Livemint | Mon, Oct 08 2012

A bilateral agreement in limbo

Signed with much fanfare, an Indo-Bangladesh deal on further trade between two countries is yet to take off

Biswajit Dhar

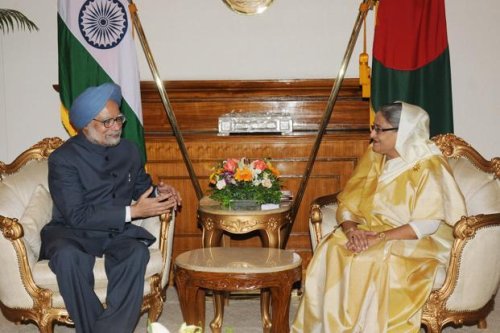

Just over a year back, the Prime Ministers of India and Bangladesh signed the framework agreement on cooperation for development, which was universally regarded as a milestone in the relations between the two countries. The agreement provided the basis for an extensive engagement between the two countries for mutual benefit.

A year has passed since then. There has been virtually no movement in implementing various parts of the agreement, which is important for strengthening bilateral economic relations. Given the substantial gains waiting to be reaped, it is imperative that the two governments draw up a roadmap for securing these gains.

India’s offer to give Bangladesh duty free and quota free market access to all the products that are of interest for the latter’s export basket was regarded as the most important step forward in strengthening the trade ties between the two countries. For reasons that are only of historical relevance, India had included a large number of products in its sensitive list for the least developed countries in South Asia. These products were thus denied the preferential tariffs that India had offered under the South Asian Free Trade Agreement.

What was most disturbing for Bangladesh was that this list of sensitive products included garments, the sector on which it has been heavily dependent for its export earnings. With India denying preferential access to garments, these products were virtually non-existent from its list of products imported from Bangladesh. Not surprisingly, therefore, Bangladesh faced a trade imbalance with India, something that has increased over time. India has faced constant criticism on this score.

While India should take some blame for this distorted trade structure, it has to be pointed out that Bangladesh imports from India products that are then processed to form a part of its country’s export basket. Cotton and man-made staple fibres and filaments have constituted one-third of India’s exports to Bangladesh. In other words, the contribution that India has been making to Bangladesh’s exports of garments cannot be underestimated.

Bangladesh’s exports to India provide another positive facet, which is that it provides an opportunity to the country to diversify its exports. Most of the items figuring in India’s import basket are, in fact, non-traditional items. That these are getting an opportunity for export in Indian markets means that Bangladesh’s export base is getting a chance to expand.

It is in this Bangladeshi effort to expand its export base to which India can lend its support. Producers of several non-traditional items face supply-side bottlenecks, a problem that can be addressed by Indian enterprises through establishment of joint ventures in Bangladesh. In the past, Indian firms have shown interest in large investment projects in Bangladesh, some of which failed because of the internal political dynamics in that country. Some of these failures involved large investment projects and in their aftermath, potential investors turned their back on the neighbour.

One strategy that can be fruitfully employed is to harness the potential of the small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Bangladesh. India will do well to contribute to this by providing the opportunities to link Bangladeshi SMEs to resources and markets in India. The food processing sector presents itself as an ideal candidate for the establishment of value chains between the two neighbours. Through a strengthening of this sector in Bangladesh, India can export the abundant horticulture products available in its north-eastern states. These states can then provide the necessary market to the producers in Bangladesh. What this example shows is that there are opportunities through which the resources available in India’s east and the north-eastern states can be matched with those available in Bangladesh in order to create a sub-region of prosperity.

Alongside preparing the blueprint for such production networks, governments and industry in both countries have to work in unison to ensure that obstacles to trade and investment are removed. Enterprises in the two countries have often complained of procedures and policies in their respective countries that hamper and even inhibit their operations, and the governments would have to invest adequate resources to ensure that these barriers are removed.

In this context, one area where India must focus on is the upgrading of the facilities available at the land customs stations (LCS) existing between the two countries. At present, most of these LCS provide only rudimentary facilities for conducting trade, with many essential services yet not available. Programmes were initiated during the 11th five-year Plan period for modernizing several of these LCS and converting them into integrated check posts (ICP), which would provide in a single modern complex, customs facilities, banks, food testing laboratories, all equipped with state of the art amenities for the conduct of trade. Under these programmes, seven LCS between India and Bangladesh are to be converted into ICPs in a two-phase programme. Setting up of these ICPs will not only provide greater opportunities for trade and commerce, but will also help in the development of the border regions, which are among the least developed in both countries.

Biswajit Dhar is director general at Research and Information System for Developing Countries, New Delhi.