Australia-US Free Trade Agreement - fair trade or foul?

Jemma Bailey

September 2007

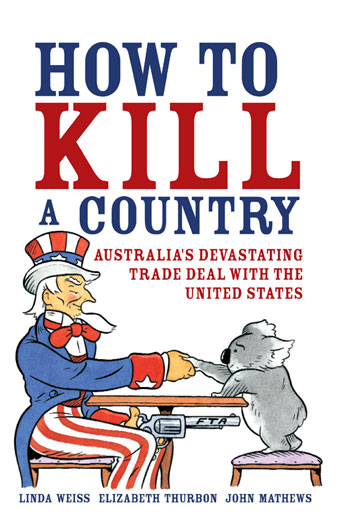

A lasting image from the campaign against the Australia-US Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA) is a cartoon that appeared on the cover of a book about the negotiations called “How to Kill a Country”.

The cartoon showed a koala (representing Australia) standing on a chair and craning its neck to see over the table. On the other side of the table sat Uncle Sam (the US), dressed in red, white and blue. Over the table, the koala and Uncle Sam are smiling and shaking hands. Under the table. Uncle Sam is holding a gun firmly against the koala’s belly.

In truth, the story of AUSFTA is not as simple as this. The political party in power in Australia during the negotiations — the conservative Liberal party — was very committed to free trade and far too keen to cosy up to the US. But as in most trade negotiations with the US, the Australian government was far from an equal bargaining partner. Ultimately a very bad deal for the Australian public was signed.

The AUSFTA campaign journey

AUSFTA negotiations began in March 2003. By February 2004, the deal was agreed and the final text — all 800 pages of it — brought out from behind closed doors.

The power imbalance in the negotiations was clear — the Australian economy is the size of only 4% of the US economy. Nevertheless, the Australian government went into negotiations with little more than a heartfelt commitment to free trade and neoliberalism, a false apprehension that the US would open up its agriculture markets and a misguided belief that the US was a “mate” who would look after it in the negotiations.

The Australian government, with the help of business lobbyists and the Rupert Murdoch media, furiously spun the worth of the agreement. Prime Minister John Howard described AUSFTA as “a coming together of the planets ... which won’t again happen in a generation or more”. For Parliamentary Secretary to the Trade Minister De-Anne Kelly, AUSFTA was the “world cup of trade”.

A strong community campaign opposed the undemocratic nature of the negotiations and demanded that health, social and environmental policies be excluded from AUSFTA. The final stages of the campaign mainly targeted the more progressive opposition party, the Australian Labor Party (ALP), in the hope that the ALP would block any changes to Australian law in parliament.

The deal went through parliament in August 2004. It passed after the more conservative faction within the ALP used its majority to force support for the agreement — albeit with amendments to penalise abuse of patents by drug companies and to maintain protections for current media forms.

The final deal was lopsided, to say the least. Australia’s most competitive exports, including fast ferries, stone fruit and wine, continue to be barred from entry into the USA or are very restricted. Sugar is entirely excluded from the agreement, and beef and dairy tariff reductions will be phased in over 18 years.

Lining up the targets - impacts of AUSFTA

In 2002, former US Trade Representative Robert Zoellick wrote to US Congress with a list of key social policies in Australia that the US had identified as burdensome “barriers to trade”. This letter was an important document that identified the key areas of the AUSFTA campaign.

• Affordable medicines - Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

US negotiators had identified Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) as a barrier to trade. Under the PBS, the Australian government bulk-buys approved medicines at wholesale prices to ensure that medicines remain affordable in Australia. Medicines in Australia are 3-10 times cheaper than in the US. Not surprisingly, big US pharmaceutical interests wanted AUSFTA to deliver greater rights for drug companies ... and of course, more expensive drugs.

Community campaigning saved most of the PBS. Small changes however, such as allowing the extension of patent periods for medicines, are likely to undermine the PBS and delay the availability of cheaper generic medicines.

• Labelling of genetically modified foods

As a result of consumer campaigns about the environmental and health impacts of genetically modified (GM) foods, Australian law requires them to be labelled. US negotiators wanted to weaken Australia’s laws, bringing them in line with the lax US labelling requirements.

A strong campaign by farmers and environment groups in Australia blocked US attempts to scrap the labelling system.

• Adopting US copyright law

The US sought to replace Australia’s copyright laws with US copyright law. The intellectual property chapter in AUSFTA is basically a cut-and-paste of US laws. Among other things, AUSFTA extends the lifetime of copyright from 50 to 70 years. Libraries and public education bodies campaigned strongly on this point, as it will mean higher costs for copying materials, even for educational purposes.

• Local content rules in media

Australian local content laws require a minimum number of hours be reserved for Australian-made material in film, television and radio. Local content laws support the local media industry and ensure that diverse Australian voices are heard. US media companies already dominate the local market, and without this requirement for local content the Australian media industry would struggle to survive.

