What are BITs, FTAs and the TPPA?

Free Malaysia Today | July 2, 2013

What are BITs, FTAs and the TPPA?

Malaysia should learn from Peru’s experience and be most cautious about signing any BITs or FTAs that a company like Lynas may later use against Malaysia.

COMMENT

By Lim Mah Hui

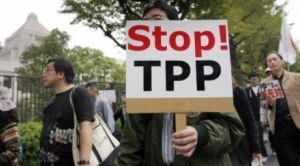

On June 14, 2012, Malaysiakini reported that Malay Economic Action Council representatives walked out of a meeting with the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) because the latter was unwilling to disclose details of their negotiations on the TPPA (Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement).

MITI has been engaging in negotiations on the TPPA for many months and is inclined to sign the agreement.

To a lay person, TPPA, BITs and FTAs are dry and arcane abbreviations that do not interest us. Yet they have serious impact on our lives. So what are they and why should we bother about them?

BITs stand for Bilateral Investment Treaties, FTAs stand for Free Trade Agreements, and TPPA stands for a specific FTA called the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement that is currently under negotiation among a number of Pacific Rim countries including Malaysia.

All these are bilateral or regional agreements signed between countries. The US has been pushing hard for countries to sign such agreements with it.

The current furore over the TPPA arises from a fear that these treaties and agreements may contain provisions on such issues as investment and intellectual property rights that could have adverse consequences on a signatory country’s national policy-making capacity.

For example, the tighter and more monopolistic intellectual property regimes imposed by such agreements could prevent Malaysia from producing cheaper generic versions of essential medicines patented by the major pharmaceutical corporations.

In this article, however, I shall focus only on the investment aspects of these agreements.

In the heyday of economic and trade liberalization, many countries signed bilateral investment and trade agreements with each other to promote trade and investments. There are over 3,000 BITs in existence.

The purpose of BITs (as well as the investment chapters in FTAs) is to promote and protect the investments that one country has in another country. However, it is now recognized that the first generation BITs are one-sided; they protect the interests of private investors at the expense of public interests.

Many governments that have signed such treaties, without understanding the legal implications, are now paying for the mistakes.

Private companies suing governments

Over the last decade the number of cases private investors have brought against governments under BITs has risen over 500% – from 69 cases in 1999 to more than 370 cases today.

Many of these suits involve billions of US dollars in settlement and constrain the capacity of governments to act for public interests.

The following examples illustrate the problems.

The tobacco company Philip Morris has brought an investor-state claim against the Uruguayan government for requiring the company to display graphic health warnings on its cigarette packs.

Similarly it has sued the Australian government for billions of dollars for breach of the Hong Kong-Australia BIT after the government passed a law that required plain packaging for cigarettes. The company argued these requirements violated its trade mark, intellectual property and hence its investment rights.

In Peru, Renco, a US smelting company, sued the Peruvian government under the US-Peru FTA and is demanding US$ 800 million in compensation for failure to grant a 3rd extension of its environmental remedy obligations.

Renco’s smelting site in Peru is among the 10 most polluted sites in the world and it was reported that 99% of children in this area suffer from lead poisoning.

Malaysia should learn from Peru’s experience and be most cautious about signing any BITs or FTAs that a company like Lynas may later use against Malaysia.

Closer to home in Indonesia, in June 2012, Churchill, a UK mining company, sued the Indonesian government for US$2 billion because the local government in Busang (East Kalimantan) revoked the concession rights held by a local company in which it has invested.

There are two models of BITs – the Freedom of Investment (FOI) model and the Investment for Sustainable Development (ISD) model.

The FOI model assumes all investments are good and promote development; hence governments should completely liberalize all investments. Often this not only runs counter to public interest but provisions in BITs are often in conflict with the constitutions of host countries and undermine their sovereignty, as South Africa has discovered.

The ISD model is more selective, recognizing that the effects of foreign direct investment (FDI) on host countries are not all positive and any benefits are not necessarily automatic; thus, regulations are needed to balance the interest of investors and the public interest.

The South African lesson

Malaysia would do well to learn from South Africa’s experience with BITs. In the early 1990s, South Africa in its eagerness to attract FDI and to join the international economic community signed about 15 BITs mainly with European countries. It soon discovered there was no relation between signing BITs and inflow of FDI.

Worse still, it was later confronted with several legal challenges brought by private investors under various BITs.

In 2008, it reviewed all the BITs signed and found many problems with the nature of these bilateral agreements. These include:

– the overly broad definition of investments to cover not only direct investments but also franchises,

– licenses, intellectual property and all types of financial instruments including derivatives;

– the “fair and equitable” treatment clause has been used to challenge the host government’s rights to enact regulations to protect public interest;

– the definition of “expropriation” includes not only direct but also indirect expropriation that can cover any policy measures that affect potential and future profits of investors.

The South African government was most concerned with investor-state dispute provisions in BITs that provided precedence of narrow commercial interests over the host country’s national interest.

The review also revealed weaknesses in the international arbitration process. Investors sue governments in international tribunals whose proceedings are not transparent and are riddled with conflict of interests.

Many of the judges who sit on the tribunals are also lawyers who sometimes represent investors who sue governments.

After several years of discussion and review of BITs, with the help of international experts, the South African government has concluded the following:

– It would review all first generation BITs with a view to renegotiating or exiting them

– It would refrain from signing new BITs except in cases of compelling circumstances

– It would strengthen domestic legislation to include relevant provisions of BITs to protect foreign investors without sacrificing sovereignty. Important issues involving matters of national security, health and environment will be carved out as legitimate exceptions to investors’ protection

– All decisions in respect of BITs will be made at inter-ministerial level and not just by one ministry.

Conclusion

Malaysia is one of the few countries that had successfully imposed capital controls and implemented counter-cyclical fiscal policies during the Asian Financial Crisis that contributed to its rapid economic recovery.

But such policy options for capital controls may not be available if Malaysia signs the TPPA that conforms to the US model.

The TPPA is much more restrictive than the World Trade Organization rules governing trade and investments such that even the IMF is concerned about the lack of policy space for countries signing the TPPA to introduce safeguard measures to meet balance-of-payments problems.

Malaysia should learn from South Africa’s experience.

We call on our parliamentarians to raise and debate this issue in Parliament, to review all existing BITs and FTAs to which Malaysia is a party, and to not allow government authorities to rush into signing any new treaties such as the TPPA that could endanger Malaysia’s interests.

Lim Mah Hui is a city councillor for MPPP and senior advisor to South Centre, Geneva. He was formerly a professor and international banker. This article was first published in the Edge on June 24, 2013.