Trade agreements are colonial tools to control lands, resources and labour, says Canadian activist Stefan Christoff

All the versions of this article: [English] [Español] [français]

Interview with Stefan Christoff

Stefan Christoff is a media maker, musician and community activist living in Tiohti:áke / Montréal. Find Stefan on Twitter @ spirodon.

by bileterals.org, 24 January 2022

Transcript (edited by bilaterals.org)

bilaterals.org: To what extent do you think Canada’s trade deals are a legacy of its colonial history?

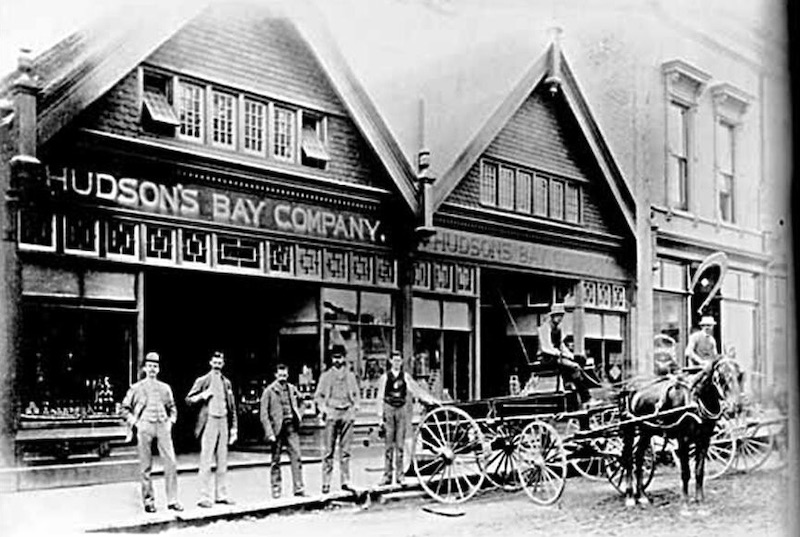

Stefan Christoff: It’s essential to locate Canadian economic policy within the history of this "country". Canada, as a project, foundationally is a Crown corporation, an extension of British imperial interests internationally. Hudson’s Bay Company was the foundation of Canada as an institution, which was rooted in dispossessing indigenous lands, territories, and resources. This is the origin point for Canadian economic policy. When we think about Canadian economic policy today, whether it’s through corporate sector initiatives or governmental trade agreements, they are profoundly shaped by this history. If we think back to the foundation, for example, of multilateral institutions like the G20, the Liberal Party, which is in power right now in Canada, was foundational to that process. And if we think of other initiatives, like the Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI), which was struck down, or the Free Trade Area of the Americas agreement, which was also struck down, both in response to social movement pressure, the Canadian government was central to both of those initiatives, in terms of the corporatisation of trade policy and investment policy globally. And although the tactics and political rhetoric are different than the United States, there is a very important configuration of political interests that are central to both projects, as colonial nation-states.

Why do you think then many still see Canada as a nice, progressive country, as opposed to the US that is supposed to be the bad guy, so to speak? You know, if we’re talking about perception, many people around the world see the US as very aggressive, as opposed to Canada. And even though, as you’ve mentioned, Canada has had a violent history as well.

Well, I think that there’s overt violence and then there is systemic violence that happens in a more subtle way, which is harder to track. So, if we’re thinking about the realities of economic policy, it’s an important window through which we can see the nature of the Canadian state and corporate apparatus. So, when we think about the juxtaposition of the United States and Canada, there have been examples where Canadian policy has differentiated itself from US policy, but often that is as a result of social movements on both sides of the border, shaping and contesting economic policies. Now, the origin point of social movements in Canada is indigenous resistance to colonialism. Over time, we saw also various forces take root within agricultural communities, workers, urban networks, the formation of labor unions. All those forces are much stronger than mainstream historical narratives give credit to. And a lot of social policies that the Canadian state claims in terms of the global image of Canada are a result of the struggle of these social movements over years. Indigenous people struggled for a lot of the environmental protection laws that exist in Canada, which the government is currently trying to strip away. Social institutions like health care, some labour rights that exist are a result of struggles of social movements over generations. So the government, after they’ve been forced in different examples to adopt policies that might seem progressive internationally, then plays and manipulates them to use for an image to sell corporate trade agreements globally. But those policies were never the initiative of the state. They were always the initiatives of social movements or anti-colonial movements that were contesting the original colonial economic violence that is foundational to Canada.

In that sense, you recently wrote about the renegotiation of the Canada-Israel free trade agreement (FTA). Do you see a strong link between Canada’s history and the history of Israel, in connection to the situation in Palestine?

Often when we think about movements for justice, human rights, ecology, we can have questions about the ways that those frameworks are co-opted by international institutions. Regarding human rights, particularly, there’s an important critique about the nature of who gives rights, who owns rights, who owns the rights framework. But as it stands, when we think about the reasons and the orientation of supporting human rights, for example, in Palestine, the focus of our opposition to the Canada-Israel free trade agreement shouldn’t revolve around this being an exception. It’s not just happenstance that this agreement took place. It was one of the first trade agreements that Canada signed. It was first signed in 1997. NAFTA was in 1994. Before that was the Canada-US trade agreement in 1988. The Canada-Israel free trade agreement is not an exception to policy, it’s about colonialism. And it’s about a similar economic framework that exists in both places. Although the economies of the Israeli colonial state and the Canadian colonial state are different, there is the manifest destiny framework that is foundational to both places: frontierism - this concept of the political imaginary shaped by expansion, innovation, this sort of buzzwords today. We need to think critically about that because, if we’re thinking about the celebration of the Israeli tech sector, we’ve seen the ramifications of what that means through the Pegasus spyware scandal. That’s just one example. I mean, there’s a whole plethora of tech organisations, companies connected to the Israeli state security establishment which are playing a role internationally.

