Even after years of TTIP talks, new study still unable to point to any major benefits

Ars Technica | 29 January 2016

Even after years of TTIP talks, new study still unable to point to any major benefits

by Glyn Moody

Last year, Ars provided an extensive introduction to the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) agreement currently being negotiated between the EU and the US. This massive deal—it involves half the world’s GDP and a third of its trade—was launched back in 2013, largely on the basis that it would provide a significant fillip to both economies. The previous EU commissioner responsible for trade, Karel de Gucht, claimed it would be “the cheapest stimulus package you can imagine.” A study published in 2013 by the London-based Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) on behalf of the European Commission predicted that the EU’s economy would be boosted by €119 billion, and the US’s by €95 billion.

However, it soon emerged that those figures were for an "ambitious" outcome—effectively, the best-case scenario; they also referred to 2027, after TTIP had been in place for ten years. The extra 0.5 percent boost for the EU’s economy predicted by CEPR worked out at only 0.05 percent extra GDP growth per year—a figure so small that it is likely to be swamped not just by the vagaries of econometric modelling, but also by major unforeseen future events in the global economy.

Once it became clear that the CEPR study offered no clear justification for pursuing TTIP, the European Commission quietly stopped using it, and moved on to purely anecdotal stories about how great the agreement would be for EU companies. Since it needed to drum up political support for the deal, that’s understandable.

What’s less comprehensible however, given the wide-ranging impact that TTIP will have on half the world’s economic activity and some 800 million humans, is that there have been relatively few detailed studies since the 2013 CEPR report.

That makes a major new report (188 pages!) entitled "TTIP and the EU Member States: An assessment of the economic impact of an ambitious Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership at the EU Member State level" particularly welcome. It was sponsored by the American Chamber of Commerce to the EU (AmCham EU), and "brings together the expertise of prominent academics from across Europe," as the foreword puts it. It consists of two main strands: a country-by-country guide to "the current situation and expected benefits" for each of the EU’s 28 member states, together with chapters that look at key aspects of TTIP as a whole.

The introduction to the key findings provides the following information about how the modelling was carried out:

To calculate our findings, we use a methodology that extends and enhances the most reliable approach to-date: Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) modelling. Utilising the ambitious scenario from the CEPR study ... we assume a 100 percent mutual reduction in tariff rates between the EU and US, a 25 percent reduction (on average) in regulatory divergences and behind-the-border non-tariff measures (NTMs) (i.e. assuming that over a 10-15 year period the US could move one quarter towards the level of the EU Internal Market), as well as a 50 percent reduction in barriers to procurement.

As that explains, the new AmCham EU report uses the same assumptions and the same model as the 2013 CEPR report mentioned above. So it comes as no real surprise that the predicted boosts to the EU and US economies are exactly the same: €119 billion for the former, and €95 billion for the latter.

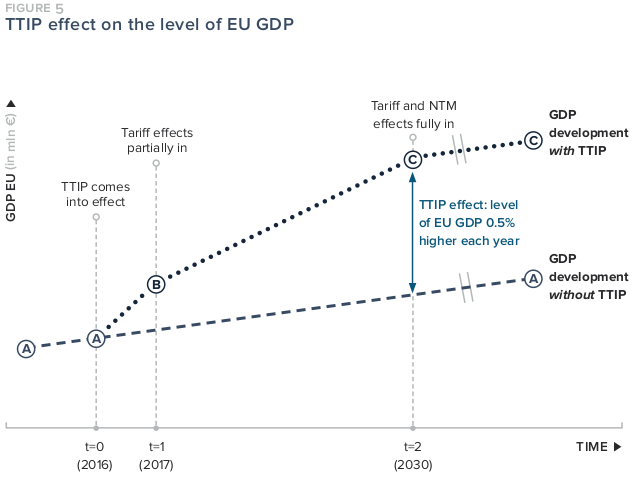

The percentage boost to the EU’s GDP is naturally also exactly the same as CEPR’s figure: 0.5 percent. That’s in 2030, so the time-scale has now lengthened from CEPR’s ten years to 14 years. Nothing wrong with that, of course, although it does mean that the average additional GDP per year is now even less—around 0.035 percent annual boost—as a result of TTIP. The report shows this graphically as follows:

This is not how you show extra growth of 0.5% in 2030.

American Chamber of Commerce to the EU

As you may have noticed, the diagram is rather misleading, since it plainly suggests that GDP in 2030 with TTIP will be around double what it would have been without TTIP, whereas it would actually only be 1.05 times greater in 2030—somewhat different. [Looks like someone needs to read Edward Tufte’s book-Ed]

A problem with the figures

The report then goes on to discuss exports: "one constant is that for all Member States, exports are expected to increase. The range of estimated export increases ranges from Slovakia’s +116 percent and Austria’s +64 percent, to Croatia’s +9 percent and Cyprus’ +5 percent." For the UK, it would be +17 percent.

