CETA deal will open up new markets for Canadian beef

Manitoba Co-operator | 24 March 2016

CETA deal will open up new markets for Canadian beef

By Barb Glen

When John Masswohl toured the central London wholesale meat market in December, he found some Canadian beef for sale.

But not very much.

Five boxes of Prairie Heritage beef, from animals raised in Alberta and Saskatchewan, were on offer beside hundreds of boxes from the United States and entire pallets from Argentina, Uruguay and Australia.

“For every box of Canadian beef, he had at least 100 boxes from somewhere else,” said Masswohl, who is the director of government and international relations at the Canadian Cattlemen’s Association.

Marketers told him Canadian beef was expensive, in part due to tariffs. Technical issues also make it difficult to acquire.

That situation could change dramatically when the trade deal between Canada and the European Union, called the Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement, comes into force.

“We’ve got an outstanding quality product and an outstanding eating experience that goes with it, and I think for a price, that would be very comparable to what Europeans are used to paying if we didn’t have to deal with all these tariffs and other conditions,” said Masswohl.

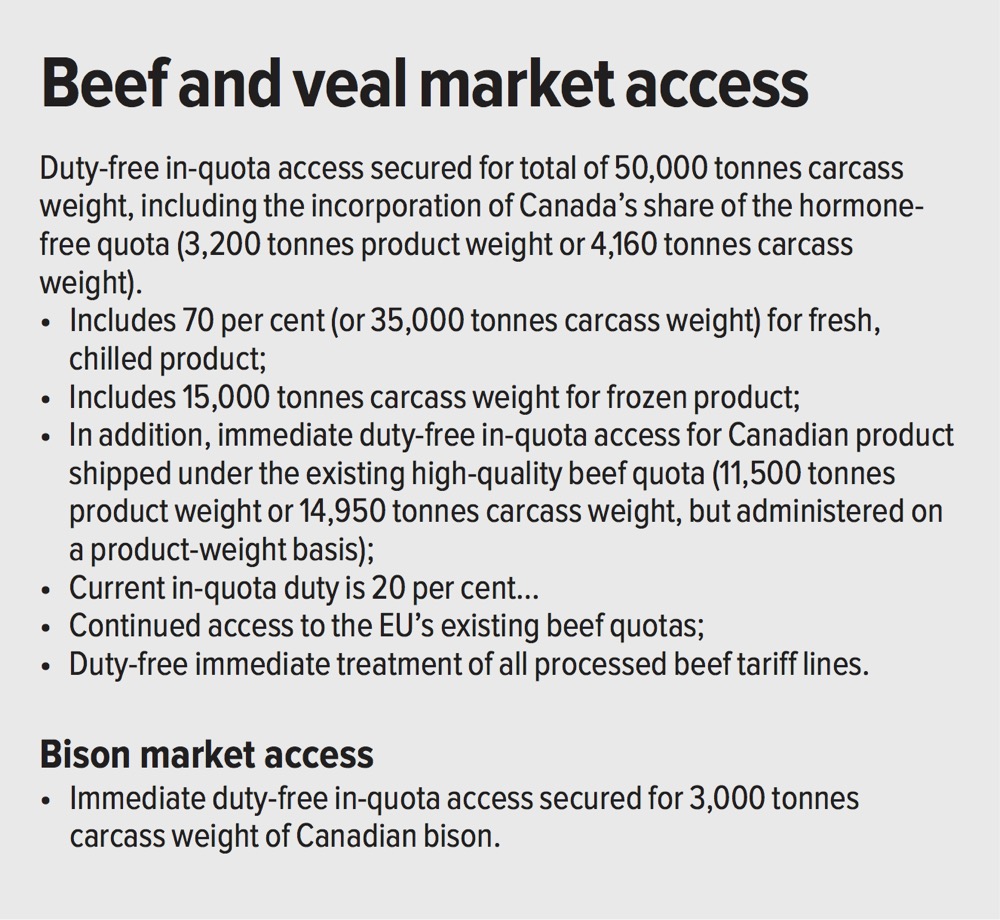

The deal will allow beef and veal exports worth an estimated $600 million, generated from 65,000 tonnes of new duty-free access to Europe. About 50,000 tonnes of that is in fresh beef and the balance in frozen product.

Using an estimate of 100 kilograms of fresh beef available per animal, it could translate into a market for 500,000 Canadian cattle, if they meet the EU requirement of being raised without the use of additional growth hormones.

“How many cattle do we have in Canada being produced according to EU standards, or could be if they were properly documented? I’d only be taking a guess,” said Masswohl, “but I think right now, today, somewhere less than 100,000 head. But with the incentive there, I’ve talked to lots of guys who say, ‘if the incentive is there, I’ll do it.’”

Not so sure

Feedlot owner Rick Paskal of Picture Butte, Alta., isn’t so sure the incentive will be enough to encourage more production of beef that meets EU specifications.

“They don’t recognize the science of the day, so we’ve got these free trade agreements with them, but it’s still just the same. We don’t meet their criteria for trade, which is not science based,” said Paskal.

“I don’t understand why we would have negotiated an agreement like this. It sounds like we’ve got an opportunity to put Canadian beef in Europe but we don’t and we never will.”

Paskal said use of growth hormones reduces beef production costs by about $250 per head through better feed conversion and shorter time to fatten. Price premiums offered in Europe for beef free of added hormones would have to cover that, and he thinks that is unlikely.

“It’s good that all the people around the world get talking to one another and they want to expedite trade and reduce trade barriers, but they’ve got to go back and… really, if there’s a spirit of trade, just address the science.

