IP Watch | 23 March 2016

What to watch out for in the EU-Mercosur FTA negotiations: consequences for access to medicines

By Marcela Fogaça Vieira and Gabriela Costa Chaves

This week (20-24 March), a new round of negotiation of the free trade agreement (FTA) between Mercosur and the European Union (EU) is taking place in Argentina. For almost two decades, the negotiation of bilateral trade agreements (FTAs), outside of the multilateral international institutions, has been part of the strategy of high income countries to extend the monopolies of major pharmaceutical companies, through intellectual property and regulatory measures. Will the Mercosur/EU FTA have consequences on access to medicines in Latin America countries? After the release of the draft agreement by the European Commission, and through projections made on HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C and cancer medicines, we tried to evaluate the impact of one of the TRIPS-plus measures of the Mercosur/EU FTA on the prices of medicines in Brazil. Per our calculations, an additional USD 444 million would be necessary to be spent by the public health system for the purchase of 6 medicines alone[1]!

Since the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) was signed at the end of 1994, there have been increasing debates about the implications that granting patents for pharmaceuticals have on access to lifesaving medicines and to health-needs oriented innovation. By now, it is widely recognized that patents have a negative impact on access to medicines, as they limit the number of producers and allow for the possibility of setting sky-rocket prices, and at the same time they do not promote innovation necessary to treat most of the health problems of the world population.

International organizations, including United Nations (UN) agencies, World Health Organization (WHO), World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and the WTO itself, have produced many reports and recommendations for countries related to the relationship between intellectual property rights (IPR) and access to medicines. They all have made several statements against the adoption of TRIPS-plus measures, which can further hinder access to medicines and delay health-needs oriented innovation.

The last main report, produced by the United Nations Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines, was released in October 2016[2] and once again recommends caution with the adoption of TRIPS-plus measures and says that an impact assessment should be made before the adoption of any such measure.

Considering the ongoing negotiations for FTA between the Mercosur Association (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and now Venezuela) and the European Union (EU), it was considered relevant to develop an analysis and impact study of the TRIPS-plus provisions being proposed.

EU-Mercosur FTA negotiations

The negotiations around a FTA between the EU and the Mercosur Association began in 2000. In 2004 the negotiations were suspended and were officially relaunched in May 2010. 26 negotiating rounds (including the bi-regional negotiations committee – BNC) took place since then, the last one being in October 2016 in Brussels, Belgium[3]. The next round is scheduled to happen in the end of March 2017 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The objective is to negotiate a comprehensive trade agreement, covering not only trade in industrial and agricultural goods but also services and government procurement, as well as improvement of rules on intellectual property, customs and trade facilitation and other technical barriers to trade.

Breaking a well-known and long criticized trend of non-transparency in negotiations of trade agreements, the EU released in September 2016 a proposed text for three chapters of the future agreement. The released chapters deal with: i) intellectual property rights (IPRs)[4], ii) small and medium enterprises (SMEs)[5] and iii) state-owned enterprises[6].

An analysis based on the draft proposal of the chapter on IPRs released by the EU shows that some of the main TRIPS-plus measures historically pushed for by countries such as the United States or the EU are being again proposed at the EU-Mercosur FTA. Other chapters well-known to also contain worrisome measures for access to medicines, such as the chapter on investments, were not made public.

In short, the main worrisome provisions to watch out for in the EU proposal for the FTA with Mercosur from an access to medicines perspective are: i) exhaustion of IPR (limitation of parallel imports), ii) patent term extension due to regulatory delay and iii) data exclusivity.

i) Exhaustion of IPR – parallel imports

Article 3 of the proposal establishes that parties must adopt national or regional exhaustion of IPR. Under the WTO TRIPS Agreement, members are free to determine the regime of exhaustion of IPR (articles 6 and 28 and article 5d of Doha Declaration).

The problem with national or regional exhaustion of IPR is that it limits the possibility of parallel imports (which allows the importation of products put legally in the market of another country). In case of national exhaustion, no parallel importation is possible; in case of regional exhaustion, it is still possible to import from countries within the same region.

