The pitfalls of bilateral deals

Livemint | Mon, Jan 3 2011

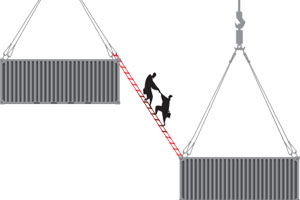

The pitfalls of bilateral deals

Biswajit Dhar

India’s economic integration with several of its partners is set to enter a new phase in 2011 as the country seeks to conclude comprehensive economic partnership agreements (Cepas) during the year. While the Cepa with the 27-member European Union (EU) has attracted the maximum attention, India is on the threshold of concluding agreements with Japan and Malaysia, too. Besides, feasibility studies for engaging in Cepa negotiations have been concluded with several countries, including Australia, New Zealand and Indonesia. India has thus joined the long list of countries that are actively engaged in trade liberalization involving several of their key trading partners. With the multilateral trade negotiations in the Doha Round making very little progress during the past two years and is unlikely to make much headway in the near future unless the US shows real intent, improvements in market access opportunities seem possible only through these bilateral trade deals.

The dynamics of trade liberalization ushered in by these bilateral initiatives seem to support the view that they would act as building blocks for the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) global trade liberalisation agenda. Quite apart from the number of countries that are formalizing bilateral trade deals, it is the nature of these agreements that supports the “building blocks” thesis. Gone are the days when bilateral deals used to be traditional free trade agreements, concerned with reducing and/or elimination of tariffs. Recent agreements are more “comprehensive” in their coverage: Not only do they include a number of areas that are monitored by WTO; they go beyond the scope of the issues included in the Doha Round. For instance, the Cepas that India is negotiating include investment, an area that was excluded from the Doha Round; and in the agreement being negotiated with the EU, government procurement is included. This is there in WTO, too, but as an optional agreement, and India is not party to it.

The Cepas that India has lined up have promising trade prospects. At present, India is a minor actor in the markets of most of these Cepa partners and, therefore, the focus on these countries could help Indian entities explore avenues for gaining better access to these markets. And given that many of these economies have got back their growth momentum after the recent downturn, opportunities are waiting to be exploited there.

It must be pointed out that while the Cepas are useful in lowering or removing most of the impediments at the border, behind-the-border measures adopted by partner countries are generally not addressed systematically in these bilateral agreements. Again, while some of the procedures and controls governing the movement of goods across national borders (the so-called “trade facilitation” issues) are being taken into consideration in order to reduce transaction costs, non-tariff barriers in the form of technical standards and food safety standards have largely remained unaddressed. These barriers are increasingly being used by all major economies and have emerged as the major market access constraints now that most countries have reduced tariffs unilaterally, especially on non-agricultural products. Similarly, in services, market access prospects can be adversely affected by domestic regulations such as qualification requirements and procedures, technical standards, and licensing requirements. These regulations are liberally employed by advanced economies, and are now being put in place by most emerging ones as well.

One of the shortcomings that India suffers from is that concrete steps to meet the challenges posed by the non-tariff barriers in the goods sectors and domestic regulations in the services sectors of partner countries have not been taken. This is despite the fact that Indian industry has been up against these barriers. A slew of measures need to be taken domestically, which include establishment of institutions through public-private partnerships for developing capacities to cope with these challenges.

Some of the Cepas have brought with them a veritable menu of concerns that have been flagged by various constituencies in the country. While specific sectors of the domestic industry have been wary of facing import competition that would accompany market opening, the major concern in agriculture is the effect of trade liberalization on the livelihood of small and marginal farmers. The latter set of concerns gets heightened in case of agreements involving partners such as the EU that have been supporting their agriculture with large doses of subsidies. Estimates provided by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development on farm subsidies provided by the member countries shows that in 2009, support received by the agricultural sector in EU member states totalled $139 billion, about 1% of their gross domestic product (GDP).

As regards intellectual property rights, negotiations with the EU have also brought concerns about intellectual property rights, arising in particular from the position that India’s intellectual property laws need to be amended to meet the demands of global pharmaceutical majors. Meeting this demand would affect the future of India’s generic pharmaceutical industry whose interests were protected by this government when recent amendments to the country’s intellectual property laws were undertaken to make them compatible with India’s commitments under the WTO Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights.