From the indigenous peoples’ environmental catastrophe in the Amazon to the investors’ dispute on denial of justice: the Chevron v. Ecuador August 2018 PCA arbitral award and the dearth of international environmental remedies for private victims

EJIL: Talk! | 13 September 2018

From the indigenous peoples’ environmental catastrophe in the Amazon to the investors’ dispute on denial of justice: the Chevron v. Ecuador August 2018 PCA arbitral award and the dearth of international environmental remedies for private victims

by Diane Desierto

The recent 30 August 2018 Chevron v. Ecuador arbitral award is yet another example of the ongoing asymmetries of protection in the much-beleaguered investor-State dispute settlement system, in which States have generously afforded protections to foreign investors to bring suits directly against States, without creating parallel avenues for affected local communities and/or indigenous peoples to initiate arbitration proceedings directly against either foreign investors or irresponsible States. Despite all our collective best efforts at ongoing reform in UNCITRAL (see updates on Working Group III’s mission on ISDS Reform here), ICSID (see their latest rules amendment project here) and elsewhere, I retain serious doubts as to whether investor-State dispute settlement could ever symmetrically represent the environmental and cultural interests of indigenous peoples and local communities, as effectively as it does investors’ claims to treaty protection and (significantly substantial) compensatory relief. Today, environmental plaintiffs have to navigate between an unwieldy, unpredictable, and quite disparate mix of remedies before domestic (administrative or judicial) courts or tribunals of their home States, potentially some regional courts (such as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights) or treaty monitoring bodies (whether those specifically created in environmental treaties or human rights treaties), other foreign courts in other countries that permit some environmental tort claims, and possibly, any cases that their home State can bring under diplomatic protection to pursue remedies against foreign nationals or the home States of these foreign nationals. And all these frequently take place in the context of abject differences of power, resources, and capacities between environmental and human rights victims as claimants against either States and/or foreign investors, vis-a-vis foreign investors as claimants or States as respondents. It’s not at all hyperbolic to observe that, with respect to the international environmental system, the deck already appears heavily stacked against environmental plaintiffs at the outset.

The Chevron v. Ecuador arbitration presents a crystal example of how what was originally an environmental dispute seeking remediation for one of the worst environmental disasters in history involving oil spillage into 4,400 square kilometers of the Amazon rainforest – ultimately mutated into the investors’ denial of justice claim in investor-State arbitration. At least, in my view, while the erudite tribunal in this case thoroughly set out the technical legal reasoning in its award on the precise legal issues of the investment treaty breaches alleged, the award itself more broadly demonstrates that we may well be at the point that a dedicated separate international dispute settlement system might already be necessary to properly adjudicate victims’ claims in human rights and environmental disputes. (Notably, other scholars refer to this dispute to highlight the illegitimacy or alleged exces de poivre of arbitral tribunals making assessments and evaluations of the acts or decisions of domestic courts and judicial systems ipso facto – a significant heavily disputed structural matter about the current investor-State dispute settlement system, which is, however, not the law and policy observation I make here.) Some efforts looking beyond the narrow ISDS framework, among others, include projects such as the drafting of the new Hague Rules on Business and Human Rights Arbitration; the tentative and non-binding 15 September 2016 policy paper of the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court exploring the possibility of prosecuting environmental crimes; as well as the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s suite of environmental dispute resolution procedures (interstate arbitration under environmental treaties, mixed dispute resolution under environmental instruments and contracts, specialized environmental rules for arbitration and conciliation). To date, these initiatives have not gone much further beyond their incubation.