The community campaign succeeded in keeping local content rules for existing forms of media but not for emerging or new media. This means that the Australian industry will lose its protection as technology in film, television and radio advances.

• Quarantine

Australia has fairly stringent quarantine laws, which the US identified as a barrier to trade. Australian wine, pork and chicken producers claimed that weakening quarantine laws would leave them vulnerable to outbreaks of US diseases, viruses and pests not found in Australia. After a strong public campaign, Australian quarantine laws were largely maintained.

• Limits on foreign investment

The Australian Foreign Investment Review Board reviews proposed investments by foreign companies in Australia. The US wanted to remove these controls to get access to our strategic industries, such as media, telecommunications, airlines and banking. The US succeeded in raising the threshold for review for investments from $50 million to $800 million.

• Regulation of services and investment

The US sought to change Australia’s laws such that US companies could not be treated any differently from Australian companies. The campaign focused on essential services. Some key public services, such as health, education and public broadcasting were specifically excluded from AUSFTA. Water, energy and public transport remain in the agreement, however.

• Tariffs in key manufacturing industries

Australia has maintained high tariffs in the textile, clothing and footwear industry and the car industry. The Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union argued that cutting tariffs through AUSFTA would effectively close down those sectors and mean over 130,000 job losses, mainly in regional communities.

• Investor-state disputes mechanism

The US wanted an investor-state disputes mechanism in AUSFTA. This would have allowed US companies to challenge some Australian laws on the basis that they were inconsistent with AUSFTA and harmful to company profits. This would have effectively tied the Australian government’s hands behind its back when it comes to making laws that could affect US companies. Under an investor-state disputes process, complaints would be heard by a panel of experts in an international tribunal, closed to the public.

A strong campaign against AUSFTA used examples from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) of companies challenging local laws. The campaign succeeded in keeping an investor-state disputes mechanism out of AUSFTA.

|

Pulling strings — the forces behind AUSFTA AUSFTA was a blatantly bad deal for Australia — opposed by the majority of people in Australia and questioned by mainstream economists. It is rumoured that even the government’s own trade bureaucrats recommended against signing the deal. So what compelled the Australian government sign on the dotted line? Ideology: The conservative Howard government was ideologically committed to neoliberalism. It seems that AUSFTA was a good means to lock in their agenda of deregulation and privatisation. Corporate lobbyists: A number of well-funded business lobby groups played a key role in pushing for AUSFTA. In particular:

The Australian government was also careful to compensate some of the important industries that lost out in AUSFTA. For example, sugar farmers received an adjustment package of A$444m. Buying silence, perhaps? The war: AUSFTA was negotiated in the shadow of the so-called war on terror and the Australian government’s support — without the mandate of the Australian people — for the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. AUSFTA became increasingly linked with Australia’s military interests. Having hitched Australia’s wagon so closely to the US in the Coalition of the Willing, Australia’s Prime Minister seemed unable to walk away from AUSFTA. |

The campaign

The campaign against AUSFTA brought together a diverse range of organisations and movements in Australia, including trade unions, faith-based groups, environmental groups, public health and education advocates, librarians, pensioners and students. Many of these groups had not worked together before — nor worked on trade issues before — and alliances were formed that have lasted beyond AUSFTA.

These groups came together mainly through the Australian Fair Trade and Investment Network (AFTINET). AFTINET coordinated many joint actions during the campaign.

So what did the campaign look like ...?

- Community education - A large focus for the campaign. At the start of the campaign, many people still didn’t understand what an FTA was, let alone why they should care about FTAs. There were public forums, public meetings and community stalls in all capital cities and many smaller towns. A number of popular education publications were produced, as well as cartoons and animations, highlighting different aspects of AUSFTA. Check out the animation on local media content produced by the Screen Producers Association of Australia: http://www.spaa.org.au/freetrade.html

- Mobilisation and movement-building - Stepping beyond education, the campaign sought to involve and activate people. Public rallies were held in most capital cities. Organisations held campaign and letter-writing workshops. There were day long teach-ins in Sydney and Melbourne and train-the-trainer education sessions on AUSFTA.

- Lobbying - AUSFTA was negotiated in the lead-up to a federal election in Australia, so the campaign also focused on lobbying politicians, especially politicians from the ALP and sympathetic minor parties. Thousands of letters and emails were sent to politicians during the campaign, and AFTINET coordinated people to visit and lobby their local politicians. The campaign forced two parliamentary inquiries, which received over 700 public submissions. At the local council level, motions were tabled against the AUSFTA.

- Media - The campaign attracted a lot of mainstream and community media attention. Media unions brought in high-profile actors (and struggling singers) such as Toni Collette and Russell Crowe to raise the profile of the campaign.

There was some joint campaigning between activists in the US and Australia. For example, the Australian Council of Trade Unions and the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organisations (AFL-CIO) issued a joint media statement, as did environment organisations. Unfortunately, most of this joint campaigning was through larger organisations, and not very sustained.