It is worth recalling that in 1998, at the apex of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, when President Nelson Mandela changed South Africa’s law to allow for parallel imports and be able to buy cheaper medicines to treat people in need in the country, he was taken to court by 39 multinational pharmaceutical companies accused of violating IPRs. In the 3 years in which the companies tied up this legislation in the courts before they dropped the case, more than 400,000 South Africans died of HIV/AIDS[7], almost all of whom lacked access to lifesaving medicines which were available in richer countries but were too expensive for them to have access, mostly due to IP protection.

ii) Data exclusivity

The EU is also asking for another classical TRIPS-plus provision, data exclusivity. Article 10.2 establishes that parties shall not permit any other applicant to market the same or a similar product, based on the marketing approval granted to the party which had provided the results of pre-clinical tests or of clinical trials for a period of […] years (number of years not determined in the proposal). Additional time shall be added in case of authorisation for one or more new therapeutic indications which are considered of significant clinical benefit. In other FTAs negotiated by the EU, data exclusivity has been established for period of “at least 5 years”. The TRIPS Agreement makes mandatory for members to protect undisclosed test data against unfair commercial use (article 39.3), but does not make it mandatory to provide exclusivity of the data.

The main problem with data exclusivity is that it can delay the market approval of generic medicines for many years or oblige generic producers to duplicate tests against ethical principles of clinical research in humans and raising the price of generics. Within Europe, data exclusivity is currently pointed as one main obstacle to the arrival on market of generics medicines.

There are several studies estimating the impact of TRIPS-plus provisions, including data exclusivity, in health expenditures both in the public and private pharmaceutical market as well as in the domestic production in the Latin American region[8]. For example, in Ecuador, the adoption of data exclusivity in 2008 would result in an increase of USD 24.47 million in the public expenditures on pharmaceuticals by 2020. In Peru, the adoption of data exclusivity for 10 years in 2009 would result in an increase in medicines expenditures (public and private) in 2025 of more than USD 300 million. In relation to the private pharmaceutical market, the adoption would reflect in an increase of 12% of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) under monopoly in 2025, which would result in an increase of 27% of medicines prices.

iii) Patent term extension due to regulatory delay

The EU is proposing an extension of the patent term due to delay in obtaining market approval by national regulatory agencies. There is no proposal of extension due to delay in granting the patent by national patent offices, as seen in other FTAs. Recalling that under TRIPS the term of protection shall not end before the expiration of a period of 20 years counted from the filing date (article 33) and there is nothing related to extending the patent term.

Under article 8.3 of the EU proposal, parties must provide for a further period of patent protection for a medicinal product which is protected by a patent and which has been subject to an administrative authorization. The period of extension is the period that elapses between the filing of the application for a patent and the first authorization to place the product on their respective market, reduced by a period of 5 years. In the case of medicinal products for which paediatric studies have been carried out, further extension of the patent term shall be provided.

An exploratory study conducted by the authors of this article analysed 17 antiretroviral medicines used in Brazil, of which 9 would have their patent extended if this provision had already been in place in 2015. The average extension of the patent term would be 3 years.