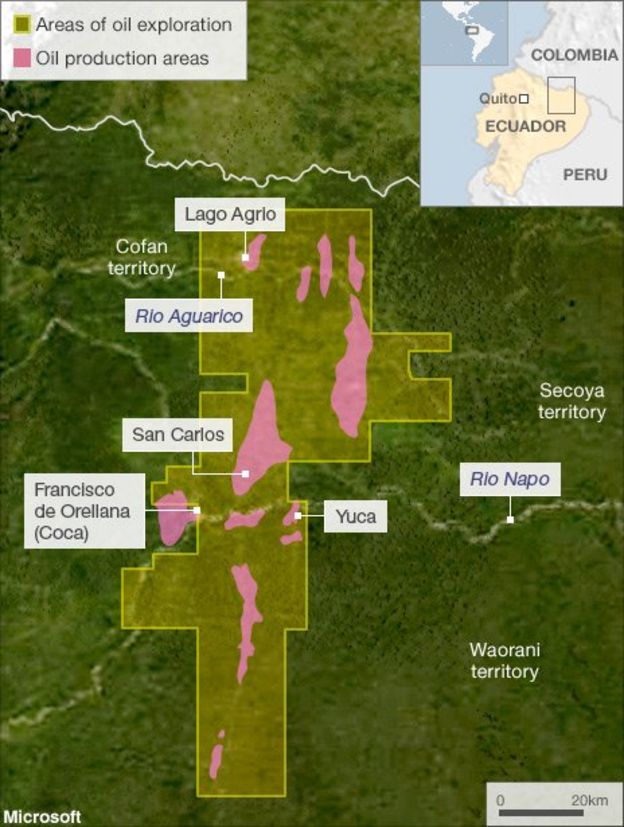

The most difficult aspect of the Chevron v. Ecuador case is the fact that the arbitration turned on the issue of Ecuador’s investment treaty breaches over what Chevron alleged were very troubling serious acts of fraud and corruption committed by lawyers and judges to produce a favorable 2011 Ecuador court judgment for the environmental plaintiffs. The fraud and corruption allegations have long since overshadowed the urgency of decades of environmental damage that have largely gone without significant and continuing remedy, alongside ongoing health problems from toxic contamination that have impacted indigenous peoples and local communities for generations. (Note: this pollution disaster originated long before I or generations of current international lawyers were even born.) The Chevron v. Ecuador arbitration succeeded in laying the blame on Ecuador since, for the tribunal, Chevron had already been released from its obligations of remediation under the 1995-1998 Settlement Agreements. Unfortunately, the arbitral award does not lay out any detailed environmental analysis to explain why contracts such as the 1995-1998 Settlement Agreements would be sufficient to release private parties from short-term, medium-term, and long-term remediation efforts to restore the ecosystem, and whether such releases were at all consistent with international public policy and Ecuador’s own commitments under international law (especially international environmental treaties and customary international environmental law). Neither did the tribunal explore whether Ecuador alone had the right to conclude the Settlement Agreements on behalf of all the environmental plaintiffs and affected communities, or if Ecuador could indeed effectively and exclusively represent the environmental plaintiffs and affected communities in the investor-State arbitration considering how its government agents exercised oversight (or lack thereof) with respect to the environmental disaster. Because environmental plaintiffs, indigenous peoples, and affected communities continue to be dependent on the host State of the investment to vindicate their claims against foreign investors, the investor-State dispute settlement system simply cannot lend any of these environmental, indigenous, and local plaintiffs any real, much less effective, voice over their fight to restore the Amazon to health. While plaintiffs are mired in multiple litigations and arbitrations around the world to seek accountability from either Chevron and its affiliates or their own government in Ecuador, there is virtually no dedicated State, inter-State, regional, or public-private partnership cooperative efforts to try and achieve environmental restoration in the affected 4,400 square kilometers of the Amazon, as depicted in the map below (source here):

Chevron’s investment treaty claims under the 1993 Ecuador-US BIT

To recall, on 1 January 2009, Chevron had initiated the investment treaty arbitration against Ecuador alleging the latter’s breaches of the 1993 Ecuador-United States bilateral investment treaty (BIT). Close to a decade of heated litigation and multiple proceedings before different courts and tribunals thereafter between these parties, on 30 August 2018, the Chevron v. Ecuador Tribunal (composed of Tribunal President V.V. Veeder, Arbitrator Dr. Horacio Grigera Naon, and Arbitrator Professor Vaughan Lowe) issued its 521-page Second Partial Award on Track II issues (hereafter, “Track II Award”) that essentially focused on Chevron’s prayers for relief that it be declared to have “no liability or responsibility for satisfying the (14 February 2011 judgment and 4 March 2011 clarification order of Ecuador’s Superior Court of Justice of Nueva Loja, collectively dubbed the “Lago Agrio Judgment”) because they were fully released for all such claims by the (1995-1998 Settlement and Release Agreements, collectively named the “Settlement Agreements”)” and that “the claims pleaded in the Lago Agrio Litigation (and upon which the Lago Agrio Judgment were based are barred by res judicator and collateral estoppel” (Track II Award, p. 40). The same Track II Award deals with issues also raised by Chevron in the course of the proceedings, such as its prayer that due to “the unique circumstances of this case…[for] a combination of remedies that includes declarative, injunctive, and monetary relief to prevent further unprecedented injury…and to compensate Chevron for losses resulting from Ecuador’s breaches of its contractual, Treaty, and international law obligations” (Track II Award, pp. 41-42). Chevron’s prayer for relief explicitly included items such as: 1) a declaratory judgment from the tribunal that Chevron has “no liability or responsibility for environmental impact, including but not limited to any alleged liability for impact to human health, the ecosystem, indigenous cultures, the infrastructure, or any liability for unlawful profits, punitive damages or penalties, or for performing any further environmental remediation arising out of the former Consortium that was jointly owned by TexPet and Ecuador, or under the expired Concession Contract between TexPet and Ecuador”; a declaratory finding that Ecuador breached the Settlement Agreements and ordering Ecuador’s performance of the Settlement Agreements; 2) a declaratory finding that Ecuador breached obligations under the 1993 Ecuador-US BIT (specifically those on fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, effective means of enforcing rights, national treatment, and observance of investment obligations); 3) a declaratory finding that Ecuador is exclusively liable for the Lago Agrio Judgment and an injunctive order to Ecuador to use all measures necessary to enjoin enforcement of the Judgment against Chevron; 4) and if any court orders recognition or enforcement of the Lago Agrio Judgment, Ecuador should directly satisfy the Lago Agrio Judgment itself, through the specific obligation of Ecuador to pay Chevron the sum of money awarded or paying Chevron any sums that the Lago Agrio Judgment plaintiffs manage to collect from Chevron and its affiliates. (Track II Award, p. 42).

