A struggle for survival in Colombia’s countryside

Eyes on Trade | 30 Aug 2013

A struggle for survival in Colombia’s countryside

Julia Duranti, Witness for Peace Colombia International Team

Though you wouldn’t know it from most English-language media or from heads of state, last week tensions in Colombia’s countryside came to a head. But not between the military and armed groups like the FARC, the usual suspects in foreign reporting on Colombia. The source of this uprising lies in policies not up for discussion in the country’s current peace talks: the impact of the U.S.-Colombia FTA – implemented in May 2012 – and policies that have similarly afflicted Colombian campesinos (small-scale farmers).

Colombia’s campesinos launched the protests – which have overtaken the nation – because they perceive the FTA, and policies like it, to be a threat not just to their production, but their very existence.

The National Grassroots and Agrarian Strike began on August 19 when over 200,000 potato, rice, fruit, coffee, dairy and livestock farmers; miners; truck-drivers; teachers; healthcare workers; and students left their work activities and blocked roadways in 30 key corridors around the country, with the provinces of Boyacá, Valle del Cauca and Nariño being most affected.

The diverse protesters’ list of demands includes suspension and renegotiation of the U.S.-Colombia FTA, financial and political support for agricultural production, access to land, recognition of campesino, indigenous and Afro-descendant territories, the ability to practice small-scale mining, the guarantees of political rights of rural communities, and social investment in rural areas, including in education, healthcare, housing and infrastructure.

Along with roadblocks and marches, in symbolic acts intended to express their inability to earn a living and their frustration at government inertia, dairy farmers in Boyacá poured out over 6,000 liters of milk while citrus farmers in Valle del Cauca dumped 5,000 tons of oranges onto the highway.

What could possibly bring farmers to willingly destroy their own products? Campesino livelihoods have been devastated, a process that began with economic liberalization under President Cesár Gaviria in the early 1990’s and continued with a host of Colombian laws that cleared the way for the U.S-Colombia FTA. Then came the FTA itself. Just over a year old, the deal is already taking its predicted toll on Colombia’s countryside. An FTA-enabled influx of heavily-subsidized U.S. products has contributed to the breakdown of Colombia’s local economies and the displacement of its farmers, fueling the urgency of the current protests.

Despite promises of more jobs and increased exports, the balance after year one of the U.S.-Colombia FTA is dismal for Colombia. According to Colombian paper El Espectador, Colombia’s exports to the U.S. actually fell 4.5% between May 2012 and March 2013, while Colombia’s imports from the U.S. rose 19.7%. In the agroindustrial sector on which many Colombians depend for their livelihood, U.S. imports from Colombia rose 11.5%, but Colombian imports from the U.S. skyrocketed 70%. An economic study conducted prior to the FTA’s passage predicted that just such a scenario would lead to income losses of up to 70% for the vast majority of Colombia’s farmers, contributing to their displacement.

It is not only that strikers feel they cannot compete with heavily-subsidized U.S. production: they are actually prohibited from doing so. The FTA prohibits the Colombian government from subsidizing agriculture for export or domestic consumption, even as the U.S. government subsidizes U.S. agribusinesses to the tune of $15 billion each year.

Along with the FTA came Colombian laws that cleared the way for the deal’s implementation and that similarly plagued campesinos. These include:

– Prohibition of the production, marketing and consumption of panela, a semi-refined sugar that is a Colombian staple (Resolutions 002546 of 2004 and 0779 of 2006)

– Prohibition of the sale of raw milk (Decree 2838 of 2006)

– Limits on the ability of small-scale farmers to raise and slaughter cattle (Decree 1500 of 2007)

– Prohibition of the production and marketing of heritage-breed chickens (Resolution 000957 of 2008)

– Controls on the production, use and marketing of all seeds in the country (Resolution 970 of 2010)

– Expansion of intellectual property rights to include seeds (Law 1518 of 2012).

All of these laws favor large-scale industrial production over small-scale producers that do not have the resources to comply with such regulations. Campesinos are incredulous: “When we produce things like milk or chickens for our communities, of course we ensure that those products are safe because our families are the ones consuming them. It is an economy based on trust. But these new laws destroy that,” expressed one community member in Cauca to a recent Witness for Peace delegation.

Whereas Colombia used to meet its food production needs internally, it is now importing food, including the coffee for which it is so famous. The “mining engine” promoted by the Santos administration as a mechanism for economic growth focuses entirely on resource extraction to generate wealth, using the profits to import almost everything else. This includes replacing land that was previously used for food cultivation with palm oil and sugarcane monoculture for biofuel production. Left landless and without their livelihoods, rural communities are forced to migrate to cities, where they face urban poverty and social breakdown.