Speaking of corporations, Canadian companies have also been quite aggressive throughout the world, in terms of investment, and the way they sue countries in arbitration courts, especially countries from the Global South. For me, this is also a direct legacy of the colonial history of Canada. The Canada-Israel FTA renegotiation is just another step further, right?

A trade agreement like the Canada-Israel FTA is to support those corporations. Specifically, that agreement is revolved around the tech sector and innovation. Innovation has been given this positive spin. But what does innovation mean if we’re talking about working with a government that backs corporations that are involved in projects like Pegasus spyware? There’s no accounting for this. If we think about the Canadian side of this trade agreement, it’s not an exception. So what I mean is that it is not surprising that the Canadian government wants to engage with the Israeli state in this trade agreement, given that the entire identity framework of Canada, politically and economically, is also rooted in innovative expansionism of a colonial framework. It’s rooted in Western European conceptions of time and history. The western parts of so-called Canada are still being contested - if we think about the Shuswap nation, the Wet’suwet’en nation, and many other indigenous communities who today still question the very essence and existence of the Canadian state. But it shows, I think, the vulnerabilities of the Canadian colonial project because, in a very essential way, the economy of Canada is rooted in the exploitation of natural resources of indigenous lands and, you know, huge sections of British Columbia. There is no treaty for those regions, right? So Canada is negotiating these international trade agreements without actually having a legal framework for its own existence over a lot of territories that it claims to be part of Canada. This is why Canada is so frightened by indigenous protests.

One particular example that I found interesting in your article is the fact that, in the Israel-Canada free trade agreement, there is no distinction between Israeli products that are produced in Israel and those coming from the settlements in Palestine. Is this something new that came up in the renegotiation?

No, unfortunately. The agreement never made any differentiation. If you look on the Canadian foreign affairs website, Canada doesn’t recognize the legitimacy of Israeli colonial settlements within occupied Palestine; I mean, obviously their violation of a whole bunch of international legal frameworks, the Geneva Convention being one of them. And so, there’s a contradiction in Canadian policy here, where foreign affairs articulate these settlements as illegal Israeli settlements and the economic production that happens within them. But the trade agreement doesn’t differentiate between what is produced in these colonial settlements and what is considered to be from Israel’s proper pre-1967 borders (which were established after the dispossession of Palestinians that happened in 1948 and before the occupation of the West Bank that happened in the 1967 war). The trade agreement itself is very questionable, and it shows a lot of the hypocrisy of the Canadian Liberal government. That’s sort of intentionality is important. Image is one thing, but process and legal specifics are another.

And Canada can manipulate its image to push other trade agreements, as it did for the European Union-Canada trade agreement (CETA).

The actual reality of the bilateral trade agreement with Israel, and how it violates human rights law and Canada’s own policy, is contradicted around that. It shapes a corporate vision and colonial vision that is central to Canadian trade policy. We can’t distinguish between Canada’s interests as a colonial force, and in terms of indigenous people within Canada, and how that’s manifested internationally with corporate trade agreements. When we look at the contemporary negotiations on other trade agreements, like those happening right now between Canada and the ASEAN area, and between Canada and Indonesia, we think about the role of mining corporations and industrial production. There’s violence there that is profound. These trade agreements facilitate corporate investment and push forward frameworks where labour rights, environmental protection are not respected. So these aren’t exceptions. These trade agreements are a manifestation of colonial policy internationally. And Canada’s government pushes this. The Canada-Israel trade agreement is just one example of this broader process of colonial expansionism that is at the origin point of the Canadian institution as a state because it started as a corporation.

In 2021, a letter from several Canadian movements and activists called for the end of the Israel-Canada free trade agreement. It’s actually quite hard to raise awareness on these issues among some movements. What do you think could be done to improve the understanding of trade-related issues?

Well, we have to locate and understand trade policy as a manifestation of broader political and economic interests. These policies are just basically a manifestation of the larger systems of violence that social movements are critiquing. They’re one mechanism. Bilaterals.org is an important resource because it tracks these trade agreements. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives in Canada tracks Canada’s negotiations of trade agreements, for example, and they do important work on this front. Even the UN special rapporteur on human rights in the occupied territories of the West Bank and Gaza, Michael Lynk, has written about and spoken about the Canada-Israel trade agreement, at the United Nations. What I’m trying to say is that the questions are very broad. But I think one thing that brings a lot of these points together is that we can’t decouple trade agreements from broader critiques of militarism, human rights violations, or environmental degradation. Trade agreements are the technical mechanisms through which colonial legal processes insert themselves to control territories, lands, resources, and labour. They are the mechanisms, the gears of that process. We need to understand that these systems of political control and colonial violence don’t just happen. There are mechanisms through which they’re manifested and trade agreements are essential in the mechanical workings of the colonial economic system.