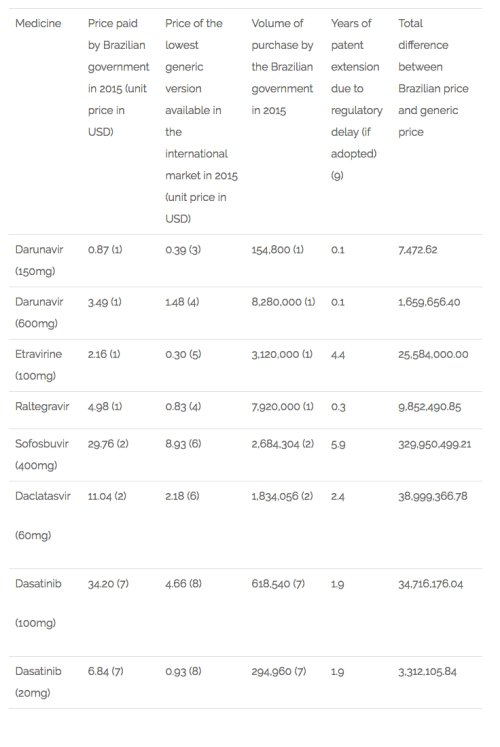

To estimate the implications of this provision in the public expenditures in Brazil, the authors selected 6 medicines adopted by the public health system (SUS) that are subject to patent protection and would have their patent term extended if this provision was already in place in the country. Of the 6 medicines, 3 are used in the treatment of HIV-Aids (darunavir, etravirine and raltegravir), 2 in the treatment of hepatitis C (sofosbuvir and daclatasvir) and 1 for the treatment of cancer (dasatinib).

First, it was estimated the expenditures of those medicines by the Ministry of Health in 2015 based on volume purchased (pharmaceutical units) and the price paid. Then, the same volume was multiplied by the lowest price for generic versions of the medicines available at the international market. After, the difference between the amount paid by the government in that year and the estimated expenditure if Brazil had paid the generic price was calculated. This difference was multiplied by the extra number of years that each medicine would have been under monopoly if their patent term had been extended in the terms proposed by the EU in the FTA, limiting the possibility for the country to purchase or produce generics. The results are impressive: an extra amount of USD 444,081,767.74 would have to be spent by the public health system for the purchase of those 6 medicines alone. Table 1 below details the results.

Table 1 – Estimates of expenditures in Brazil for the purchase of selected medicines as a consequence of patent term extension[9].

With a stronger or weaker language, many reports, declarations, resolutions, recommendations and so on have been produced by international organizations in the past two decades about the impacts of IPR on access to medicines and on the capacity of countries to be able to implement their responsibilities related to the fulfilment of the human right to health. Many of which say explicitly that countries should not adopt measures considered to be TRIPS-plus, that is, that would grant more rights and more protection to intellectual property than what is already established in the WTO TRIPS Agreement. TRIPS-plus measures are generally recognized as measures that would make the situation worse for health, not better. Those same organizations also called for a greater use of the so-called TRIPS flexibilities, which are measures that can be legally adopted under the TRIPS framework to try to make the situation better for health.

However, countries that try to resist the adoption of TRIPS-plus measures or to make use of TRIPS flexibilities still face lots of pressure and threats of retaliation from pharmaceutical companies and governments acting to defend their interests. And there is no real support for them coming from international organizations when it comes to the real case on the ground. As there is nothing being done to stop pharmaceutical companies or governments from pushing for more IPR or for (illegally and immorally) threatening or retaliating against countries that use the TRIPS safeguards. See the current example of Colombia, which is facing huge pressure from the US government and big pharmaceutical companies for threatening to issue a compulsory license for the cancer drug imatinib (for which Novartis, a Swiss company, holds a patent in the country), which, by the way, is off patent protection in many countries. Or the cases in Brazil and Argentina, in which pharmaceutical companies went to court to challenge measures to increase the quality of the examination of patent applications in the pharmaceutical sector, also a recommendation made by the UN SG High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines.

There is an urgent need to take real action against anyone – companies or governments – who retaliate against (or threaten to) the legitimate use of the provisions contained in the TRIPS Agreement that can protect the right to health or that push for the adoption of TRIPS-plus measures that will only bring more suffering and death to millions of people across the world who lack access to necessary medicines. That is, if we still want to believe in a society that cares about taking human rights seriously.

Marcela Fogaça Vieira graduated in Law (2006), specialized in Intellectual Property Law and New Technologies of Information (2010) and holds a Master’s degree in Health Policy and Management. She has been working with access to medicines issues at civil society organizations in Brazil since 2005. She has published several articles in this subject and has worked as consultant for many international organizations. Nowadays, she is a consultant for the Suttleworth Foundation. Her full CV is here.

Gabriela Costa Chaves graduated in Pharmacy (2002) and holds a Masters and PhD in Public Health from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (2005 and 2015). Since January 2013, she has been working as a researcher for the team of the Pharmaceutical Assistance Center of the National School of Public Health – ENSP/Fiocruz. Previously, she has worked with national and international organizations working on access to medicines issues in Brazil.

