Cambodia, ASEAN likely to teeter off balance with RCEP

Phnom Penh Post - 1 April 2021

Cambodia, ASEAN likely to teeter off balance with RCEP

By Sangeetha Amarthalingam

Four months after RCEP was signed, a study surfaces, with gloomy trade data, portending a shaky future for the Kingdom and ASEAN as a whole

Prominent economist and trade policy scholar Jagdish Bhagwati once likened free trade agreements (FTAs) to “termites” that “eat away” at multilateral trading systems “relentlessly and progressively”.

His remark, which described the title of his 2008 book Termites in the Trading System – How Preferential Agreements Undermine Free Trade, was intuitive in that he talked about how FTAs are “erroneously” pursued by governments in the hope of scoring a free trade agenda.

No doubt, a free trade champion himself, Jagdish conceded that anything less than an inclusive multilateral free trade liberalisation involving everybody was “suboptimal”, economist Jomo Kwame Sundaram quoted him as saying in a virtual conference last year.

Jomo, a former UN assistant secretary-general for economic development, noted that often FTAs are treated as an “obvious no brainer”, and that it is “always beneficial” to everybody concerned.

“But some of the major economic gurus like Paul Krugman and Jeff Sachs have distanced themselves from such simplistic positions.

“The motives are complex but it is important to recognise that there is no consensus as far as the so-called trade theory is concerned and the need for free trade liberalisation,” he said.

He reminded that developing countries and advanced nations operate under different conditions and these variegated conditions can be stumbling blocks instead of building blocks to solidarity and cooperation.

These views are moot, of course.

However, a binding call among economists is that governments should protect and preserve their policy and fiscal space when it comes to multiparty trade agreements.

Even more so in the current landscape where the world is engulfed by a pandemic, and financial and climate change crises.

They warned that losses from tariff revenue due to trade liberalisation are permanent in developing countries unlike in developed nations as the former is not able to collect taxes, such as income tax and corporate tax.

“I think governments have to keep a steady source of revenue [because] the revenue from the citizens in terms of taxes would become very limited when you have more unemployment in the country,” said Dr Rashmi Banga, a senior economic affairs officer in the Unit on Economic Cooperation and Integration among Developing Countries of UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD. “This is why it is important to hold on to policy space and fiscal space, and [trade] tariffs give you that space.”

She was referring to the recent study by Boston University on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which revealed corroborating evidence to support the argument against multilateral FTAs.

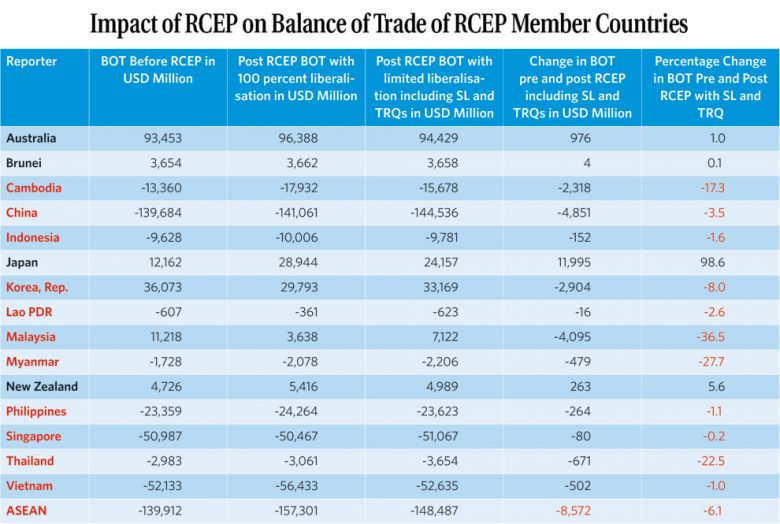

Using data derived from simulations incorporating sensitive lists and tariff rate quotas (TRQs) negotiated in the RCEP, final calculations, the study showed that non-ASEAN partners stood to gain more than bloc members.

A major portion of the findings rang true for Cambodia – which could experience even worse trade deficit by $2.3 billion per year – and for most of the ASEAN member states post-RCEP.

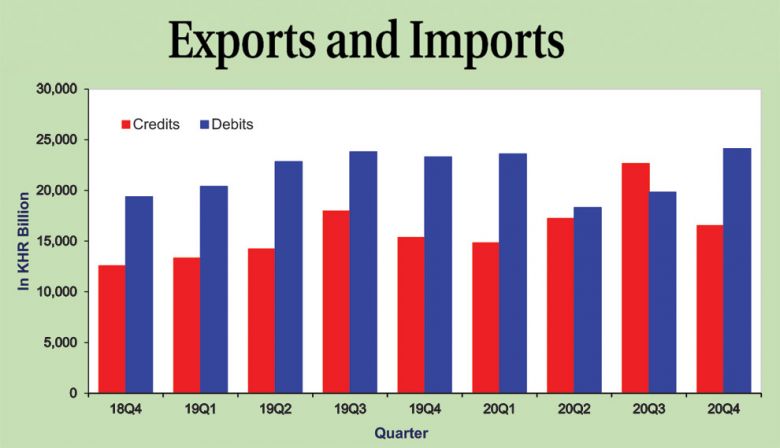

As it stands, Cambodia has been recording year-on-year trade deficit for over two decades, distinguished only by the quantum.