There’s just one little problem with those figures. One of the core assumptions of the "Computable General Equilibrium" (CGE) modelling employed by both the earlier CEPR paper and this new AmCham EU report is that any increase in exports is exactly matched by a corresponding increase in imports. So while it may be great news that exports are predicted to surge across the EU as a result of TTIP, it’s important to remember that there is a corresponding surge in imports too. Strangely, the AmCham EU report doesn’t discuss imports.

That’s not the only peculiarity of the CGE approach. As well as assuming that exports and imports balance out, it also assumes that there will be zero change in overall employment as a result of TTIP. That seems slightly unrealistic, to say the least. But it does explain why the new study is also silent about the effects of TTIP on employment levels.

So far, the AmCham EU report has mirrored CEPR’s work, both in terms of its results and its problems—one of which is that neither report considers the costs of TTIP, only the benefits.

But things have changed since 2013, when CEPR’s report was released. We now know that there are elements of TTIP that present considerable risks, both economic and social. The authors of the latest study are naturally aware of that fact, and therefore have put together several chapters seeking to address those concerns.

Companies suing nations

Here, for example, is how it describes the 2014 consultation that the European Commission held on the subject of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS)—the mechanism that allows companies to sue countries over regulations and laws that the former feel diminish their future profits: "Reactions from the public were overwhelming; the Commission received around 150,000 replies. Although around 97 percent of the replies were submitted through automatic on-line platforms of interest groups, containing pre-defined negative answers, the European Commission was able to identify the following four topics on which further discussion was necessary..."

Here, the "negative answers" are portrayed as little more than some tiresome nuisance that the European Commission bravely dealt with as it struggled to come up with those four topics, all of which completely ignored the key point: that 145,000 people said they did not want ISDS in any form. But there is no discussion of that fact in the new study.

Moreover, it’s striking that the report’s chapter on ISDS does not offer a single reason why ISDS is needed in an agreement between two economic blocs with advanced legal systems. Indeed, in its endeavour to emphasise the fact that the EU and the US are already tightly linked economically, the report itself demonstrates that transatlantic businesses are already investing on a massive scale even without ISDS: "The EU-US relationship is particularly strong in terms of investments. The EU and US are by far each other’s main investment markets.... Finland, Sweden and Germany send over 40 percent of their investments to the US. Meanwhile, over half of investments into Luxembourg and the UK come from the US. These services and investment links form a core strength of the transatlantic economy."

And for those companies that might still want some protection before investing across the Atlantic, they can simply take out investment insurance just like members of the public are expected to do if they want to cover possible losses. However, there is no mention of this important alternative to ISDS in the AmCham EU report.

Regulatory cooperation

The other key area of concern in TTIP is over regulatory cooperation. Fully 80 percent of the already small GDP boost is assumed to come from the removal of "non-tariff barriers"—the different ways of doing things which make it hard for a company to sell exactly the same product on both sides of the Atlantic. But these "barriers" also include things like regulations that protect the environment or the online privacy of Europeans. A failure to remove enough barriers—possibly including those that protect the public—will mean that the gains from TTIP will be even smaller than the annual 0.035 percent predicted in the best-case scenario.

The report’s suggestions for facilitating removal include "a supporting body ... sufficiently resourced to support cooperation, to compare regulatory work programmes and identify new areas of cooperation, set the agenda, steer the process, share best practices, and solve issues as they arise," and "transparency and opportunities for stakeholders to give useful and robust input."

But as Ars noted recently, it is precisely these kind of corporate-friendly approaches, currently conducted on an informal basis, that have already delayed regulatory action or led to weak laws. Formalising them in TTIP will only exacerbate these serious problems, and further undermine national sovereignty.

Despite these faults, the new study is valuable for its detailed analysis of how each of the EU’s member states is likely to be affected by TTIP. It is also important for confirming that even in the most optimistic of assessments, an "ambitious" agreement will still produce vanishingly small economic gains for both the EU and US.

Finally, it’s striking how the AmCham EU report’s results are identical to those of the 2013 CEPR study. It’s almost as if, despite two and a half years of discussions, TTIP has gone nowhere. If nothing else, the new study exposes the awkward fact that repeated rounds of negotiations between the EU and US have failed to achieve any breakthrough in terms of turning TTIP into an endeavour with clear and quantifiable benefits, rather than one chiefly characterised by its serious and open-ended risks.