The Tyee | 10 December 2019

How the ‘New NAFTA’ will affect Canadians

by Scott Sinclair

Scott Sinclair is senior trade researcher at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

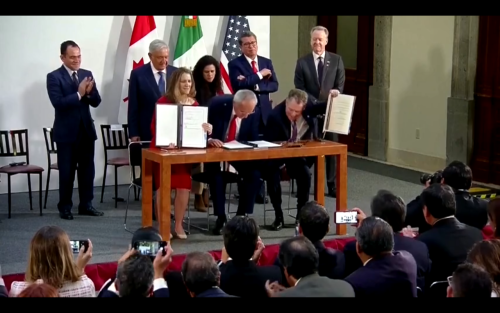

After months of talks, House Democrats and the Trump administration have agreed on revisions to the Canada–U.S.–Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) that will likely clear the way for U.S. congressional approval.

Although Canada was sidelined in these discussions, the Democrats won some significant improvements to the “New NAFTA” that will benefit Canadians.

The biggest change is the removal of proposed longer data protection periods for biologic medicines, such as treatments for Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis.

Data protection periods refer to the time competitors are denied access to the clinical trials data used to secure regulatory approval for a drug. Generic drug firms need this information to produce cheaper versions, known as biosimilars.

Currently, data protection periods for biologics are set at 12 years in the United States. Congressional Democrats, hoping to roll back that long period of monopoly protection for brand-name biologics makers, had no interest in locking minimum 10-year terms in place, as CUSMA would have done.

Under the original agreement, Canada had to increase its data protection term for biologics from eight to 10 years — at an estimated cost of at least $169 million per year, according to the Parliamentary Budget Officer. That change was dropped from the agreement, and Canadians will now avoid these projected cost increases.

Democrats have won other improvements, including curbing the practice of evergreening, where companies can obtain new patents based on small changes to existing drugs, blocking generic competitors.

One of the biggest sticking points in closing a deal was stricter enforcement of labour standards, with Mexico as the principal target. Democrats initially pushed for independent inspection of workplaces suspected of violating labour standards and the ability to withdraw preferential treatment of shipments from those factories under CUSMA if violations were found.

Mexican employer groups vehemently objected. Mexican President Manuel Lopez Obrador also rebuffed the demand as an infringement on Mexican sovereignty.

In practice, such inspections are a regular feature of international trade. Canadian and U.S. regulators, for example, routinely inspect foreign food facilities to ensure they comply with food safety standards. If they don’t pass muster, exports from those facilities can be suspended.

In the end, a compromise was reached with Mexico where complaints about workplaces can be heard by panels of independent labour experts and confirmed violations can lead to penalties.

In another positive change to the CUSMA labour chapter, the three countries agreed to loosen the condition that labour abuses be “sustained or recurring” to trigger sanctions, a significant hurdle that has allowed single violations of labour rights, however atrocious, to go unpunished.

These changes and tougher rules protecting Mexican workers’ rights to bargain collectively are an improvement over previous free trade agreements. But they won’t soon close the large manufacturing wage gap with Mexico or halt outsourcing. Indeed, just as a draft version of CUSMA was signed a year ago, General Motors announced plans to shutter five plants in the U.S. and Canada.

In the important auto sector, the U.S. pushed for tougher rules of origin if manufacturers are to qualify for tariff-free treatment under the agreement. Any steel used in auto manufacturing must be “melted and poured” within the NAFTA trade zone. This could be a boon to U.S. and Canadian steel producers.*

It is also possible some auto companies who use offshore steel will simply choose to pay the already low 2.5-per-cent tariff to export to the U.S. Nonetheless, Mexico objected and the steel rules will now be phased in over five years.

Democrats achieved scant progress on environmental protection. On a positive note, certain multilateral environmental agreements, such as the Basel convention on transboundary waste, will prevail in the event of any inconsistency with CUSMA’s rules.

However, the Paris climate agreement, which Trump confirmed the U.S. would be leaving on Nov. 4, 2020, is not among them. U.S. environmental groups are certain to strongly oppose ratification of a trade deal that ignores the threat of climate change and intensifies ecologically unsustainable trade and energy flows.

The Democrats have likely improved CUSMA for workers and consumers in all three countries. That doesn’t mean it’s the right deal.

The agreement, like the original NAFTA, privileges multinational capital and increased trade flows above all else. It weakens environmental policy by insisting it not interfere with trade or impose higher regulatory costs on business. It will sustain the accumulation of wealth in fewer and fewer hands.

Canadians can be thankful the new CUSMA will not result in higher prescription drug costs. We can feel relief that Mexican workers get a chance to form authentic trade unions and to fight to improve their wages and working conditions.

But we should take no solace in the fact politicians and governments have invested so much time and energy in salvaging a discredited trade model as they dither and delay on the climate emergency.