Notes

[1] The full report (in Portuguese) is available at: http://bit.ly/ftaeumercosur1. And a short video highlighting the main findings of the study and worries around the FTA negotiations is available here (in English, with Portuguese subtitles): https://vimeo.com/209577201.

[2] UN SG HLP on Access to Medicines, Final Report. Available at: http://www.unsgaccessmeds.org/final-report/. Last access on March 7, 2017.

[3] An official report of the XXVIth round of negotiations is available at: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/november/tradoc_155069.pdf. Last access on January 10, 2017.

[4] Available at: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/november/tradoc_155070.pdf. Access on Feb. 21, 2017.

[5] Available at: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/november/tradoc_155071.pdf. Access on Feb. 21, 2017.

[6] Available at: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/november/tradoc_155072.pdf. Access on Feb. 21, 2017.

[7] MSF, Access Campaign. Drop the case! Support the struggle for medicines in South Africa. March, 2001. Available at: https://www.msfaccess.org/about-us/media-room/press-releases/drop-case-support-struggle-medicines-south-africa

[8] Among others: i) Gamba MEC. Intellectual property in the FTA: impacts on pharmaceutical spending and access to medicines in Colombia [Internet]. Misión Salud; IFARMA; 2006. Available from: http://web.ifarma.org/images/files/pintelectual/TLC_Colombia_ingles[1].pdf. ii) Gamba MEC, Buenaventura FR, Bernate IR. Impacto de los derechos de propiedad intelectual sobre el precio, gasto y acceso a medicamentos en el Ecuador [Internet]. Fundación Ifarma; OPS; 2010. Available from: http://web.ifarma.org/images/files/pintelectual/Impacto_de_los_derechos_de_PI-Ecuador_final_diciembre_2010.pdf. iii) Gamba MEC, Cornejo EM, Bernate IR. Impacto del acuerdo comercial UE-países de la CAN, sobre el acceso a medicamentos en el Perú [Internet]. AIS-LAC, Fundación IFARMA, Fundación Misión Salud, Health Action International; 2009. Available from: http://web.ifarma.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=56:impacto-del-acuerdo-comercial-ue-paises-de-la-can-sobre-el-acceso-a-medicamentos-en-el-peru&catid=9:propiedad-intelectual&Itemid=294. iv) Hernández-González G; Valverde M. Evaluación del impacto de las disposiciones de Adipc plus en el mercado institucional de Costa Rica. 2009. Cinpe, ICTSD, OPS, PNUD. Available at: http://web.ifarma.org/images/files/pintelectual/final_31_julio_09.PDF. v) Rathe M, Minaya RP, Guzmán D, Franco L. Estimación del impacto de nuevos estándares de propiedad intelectual en el precio de los medicamentos en la Republica Dominicana. 2009. Fundación Plenitud, ICTSD, OPS. Available at: http://web.ifarma.org/images/files/pintelectual/informe_final_1.pdf.

[9] Sources: 1) Brazilian Ministry of Health, HIV-Aids Department (DDAHV/SVS/MS), 2016. Obtained via Access to Information Act. 2) Brazilian Ministry of Health, Departamento de Assistência Farmacêutica, 2016. Obtained via Access to Information Act. 3) MSF, Decisions around HIV treatment in 2015: Seven ways to fail, derail or prevail, 2015. 4) WHO-GPRM. 5) MSF, Untangling the Web, 18th edition, 2016. 6) HepCAsia, Generic DAAs Pricing. Sofosbuvir as of May 2015. Daclatasvir as of January 2016. 7) Brazil Federal Government. Portal da Transparência Federal – Ministério da Saúde. 8) Mims.com apud t’Hoen, Access to cancer treatment, 2014. The price of the generic version was from 2013 and for the 50mg tablet (unit price US$2.33). For the purposes of this study, we considered the price per mg to calculate the generic price of the 20mg and 100mg tablets used in Brazil. 9) Calculated by the authors based on registration information obtained at ANVISA website and patent information obtained at INPI website.