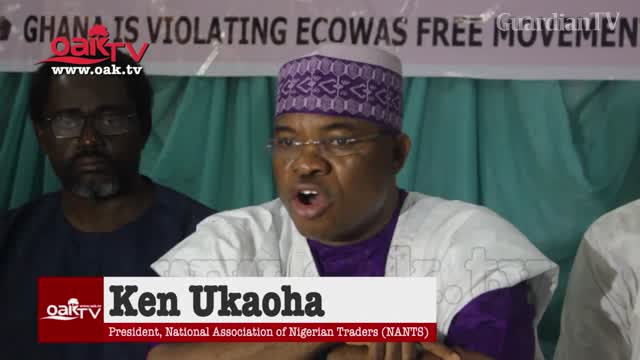

Interview with Ken Ukaoha

All the versions of this article: [English] [français]

2 May 2019

Interview with Ken Ukaoha

Ken Ukaoha is the president of the National Association of Nigerian Traders (NANTS) and shares his view on the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)

by bilaterals.org

bilaterals.org: 22 countries have ratified the African free-trade agreement, which is the minimum requirement for the entry into force of the treaty. What do you make of all the euphoria around this trade agreement, this African continental free-trade area (AfCFTA)?

Ken Ukaoah: For me, it’s a very good thing on paper. Especially when it comes to the objective, it is a very good one, if Africans can come together and trade together as a continent. So for me, it will lift up the trade volume, especially intra-regional trade and it will also go a long way to achieving some level of wealth creation arising from increased productivity. And moreover, such increased productivity would also reduce the poverty level. So that’s my idea. That’s my thought.

NANTS has been quite critical towards this deal and especially there have been some statements and reports saying for example that this African trade area will have a negative impact on farmers, for example, that it will increase unemployment among farmers in Nigeria and that it will be bad for the Nigerian industry, for small and medium enterprises. Could you elaborate on that?

K.U.: Yes for us, one of the reasons why we are criticizing is because we did not see the right things that needed to be done. It is on the basis of the fact that Nigeria, as well as other countries in Africa, did not conduct cost-and-benefit analysis of the AfCFTA to make it very categorically clear who are going to benefit, who are going to lose, and which sectors are going to benefit and which sectors are going to lose? What level of jobs will be lost? And what’s the level of wealth creation as well? And then we can use that, imagining the level of poverty reduction that it would bring in. And then, in terms of aggregating trade and productivity level, this analysis should have helped us to understand the overall impact and adapt the economy. But that was not done. So literally, because of that, we advised our President not to sign onto the AfCFTA framework. So until this moment, the President accepted that he will not sign until the writing was done. And of course, it resulted in consultations, embarked upon by the Ministries, by the government, with the stakeholders. Those consultations are now happening, and in fact, the result of the consultation is that the president set up a presidential steering committee to look at the impact and readiness of Nigeria on the AfCFTA. So the committee is working right now and I am privileged to be a member. It is because of what we are seeing the technical angles, that my organization now on that took this particular analysis on the impacts of the AfCFTA, potential impact rather, of the AfCFTA on agriculture. So that is exactly where we are right now.

Let’s speculate for a second. Let’s say for instance that a highly competitive Chinese or European company operates from Ghana and then has access to a free market because of this free trade area and they can compete with African local industries or companies that are not as competitive. Does it seem like a feasible scenario to you? Or, in other words, do you think foreign companies have a lot to gain from this free trade agreement?

K.U.: These are some of the things that we needed to consider and I think the negotiators are not looking at it properly. For instance, the scenario you painted - a Chinese company or a European company relocates to Ghana, or relocates to Nigeria, and once export from there to other African countries. Now, in the rules, do they qualify as originating companies? And do their goods qualify as originating goods? That’s one. Number two is what level of employments are they going to create? And is the framework allowing that? