational capital and its domestic representatives. At that point, the opposition sector gained a greater unity. The dividing line was now between those who felt the agreement should be renegotiated and those who wanted it outright rejected. Among the former were those who, in the final stage, lead the movement for a referendum.

Still, the opposition sector gained a greater unity than before, and a liaison committee which established mechanisms for linkages between different sectors opposed to CAFTA was formed. These instruments of unity did not account for the entire movement, but they allowed people to organise actions in which everyone could participate.

4.3 After the 2006 elections

The 2006 elections led to the start of the Arias administration, whose central project was the approval of CAFTA and the adoption of implementing legislation. This boosted the unity of the movement against the FTA because there was no possible negotiation with the government and there was no possible renegotiation of the agreement. The government broadened its campaign and made moves for legislative approval of the agreement and the complementary implementing laws. The bill moved through the International Affairs Committee - with the deficiencies that were mentioned earlier on - which, finally, would adopt it and send it to the plenary.

The “NO to CAFTA” movement grew. New coordinators and fronts of struggle were being developed, and two of the largest demonstrations against the agreement were held in October 2006 and February 2007. The demonstrations were mainly held in central downtown San José, but there were simultaneous movements in various parts of the country. The polarisation of the country was increasing, and with it social tension.

Then we went on to the fourth stage.

4.4 Institutionalisation of movement

Within the opposition front opponent against CAFTA, a sector emerged pushing for a referendum. When the idea was first broached, before the 2006 elections, there might be some arguments in its favour, but it was an issue that divided the movement. However, when a proposal from civil society to hold a referendum which would define the future of CAFTA was presented to the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), the country had just gone through an electoral process, re-electing President Arias, in which the role of the court had been extremely challenged. The request was initially rejected by the TSE.

But after the mass demonstration of February 2007, in apparent agreement with the government, the TSE approved the holding of a referendum. It would be convened by President Arias and ratified by the Legislative Assembly, and was scheduled for October 2007. With this resolution, in our view, the movement was institutionalised: the rulers had appropriated the struggle and shifted it to their own camp.

As some predicted, the conditions under which the referendum was to be conducted in Costa Rica did not ensure balanced participation. First, the media with the greatest reach were clearly in favour of CAFTA and did not report on or provide access to the opposition movement. Second, the TSE did not give equal access by the two camps to the media, nor did it provide resources that could be used to expose different views. As a result, the pro-CAFTA camp had a multimillion dollar warchest provided by the corporate sector, while opponents had to continue on the basis of personal work or small groups. Thirdly, the Court ruled that the referendum prosecutors would be nominated by the political parties, which hampered the work of the opposition movement since it was not registered among any of them. Fourth, the TSE issued rulings that sought to prevent the participation of the public universities, alleging that they use public resources in a clear and dangerous violation of university autonomy, while accepting that the President and his Ministers use their time — and the public’s resources — to campaign in favour of the FTA. "We’re going to make a deal," Arias said in an official meeting with citizens of a far-off community in the southern part of the country. "You vote in favour of CAFTA and we will build you a big airport."

Thus, the future of CAFTA was decided through an electoral process and not on the basis of a social struggle that had been developing. This process had no baseline conditions to guarantee that people could access information from both sides of the debate and there were well-substantiated doubts about the TSE’s impartiality in the outcome of the process.

However, both the movement and social organising grew during this period, with the creation of even more committees and ways of exposing the contents of the FTA. This movement could be the germ of a process that, beyond the adoption or rejection of CAFTA, leads to a societal transformation that is more radical.

5. A frustrating but hope-giving outcome

CAFTA was approved on 7 October 2007 with a majority vote in its favour. While technically speaking there was no direct fraud at the polls, we can confidently point to unequal conditions of the two sides and media fraud. In the future, the government will be under the close watch of the social movement that grew in this fight that opened new spaces to imagine a different model of society. So what is the situation one month after the initial shock from the outcome of the referendum experienced by the ranks of the NO camp?

The referendum: legitimising the neoliberal project

The NO movement, with its rich social and cultural life, with its alternative ways of participating in national political power, held its space away from the institutions controlled by the ruling classes, as it had been until then. However, the convening of the referendum used ideological arguments that are deeply rooted in our people and there were very few people who saw it as a demobilisation and a trap.

Oscar Arias had already used the machinery of "electoral democracy" against the popular movement when he "saved" the US war against the Sandinista government by proposing a general election. His experience in these fields and in the development of strategy — apparently in collusion with the TSE, the chambers of commerce, the US Embassy and the national and international media — could not but lead to the legitimisation of CAFTA, which has now been adopted by a "majority" vote in the country. Even the Constitutional Chamber participated in this strategy by abstaining from pointing out the overwhelming unconstitutionalities of the FTA.

The process of the referendum was, like our national elections, plagued with anomalies. First, because the TSE was not impartial:

- It did not apply any rule to ensure equal opportunities for the two sides in the debate; it published in the major national dailies, as a "summary of CAFTA", a text prepared by the group "State of the Nation", totally biased in favour of the YES position.

- It did not prevent irregularities such as threats and fear campaigns that were unleashed in the country’s workplaces.

- It allowed the interference of sectors that should not have participated, such as public figures from the Bush administration and the US Ambassador who personally participated in advertising campaigns and visits to companies, even when campaigning was officially suspended.

- During that suspension period, the TSE also allowed the President and his brother, the Minister of the Presidency, to go on television in favour of the YES vote, a clear violation of Article 24 of the statutory regulations of the Law on Referendums.

Second, because the media did not provide access to the information that the public had the right to know.

Third, because the government participated fully and with all of our resources in the YES campaign, using every mechanism to generate threats and fears, under the full view and with the permission of the TSE.

Under these conditions, no one could expect the NO camp to win — and we don’t even know if it did, since we did not have adequate representation in the polling stations.

The patriotic committees: germ of an alternative society

In the Costa Rican landscape of worn out and corrupt institutions, the fight against CAFTA was lost the moment the referendum was agreed to be held. However, it was during the referendum process itself that the so-called patriotic committees gained strength and dynamism.

Most of these committees got involved not only in alternative media but, in autonomy and horizontality, with creativity and space for all participants, without regulations or asphyxiating self-anointed leaders, in the desire and determination that is required to rebuild society. They are, therefore, potential replacements for the existing institutions.

But we can not expect all patriotic committees to follow the same course. There will be those controlled by self-appointed leaders or political parties driven by their own interests. There will be those entangled in the current institutions, lacking the capacity to draw lessons from past experience. But some will be able to recognise the moment when their actions may form the basis of a new institutional framework in which the various popular sectors will be the ones to define and control the direction that the country should take.

Footnotes:

[1] With the collaboration of Eva Carazo, Isaac Rojas, Silvia Rodríguez and Luis Paulino Vargas (in alphabetical order).

[2] Isaac Rojas representing FECON, and Manuel López representing COECOCEIBA-Friends of the Earth

[3] The application of neoliberal policies began in the 1980s and started modifying this orientation. However, social resistance, the style of government and the "buffer" left by previous social policies explain why, at the level of indicators, neoliberalism has not yet had a big impact on the social situation. Nevertheless, because of these new policies, a clear deterioration in the quality of public services, as well as the distribution of incomes and the increasing casualisation of employment are now evident.

[4] Data from: "World Forum on Education: Education for all", country report, at http://www.unesco.org; State of the Nation Programme, at http://www.estadonacion.or.cr; Gerardo Fumero Paniagua, "El Estado solidario frente a la globalización. Debate sobre el TLC y el ICE", San José, Costa Rica, 2006.

[5] We should not overlook the presence of pro-CAFTA elements in a number of companies, where they gave talks to a sceptical audience, whom they terrorised with threats that they would lose their jobs if CAFTA was not approved. Since there are no labour unions in the private sector in Costa Rica (there is no freedom to organise), only the pro-CAFTA bloc had access to companies, which are all in the free [export processing] zones.