The 1995-1998 Settlement and Release Agreements Signed by Ecuador

Ecuador’s Ministry of Energy and Mining signed the 1995 Settlement Agreement (“Contract for Implementing of Environmental, Remedial Work and Release from Obligations, Liability, and Claims”) with PetroEcuador and TexPet (Texaco Petroleum), explicitly stating that TexPet agreed to do the “Environmental Remedial Work in consideration for being released and discharged of all its legal and contractual obligations and liability for Environmental Impact arising out of the Consortium’s operations….“Environmental Impact” included: “[a]ny solid, liquid, or gaseous substance present or released into the environment in such concentration or condition, the presence or release of which causes, or has the potential to cause harm to human health or the environment.” (Track II Award, p. 108, at para. 3.18). TexPet thereafter settled disputes with four municipalities of the affected Oriente Region (1996 Municipal and Provincial Releases) (Track II Award, p. 110, at paras. 3.25-3.26). On 30 September 1998, Ecuador’s Ministry of Energy and Mining signed a “Final Release” certifying that TexPet had performed all of its obligations under the 1995 Settlement Agreement and released TexPet from any environmental liability from the Consortium operations. (Track II Award, p. 111, at paras. 3.27-3.29).

Litigations in Ecuador Courts and Elsewhere

On 14 February 2011, Judge Nicolas Zambrano Lozada of Ecuador’s Superior Court of Justice of Nueva Loja issued the Lago Agrio Judgment, holding Chevron liable in damages for close to US$18.2 Billion. Years later, Ecuador’s Constitutional Court upheld this Judgment (reducing assessed damages to US$9.5 Billion), ultimately rejecting Chevron’s final appeal last July 2018. The Supreme Court of the United States has upheld the United States’ 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision barring enforcement of the Lago Agrio Judgment, finding that it was obtained through the bribery efforts of the plaintiffs’ counsel, Mr. Steve Donziger and his associates. Pending those proceedings, there were mutual allegations of fabricated reports submitted to courts of the United States as well as further acts of alleged corruption and extortion as the plaintiffs’ counsels sought to enforce the Lago Agrio judgment in various jurisdictions where Chevron has assets. As narrated by the Chevron v. Ecuador arbitral tribunal, the web of lawsuits, arbitrations, prosecutions, and investigations in this dispute spanned the globe – from the Aguinda Litigation in New York, the Lago Agrio Judgment in Ecuador, the ‘commercial cases’ arbitration at The Hague, the Ecuador-US investment treaty arbitration with the Permanent Court of Arbitration, the AAA arbitration in New York, the New York Stay of Legal Proceedings, the Section 1782 Litigation in the United States, the RICO litigation in New York, the Huaorani Litigation in New York, the Veiga-Perez Criminal Prosecutions in Ecuador, the enforcement litigation in Ecuador, the Gibraltar Litigation in Gibraltar, and criminal investigations in Ecuador. (Track II Award, parts IV-020 to IV-041).

Chevron v. Ecuador Dispositif

The Chevron v. Ecuador arbitral tribunal accepted its jurisdiction over the dispute under Article VI (submission of investment dispute), Article II(3) (fair and equitable treatment and non-discrimination guarantees) and Article II(3)(c) (umbrella clause) of the 1993 Ecuador-US BIT (Track II Award, paras. 10.2-10.3). On the merits, the Tribunal declared that “material parts of the Lago Agrio Judgment of 14 February 2011 (as clarified by order of 4 March 2011) were corruptly ‘ghostwritten’ for Judge Nicolas Zambrano Lozada, as a judge of the Lago Agrio Court, by one or more of the Lago Agrio Plaintiffs’ representatives in return for a promise by such representative(s) to pay to Judge Zambrano a bribe from the proceeds of the Lago Agrio Judgment’s enforcement by the Lago Agrio Plaintiffs”. (Track II Award, Part X-1, at para. 10.4). Ecuador was declared to have “wrongfully committed a denial of justice under the standards both for fair and equitable treatment and for treatment required by customary international law under Article II(3)(a) of the Treaty” because it “maintain(ed) the enforceability and executi(on of) the Lago Agrio Judgment and knowingly facilitate(d) its enforcement outside Ecuador”. (Track II Award, Part X-2, at para. 10.5). Ecuador was ordered to “make full reparation” to the claimants Chevron and its affiliates for such breaches (Track II Award, Part X-2, at paras. 10.6. 10.9, and 10.11), and was ordered to take immediate steps “to remove the status of enforceability from the Lago Agrio Judgment as also decided by the Lago Agrio Appellate, Cassation and Constitutional Courts”; “to preclude any of the Lago Agrio Plaintiffs, any ‘trust’ purporting to represent their interests, any of the Lago Agrio Plaintiffs’ representatives, and any non-party funder from enforcing any part of the Lago Agrio Judgment…directly or indirectly”; as well as to take a whole series of other measures that Ecuador should take to inform judicial branches of other States about the invalidity of the Lago Agrio Judgment and to take any corrective measures to wipe out all the consequences of Ecuador’s internationally wrongful acts with respect to the Lago Agrio Judgment and ensure that Ecuador complies with all releases under the 1995-1998 Settlement Agreements [Track II Award, p. X-3-4, at paras. 10.13(i) to 10.13(viii)]. Ecuador’s full reparation in the form of compensation to Chevron, and all other relief sought, will be adjudicated subsequently by the Tribunal.

Participation of Environmental Plaintiffs in the Investor-State Dispute between Chevron and Ecuador

As the punting of legal responsibility between Chevron and Ecuador has demonstrated in the arbitral award, it was obvious from the beginning of this litigation that the environmental plaintiffs represent distinct interests from their home government (which had signed the 1995-1998 Settlement Agreements). The environmental plaintiffs’ call for responsibility appears to have focused mainly on the compensatory damages claims against Chevron and its affiliates, without allocating legal, political, social, and group resources not just to hold all State and non-State entities responsible for the continuing environmental disaster, but to leave the door open for collective cooperation among all stakeholders in the Amazon to respond to the lingering toxic effects of the oil spill that could not have been anticipated when Ecuador signed the 1995-1998 Settlement and Release Agreements. (As an example, 25 years after the Exxon Valdez oil spill, effects on biodiversity, the marine ecosystem, and related public health issues remain). Today’s science involved in environmental threat assessment and environmental remediation would certainly differ from that which was available in the 1990s as to lead Ecuador to conclude that it could release the consortium operator then (TexPet) from all environmental impacts. Because parties have been locked in nonstop adversarial litigation and arbitration for decades with mutual allegations of fraud and corruption, the prospects are murky for finding cooperation on the harder work of achieving long-term environmental remediation; environmental cleanup; environmental surveillance, monitoring and inspections; and ecosystem protection as they affect all stakeholders of the Amazon. The real challenge ahead for international lawyers and international environmental policy professionals is to find where environmental plaintiffs can effectively and legally achieve and encourage such long-term ecosystem cooperation for environmental protection, well beyond the intricacies of legal enforcement of environmental accountability that can span decades and jurisdictions in a relentless war of attrition exhausting all domestic, foreign, and international dispute settlement mechanisms – no matter how inapt they may be to achieve long-term ecosystem protection and redress for environmental victims. Not only has there never been any State or non-State compensatory, administrative, governmental, or remediatory measures of redress afforded to aid indigenous peoples and affected local communities of the Amazon since this disaster in the 1970s, but even today as the invisible college of international lawyers takes up its work in various reform arenas for investor-State dispute settlement or any other international, regional, or local dispute settlement mechanism opened against States – it would serve us well to constantly remember that international environmental plaintiffs to this day do not have a dedicated mechanism or system of redress for continuing environmental disasters such as in the Amazon. In my view, the task no longer lies with interpreting investment treaties alone and trying to reform investment arbitration in general – but designing an entirely cohesive system for international environmental justice that is open to the actual victims of environmental disasters and not just the States that often fail to genuinely represent them.