From the latest study, the maximum tariff revenue loss amounts to $334 million a year or 1.2 per cent of 2019 gross domestic product (GDP), which is significant for Cambodia as it is nearly the sum of healthcare expenditure, according to the World Bank.

“The lost revenue could have paid for around 150,000 nurses in Cambodia,” the study stated, based on International Labour Organisation calculations.

CGE’s unrealistic assumptions

Known as one of the largest trade pacts in the world, the RCEP was signed by ASEAN members and China, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand and Australia in November last year to increase market access, improve trade balance and in the case of the pandemic, to revive economic growth.

It should be noted that the chapters of the pact had been kept secret until the signing, although some of the text was leaked to the public over a period of time.

Last week, the Boston University study on the goods chapter alone showed that trade balance for ASEAN would fall 6.1 per cent to $148.5 billion.

Why is that? Because most of the RCEP countries have entered into FTAs, therefore, any additional market access among the countries would have to occur only if there was further trade liberalisation.

To date, the countries have already liberalised 80 to 90 per cent of their tariff lines. Thus, this would mean cutting through the sensitive lists, which includes tariff lines where no decision has been made to reduce tariffs or gradually reduce, as well as TRQs.

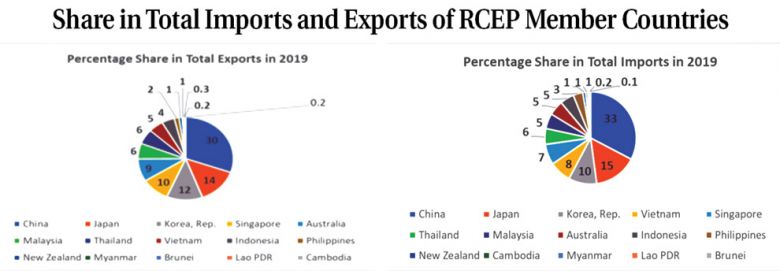

Based on the SMART simulations, a methodology developed by the World Bank and UNCTAD, and available on the World Integrated Trade Solutions, the maximum market access post-RCEP would see China, Korea and Japan gaining the most exports among non-ASEAN countries.

“Almost 88 per cent of market access is gone,” said Dr Rashmi in a webinar on the findings of the study last November.

As for imports, higher diversified imports are expected in all countries except ASEAN member states.

Conversely, Japan will enjoy nearly 100 per cent trade surplus at $24 billion.

In Cambodia, the figures are worrying as imports post-RCEP with sensitive lists and TRQs grow at 13.4 per cent or $2.3 billion.

A large amount of that would be supported by goods from China, at 79 per cent growth.

The top five imports for Cambodia with vast changes in import tariffs include clusters of knitted or crocheted fabrics (up 44 per cent), man-made stable fibres (13 per cent), nuclear reactors, boilers, machinery and mechanical appliances and parts thereof (eight per cent), cotton (four per cent) and vehicles of other railway or tramway rolling stock, and parts and accessories thereof (three per cent).

For instance, “other knitted or crocheted fabrics” will see a spike in import value at $786 million a year from RCEP countries. Of that, some $670 million a year is from China and $76 million from Malaysia.

In comparison, exports might only register a dip of 0.2 per cent or $8.5 million but as mentioned, it could experience further drop due to trade diversions in favour of more efficient exporters in the RCEP region.

The study was done by Dr Rashmi with Dr Kevin P Gallagher, professor of Global Development Policy at Boston University’s Pardee School of Global Studies and Prerna Sharma, an Australia-based consultant with UNCTAD.

The methodology enabled estimation of the impact of tariff reduction at a very disaggregated level, for example, obtaining data if tariffs on broken rice at harmonised system (HS) six-digit are removed.

According to Dr Rashmi, the disaggregated product-level estimations of the impact is not possible in any other model.

Often, policymakers use the computable general equilibrium (CGE) modelling to achieve convincing results.

However, it has been criticised for its “unrealistic assumptions” of perfect competition, full employment, balanced government budgets and unrealistic economic conditions.

“Any gains showed by CGE models in terms of changes in GDP of member countries and associated gains in terms of foreign direct investment (FDI) are overestimated since the increase in exports of member countries might not materialise if the products are in the sensitive lists and face TRQs of partner countries,” she said.

ERIA study includes India?

That being said, the Economic Research Institute of ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) used the CGE model simulations when conducting the feasibility study on benefits and impacts for RCEP member states.

The results, benchmarked at the 2007 global trade analysis project, indicated that Cambodia’s GDP would expand two per cent while exports and investments will extend further.

It worked on three policy scenarios over the simulation period from 2016 to 2030, where it contemplated tariff cuts of 50 per cent to 75 per cent, lowering of country specific risks by five basis points as well as the removal of trade barriers to service by seven percent.