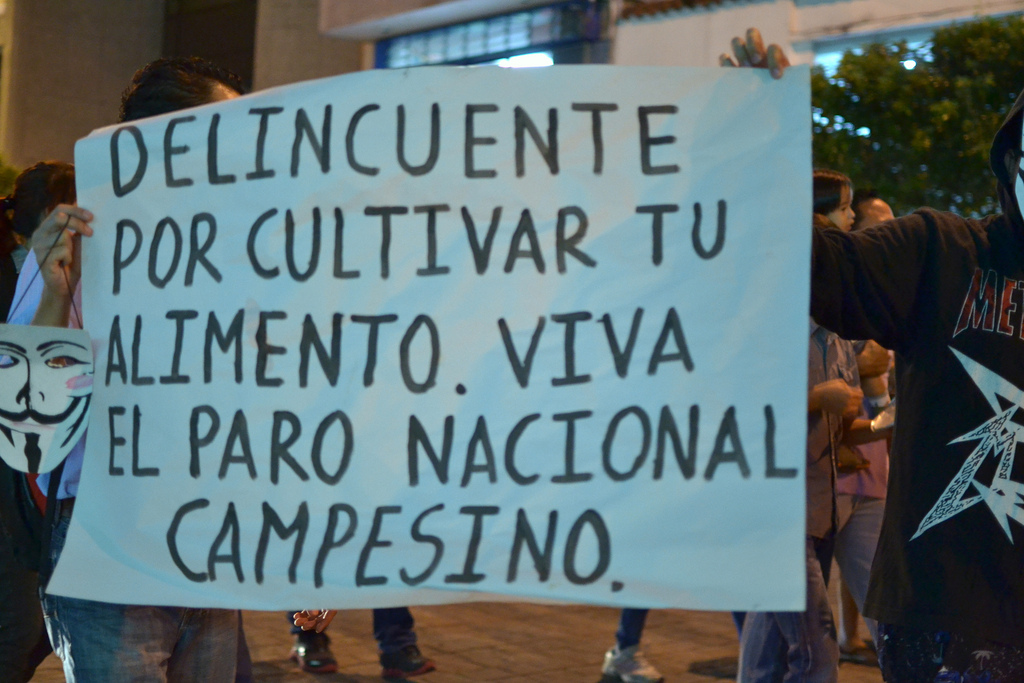

Protestors and their allies recognize that the effects of such policies are not confined to rural areas and that they are already spreading to Colombia’s working class and urban dwellers as well. In a march of solidarity through the capital of Bogotá on Sunday, protestors carried signs defending food security, small-scale producers, and Colombia’s national sovereignty, chanting, “Amigo mirón, únase al montón. Su abuelo es campesino y usted trabajador.” “Bystander, join the struggle! Your grandfather was a farmer and you are a worker,” and, “Queremos papa. Queremos maiz. Multinacionales fuera del pais.” “We want potatoes, we want corn—multinationals, get out of our country.” They made their way peacefully to the central Plaza de Bolívar to share their message with their government, a government that wants to pretend that they don’t exist.

In spite of President Juan Manuel Santos’s claim on August 25 that “the supposed agricultural strike doesn’t exist,” since day one of the protest his administration has met peaceful protestors with extreme repression by the Army, police and anti-riot police (ESMAD). Reports indicate that clashes between protestors and public security forces have claimed five lives, wounded hundreds on both sides and led to over 175 arrests, including four human rights workers and six journalists, who had their equipment confiscated.

Protestors have been fired upon by public security forces using rubber bullets and even, in some cases, live ammunition. Police forces have also fired tear gas at protestors, including from helicopters. Protestors have been threatened, intimidated and had their food supplies stolen by police, who have used broad interpretations of anti-terrorism legislation passed two years ago to detain demonstrators on public roadways on the basis of anything from disrupting public order to terrorism. Predictably, Defense Minister Juan Carlos Pinzón claimed the strike has been infiltrated by the FARC.

The government’s response has been incoherent – attempting to paint the strike as simultaneously nonexistent yet infiltrated by terrorists, as insignificant yet necessitating 16,000 troops in full riot gear using brutal repression tactics. Meanwhile, the government has so far ignored the calls of coordinators for national-level negotiations related to economic and agricultural policy. The government has extended some offers of negotiation at the local level, as in the provinces of Cauca and Boyacá, only under the condition that protestors remove their roadblocks. But protestors, weary of similar offers made in the past that were not followed through, refuse. As potato farmer Cesár Pachón said, “We’re not asking for more money. We’re asking for conditions and agricultural policies that allow us to survive.”

The current strike, therefore, represents more than a demand for agricultural subsidies or protections for certain industries. It is a response to a neoliberal model whose relentless crusade for natural resources and whose stark social inequalities are at the heart of Colombia’s conflict; a response to a model that has no room for the small-scale production that defines the livelihoods of campesinos.