RCEP remains distant dream; India’s return to this free trade agreement not imminent

Financial Express - 18 November 2019

RCEP remains distant dream; India’s return to this free trade agreement not imminent

By: Banikinkar Pattanayak

In fact, to prevent such circumference, India’s existing free trade agreements (FTAs) with Asean, Japan and South Korea already link duty concession to a 35% value addition, according to analysts.

Senior government functionaries, including commerce and industry minister Piyush Goyal, have indicated post-Bangkok meet that India might reconsider its pullout from the Regional Comprehensive Partnership (RCEP) agreement if its “concerns are adequately addressed”, but that will be a hard act to follow by potential partners. It is learnt that India’s differences with others like China are too wide to be bridged soon, especially on the rules of origin (ROO) of imported products.

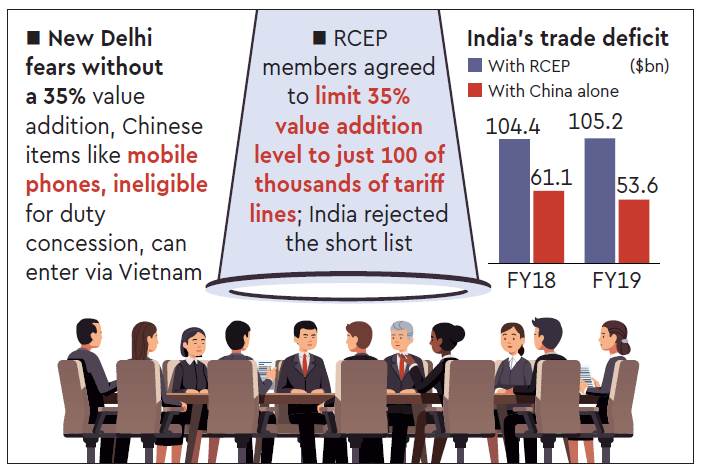

While New Delhi has pitched for “sufficient value addition” of at least 35% in the country of exports for a product to be eligible for its tariff concession under the RCEP, others want to settle for just minimal value addition. India strongly feels that in the absence of strict rules of origin, its different tariff concessions for different countries (the offers are least ambitious for China) and safeguard/anti-dumping tools against any irrational spike in imports will be rendered meaningless and exporters from certain countries can easily violate the spirit of the agreement.

For instance, a mobile phone that is excluded from the list of Chinese products eligible for duty concession in India can still land up here through Vietnam at a lower duty because the item is part of New Delhi’s offer list for Hanoi. This is despite the fact that the entire mobile phone is made in China but gets exported to India from Vietnam after the supplier adds, say, just tampered glass to it. “India’s condition for rules of origin would be among the most difficult proposals for countries like China to accede,” said one of the sources.

In fact, to prevent such circumference, India’s existing free trade agreements (FTAs) with Asean, Japan and South Korea already link duty concession to a 35% value addition, according to analysts.

“Upon India’s insistence on the 35% value addition clause in the RCEP agreement, other partners wanted to limit the list of tariff lines where such a level of value addition would be mandatory to just 100. India rejected such a short list. The main worry is about circumference of such exports from China,” said a source.

Safeguards for domestic industry, particularly, remain a crucial part of India’s negotiations at RCEP and New Delhi feels its efforts towards credible deterrence against “irrational spike in undesirable imports” can be easily thwarted by vested interests without tough rules of origin, said the source.

A day after India decided to pull out of the 16-nation Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) talks, commerce and industry minister Piyush Goyal on November 5 indicated that New Delhi might get back at the negotiating table only if its demands — including extra safeguard mechanism to curb irrational spike in imports and tougher rules on the origin of imported products — were adequately addressed. However, for now, the country had decided against joining the RCEP, he asserted. Although the 15 other nations went ahead with the pact in November, they showed willingness to accommodate India’s concerns.

A joint statement of RCEP nations after the November 4 summit in Bangkok, where Prime Minister Narendra Modi attended, was also silent on India’s decision to pull out. It merely said: “India has significant outstanding issues, which remain unresolved. All RCEP participating countries will work together to resolve these outstanding issues in a mutually satisfactory way. India’s final decision will depend on satisfactory resolution of these issues. “This was a clear indication that others were keeping the doors open for India to join back should it so decide.

After the pullout, Goyal said India was unwilling to budge on its core demands on an “auto-trigger” mechanism for safeguarding domestic industry from dumping, despite pressure from partners. Also, it was steadfast in demanding credible steps to address India’s $105-billion trade deficit with RCEP members, a more balanced deal on services, strict rules of origins of products to check the abuse of tariff concessions and change in the base year to implement the tariff abolition from 2014 to 2019. Moreover, it almost wanted its agriculture and dairy sector out of the RCEP negotiations.

Most members wanted to conclude the negotiations in 2019 so that a deal can be formally signed in 2020. A source had earlier said that India was planning to employ an “auto-trigger” safeguard mechanism for imports from not just China but also Australia and New Zealand to better protect domestic players from irrational spike in imports. However, the move was resisted.

To protect its industry, India had decided to trim or remove tariffs on Chinese goods only in phases over a period of 20-25 years. Similarly, its tariff concessions was to be the least ambitious for China—it offered to reduce or abolish import duties on a total of 80% of imports from China, against 86% from New Zealand and Australia, and 90% from Asean, Japan and South Korea.

Even without RCEP, India’s merchandise trade deficit with China stood at $53.6 billion in FY19, or nearly a third of its total deficit. Its deficit with potential RCEP members (including China) was as much as $105 billion in FY19.