Assuming investments increase based on 75 per cent tariff liberalisation, Cambodia’s real GDP would hover above five per cent in 2030.

In fact, among the RCEP countries, ERIA found that Cambodia stood out as its real GDP was larger than other ASEAN member states.

“The country has higher tariffs on imports used for forming physical capital, and liberalisation lowers the price of capital goods.

“Because of the fall in the price of capital goods, the large increase in investment in Cambodia contributes to the higher gain in real GDP,” the report shared by Ministry of Commerce undersecretary Penn Sovicheat, showed.

However, the report is from August 2015, according to ERIA’s website, which makes the figures unreliable because it includes calculations with India still in the picture.

Recall that India walked out of the negotiations in 2019 after internal studies showed that losses would outstrip its benefits, including the devastating outcome to its agriculture industry, on the back of dairy product importation from New Zealand.

With India’s withdrawal, the RCEP text would need to be recalibrated based on the latest tariff leberalisation schedule. Otherwise, it is simply about a hypothetical FTA, not the actual RCEP text, an analyst who declined being named opined.

In addition, the current RCEP text predates the pandemic, which has created a shift in global economy and procurement, as well as disruptions in trade and technology.

‘Parties can sue’

Earlier this week, Sovicheat told a local English daily that many RCEP provisions are voluntary or vaguely-worded, thus enabling Cambodia and others to find possible timeframes to refine the real opportunity to be competitive to effectively implement them.

He stressed that national interest is a priority in acceding to the level of commitment and obligations in the agreement, including a transitional period of 20 years.

The thing is, Cambodia has 1,236 products out of 9,558 products which keep tariffs on them for 20 years or permanently. “But, 8,322 products have no transition period or transition periods are shorter than 20 years before Cambodia’s import tariffs on them are removed,” the analyst said.

While agreeing that some provisions might be voluntary and vague, it is not the case in the goods chapter where it is mandatory for import tariffs to be removed or reduced if Cambodia ratifies RCEP. Failure to comply, could result in Cambodia being sued by another RCEP government, and there is a high likelihood of Cambodia losing.

“In turn, the other RCEP party can raise the tariffs on Cambodia’s exports until Cambodia complies with RCEP,” the analyst shared.

However, it is hoped that the opposing party exercises “due restraint”, given that Cambodia is a least developed country. “However, it does not prevent the other parties from suing Cambodia for failure to comply and penalising it if it loses,” the analyst commented.

‘Little David versus Goliaths’

Meanwhile, economist Dr Chheng Kimlong believed that the assessment done by ministry indicated lower losses compared to gains upon deeper economic integration because of increased investments and exports.

“More jobs will be created, technology and innovation will be enhanced, higher domestic tax from business and investment activities will outweigh tariff losses,” he told The Post.

Although Kimlong expected trade deficit to widen and foreign exchange losses in the short to medium term, a rigorous export promotion strategy can compensate the losses or improve trade balance.

“Along that line, Cambodia will need to aggressively deepen and diversify its fledgling yet growing industrial and service sectors while transitioning to a mature economy,” he added.

Separately, David Van, Platform Impact Co Ltd’s public-private partnership senior associate, understood why Cambodia would opt for FTAs and regional trade deals.

“[It] is [because they are seen] as a “hedging tool” for the economy in the long term, although regional trade agreements such as RCEP are known to only benefit primarily industrialised countries,” he said.

“We are but a little David combatting in an arena full of Goliaths. This might explain the possible daunting picture painted by the [Boston University] report on Cambodia,” Van opined.

Thus, he said, it is now left to the government to expedite accompanying measures to effectively implement the Industrial Development Policy, launched in 2015.

“[We should see] how it can ramp up manufacturing and carve out niche industries [despite] our limited capacity while cleverly scaling up outputs in those niche sectors,” he said, adding that no economy can grow significantly without industrial manufacturing. “[And] certainly not with only services and our narrow industrial base stuck for decades with low cost garment and footwear.”

Similarly, Dr Rashmi urged governments to be pragmatic in terms of regional integration and that regional value chains are important.

“When more countries enter the ASEAN space, the preferential access is lost as that access goes to more efficient producers and exporters,” she said, pointing out that many ASEAN countries cannot compete with China in terms of exports.

“But you must have strategic interventions with governments and [the] ASEAN industry to initiate these regional value chains. Just linking into global value chains or value chains of an advanced country is not going to give you that benefit.

“You must upgrade in the value chain and within the region as there is a lot of potential to initiate ASEAN’s own value chain and export globally,” Dr Rashmi added.

On that note, she reiterated that governments need to preserve its fiscal and policy space. For instance, tariffs can be unilaterally put down to zero without signing agreements or binding oneself to reduce tariffs.

“This is the [kind of] policy space we are talking about . . . if tomorrow you don’t want those products coming in [because] you want to build your sectors which are producing inputs you were importing earlier, you can raise tariffs on those inputs.

“[This way] you get to give some protection to your own domestic industry which is coming up in terms of providing inputs for your production,” Dr Rashmi explained, asserting that it should be done now. “I won’t say in the near future . . . I would say from today itself.”