Even before the World Trade Organization (WTO) lurched into its current state of crisis, bilateral FTAs had become a tool of choice for corporate and state interests seeking to expand intellectual property rights (IPR) standards. IPRs confer monopoly rights over intangible goods and services — methods of doing business on the internet, trademarks, computer programmes, designs, manufacturing processes, drug formulations or types of rice. They give IPR owners the right to prevent anyone from making or using their "creation". As such, they provide companies a direct tool to control a portion of the market, to block out competition and to fence off territories. Ironically, while IPR chapters are key aspects of many “free” trade and investment agreements, they are little more than protectionism for transnational corporations (TNCs), administered by governments. TNCs argue that without monopolies, there will be no innovation. Sharing should be banned; only capitalistic trade based on exclusive private property should be the norm.

Through FTAs, bilateral investment treaties (BITs) and other forms of direct agreements between countries, the US and Europe are insisting that the partner country adopt their standards of IPR protection and enforcement. This process has happened multilaterally via the WTO and the World Intellectual Property Organization. But it is now being pushed very aggressively through unilateral, bilateral and regional agreements — deals which go much further than the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related aspects of Intellectual Property rights (TRIPs). FTAs are setting “TRIPs-plus” standards.

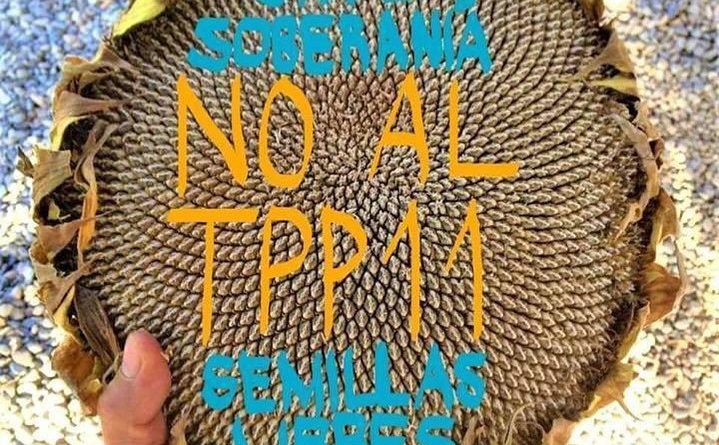

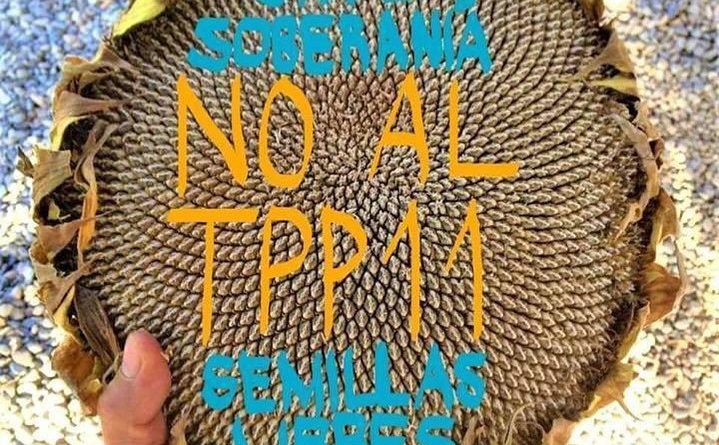

The US imposes patents on plants and animals in its FTAs, while the EU and Japan, for the benefit of their biotech companies, push the UPOV Convention, a set of patent-like rules to prevent farmers from saving seeds. Meanwhile, pharmaceutical corporations have turned to FTAs as tools to impose stricter rules preventing the manufacture and trade of generic drugs. For many countries, and many peoples, these propositions are nothing short of revolutionary. Because it means they have to

– extend protection for branded drugs and limit parallel imports, hampering the availability of affordable generic medicines

– start patenting plants and animals, which means farmers cannot save seed or reproduce fish breeds or livestock

– get rid of screen quotas that give preference to the showing of local films

– start patenting computer software, to the detriment of local programmers and the creative open source movements now mushrooming up across the world as a cheaper alternative to Microsoft

– extend copyright protection, which already causes serious problems for students, libraries and educational institutions

– clamp down on piracy of popular consumer goods like digital products, clothing and music

– make IPR infringements criminal offences, even though IPR is part of civil law

and the list goes on.

Through IPRs, corporations seek monopoly control over vast areas of life. They expect that we should all regularly pay them licenses to use their products and to reimburse their research and development costs. Never mind all the public subsidies, tax breaks, university contract labour and so on that go into their research and development in the first place. IPR laws being pushed through bilateral channels make it public policy that countries should protect the TNCs, the real pirates.

Because of the serious implications that ‘TRIPs-plus’ IPR chapters of FTAs have for broad cross-sections of societies, in some anti-FTA struggles, such as the fightback against the US-Thailand FTA, farmers and people living with HIV/AIDS have joined together in their opposition of this new threat to their survival. Concerns have also been raised about the way in which the EU’s EPAs include TRIPs-plus provisions, while Indigenous Peoples in many countries continue to assert alternative frameworks for the use and sharing of traditional knowledge that challenge the capitalist, commodified logic of “intellectual property rights” enshrined in free trade and investment agreements.

More recently, a new development in transnational IPR enforcement has sparked opposition and controversy, including major protests in many European cities. In October 2011, after a secretive negotiations process, the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA) was signed by a number of countries and will come into effect once six countries have ratified it. ACTA would potentially set up a new international legal framework for enforcing IPR. Opponents have criticized the agreement’s impact on privacy, freedom of expression and internet freedoms, and generic drug manufacturing.

last update: May 2012

Photo: Chile Mejor Sin TLC