“It’s got nothing to do with food safety. We’re all big proponents of food safety, your product, your animal handling, the animal welfare aspects are very, very important. We’re not saying we’re ever going to circumvent them, but it’s got to be based on science.”

Opportunity

Doug Price, who runs Sunterra beef operations, said he sees opportunity through CETA for more beef exports but the price has to be right.

“We have the cows and the feedlots. I’ve got a pretty good handle on what it costs me to produce non-hormone, traceable cattle. It’s really easy for us to do that, but I need to know how much premium will I get for that before I do it,” he said.

Price suggested opportunities in Europe might better suit smaller, more nimble operations that can cater to higher-end niche markets.

“If we get some of our product over there, I think they’ll pay quite a premium for it. So I think the opportunity for sure is there. We just have to put all the pieces together,” said Price.

“Our genetics here in Canada and our technology inside the cow-calf right through to the feedlot to the plant is as good as anybody in the world and I think the genetics are even better. There’s less variability. So any kind of a quality market, man, we’re sitting real good there.”

Small scale

Producers involved in Prairie Heritage Beef have been meeting EU requirements and building their niche for years but on a relatively small scale.

Before selling the brand to One Earth Farms in October 2014, Prairie Heritage was selling beef from about 5,000 animals into Europe and another 5,000 domestically, said former president Cliff Drever of Camrose, Alta.

Christoph Weder, a cattle and bison producer in Hudson’s Hope, B.C., was the primary marketer for the branded beef line before its sale. In his view, Canadian producers won’t be able to fill the entire EU quota unless the two major packers in Western Canada, JBS and Cargill, develop separation of hormone-free and commercial beef.

He and others hold out hope that Harmony Beef, the former Rancher’s Beef processing plant in Balzac, Alta., that is expected to market specialty beef into Europe, will open soon. That would add to output provided by Canadian Premium Meats in Lacombe, another EU-approved plant.

However, Harmony Beef has been beset by water issues and various other objections put forward by the city of Calgary and has yet to start operation.

Producers with an eye to producing beef for Europe must meet specific requirements subject to Canadian Food Inspection Agency oversight.

Jason Hagel, a Three Hills, Alta. producer with Prairie Heritage, said those requirements might be enough to discourage greater production.

“I don’t think it will change much,” said Hagel.

“The program that Canada has in place is very onerous on producers to actually want to do it, with all the paperwork and CFIA vets having to come and make sure everything’s in place.

“Which we need, but it’s a lot easier just to take your cattle to market and sell them to a feedlot than going through a bunch of paperwork and having to keep track of the animals that you do send, have an inventory list and all that kind of stuff.”

Quotas and tariffs

Until CETA goes into effect, certain quotas and high tariffs remain in place so few producers are raising animals now with a view to the EU market.

“Right now it’s not worth it because you’re not getting any more money by doing that, as a cow-calf producer, than taking them to the market and just selling them in the open market,” said Hagel.

He said One Earth can’t afford to pay much more than the commodity market at present because any premium from Europe doesn’t cover the extra cost involved in producing the beef.

He also wonders if December’s repeal of country-of-origin labelling (COOL) in the United States, which used to discourage Canadian cattle sales across the 49th parallel, will prompt producers and packers to take that easier path.

“We have two American packing plants in Canada. They have pretty good connections in the States and can move the beef easier. They’re not going to chase after a market that has to change the way they do business in their own plants and cost a lot more.”

Not yet approved

And speaking of plants, the safety methods employed by Canada’s major packers have yet to meet the approval of the EU. That’s another hurdle that must be overcome before Canadian beef benefits from CETA.

These technical considerations are not part of the CETA agreement, but they exist in a side arrangement that says the two parties will work toward equivalence in their respective meat inspection systems.

That equivalence has yet to emerge, said Masswohl of the CCA.

“Our idea of equivalence means that we can do things our way. They can do things their way. Not everything needs to be harmonized but the end result, the outcome, is equivalent in that we both produce safe beef,” Masswohl said.

“What we’ve learned is Europe’s idea of equivalence is they want us to do it their way. But we’re not doing it their way. Our way is much safer.”

Canadian plants use various antimicrobial carcass washes and safety techniques after cattle are slaughtered to destroy E. coli and other bacteria. Europe does not use the same methods.

Their way

The big three plants in Canada process more than 90 per cent of the country’s beef. The volume of animals, the distance they travel and the weather all play a role in sanitary and phytosanitary considerations at the plants.

Europe, in contrast, has hundreds of slaughter facilities, many of them processing small numbers of animals delivered in small trucks from nearby locations.

“They say the animal needs to be clean before it comes into the slaughter facility,” said Masswohl. “So how does that work in our scenario where we have much colder temperatures to deal with for much longer periods of the year?

“The idea of washing animals outside when it’s below -20… it doesn’t seem like humane treatment for the animal. It seems impractical.”

Europe has agreed to the use of lactic acid as a sanitary measure and more recently approved the use of recycled hot water but approval will be needed for other safety-related treatments that have become standard in Canadian plants.

“They just don’t do any of that and they just can’t fathom doing anything else,” said Masswohl.

“We rather suspect that they like the system the way it is because it keeps imported beef out of their market. We rather suspect that that’s a big part of the motivation for the way they do it,” said Masswohl.

“If we don’t resolve this, then the (CETA) agreement is of very little value for the Canadian beef industry. If we do resolve it, it’s huge value for us. It’s worth working on.”