An important aspect of the campaign was research to debunk the government’s rhetoric that the AUSFTA would be great for the Australian economy. The government relied on research produced by the Centre for International Economics to claim that the FTA would generate US$2 billion in economic benefits after 10 years. The devil in the detail was that these studies assumed totally free trade in agriculture — which was never going to happen. Groups within the campaign commissioned their own studies which projected losses and undermined the government’s claims.

From little things big things grow - measuring success in the campaign

Despite the strength of the campaign, AUSFTA was signed. Some could say that we snatched defeat from the jaws of victory. But the campaign did succeed in creating a genuine shift in the public debate about free trade.

In Australian politics, free trade had become a sacred cow that could not be challenged. The accepted wisdom was that free trade would lead to greater wealth and prosperity for all. And the ALP sang from the same songsheet as the conservative Liberal Government on this point.

The AUSFTA campaign sparked the biggest debate that Australia had seen on a trade agreement. The debate in the community — and even in the mainstream media — questioned whether free trade agreements were about making trade more open or whether they were about securing rights for large corporations and undermining public control in social policy.

The campaign shifted public opinion. At the start of the campaign, support for AUSFTA stood at 65%; by the time AUSFTA was signed, support had dropped to 35%. Even though AUSFTA was signed, it is universally acknowledged in Australia as a bad deal.

The campaign also succeeded in making a bad deal less bad than it would have otherwise been. There was no investor-state disputes process, and Australia’s quarantine laws remained relatively intact, as did laws on the labelling of genetically engineered foods. Local content rules for current forms of media were maintained and existing limits of foreign investment in Qantas, Telstra and media ownership maintained.

In the key area of medicines, the campaign pushed the ALP to force an amendment to safeguard Australia’s medicines policy against the practice of “evergreening” by drug companies. Evergreening describes the practice of drug companies lodging bogus patent claims to delay the marketing of cheaper generic drugs after patents have expired.

The sting in the tail is that in areas where the US did not achieve its goals, the US moved to set up joint Australia-US committees to allow for ongoing and unaccountable input into Australia’s policy making.

AUSFTA set up joint committees in medicines, quarantine and technical standards including food labelling. Three years on, we are still not able to find out who sits on these committees, when they meet and what they discuss.

|

The campaign continues ... AUSFTA came into effect on 1 January 2005. Almost three years into its operation, the impacts are becoming evident. Despite promises of economic riches, Australia’s trade balance with the US has declined by 32% — a deterioration of $3.3 billion. The Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union estimates that over 10,000 jobs have been lost as a result of the agreement. Not surprisingly, the Australian government has refused to conduct any public review of AUSFTA. Instead the government trots out a handful of individual success stories. Apparently an Australian pie company is doing well. Community groups and academics continue to monitor and highlight the impacts of AUSFTA and there have been some small wins along the way. For example, AUSFTA opened the door for US firms to tender for blood supply contracts. In 2007, community campaigning pushed state governments to reject the federal government’s attempt to push this through. AUSFTA allows for either country to pull out of the agreement with only 6 months notice. The campaign against AUSFTA continues. |

The koala and the gun in perspective

It is important to put AUSFTA in the context of other Australian trade negotiations. The Australian government, despite being the koala with the gun to its belly in AUSFTA, is far from innocent. A quick look at Australia’s trade negotiations with Thailand and Pacific countries show that the Australian government is itself quite adept at holding the gun under the table and negotiating its own trade agreements that push harmful neoliberal policies.

The challenge that remains for the movement in Australia is to harness the momentum of the AUSFTA campaign to hold the Australian government accountable for playing the role of the bully with other countries.

Resources:

- Australian Fair Trade and Investment Network (www.aftinet.org.au).

AFTINET brought together over 80 organisations during the AUSFTA campaign. This site has a great archive of campaign bulletins. For more detail about the impacts of AUSFTA, check out the AFTINET “10 devils in the detail” leaflet.

- Global Trade Watch Australia (http://tradewatchoz.org/)

This site has a comprehensive record of media from AUSFTA campaign.

- Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union

AMWU’s "Say No to USFTA" campaign (http://www.amwu.asn.au/default.asp?Action=Category&id=68)

- Friends of the Earth Australia

AUSFTA campaign page (http://www.foe.org.au/trade/learning-resources/australia-2013-united-states-free-trade-agreement/)

- Pat Ranald, “The Australia-US Free Trade Agreement: a contest of interests”, Journal of Australian Political Economy, No. 57, June 2006. (www.jape.org)

Good discussion of social and corporate forces for and against AUSFTA.

- An Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of the US Free Trade Agreement (http://www.OzProspect.org)

- ABC radio interview on impact of AUSFTA two years on with John Matthews, co-author of the book How to Kill a Country (http://bilaterals.org/article.php3?id_article=7828)

- Joint statement from Australian groups calling on the Australian Senate to block the AUSFTA legislation (http://aftinet.org.au/campaigns/US_FTA/usftasignonstatement.html)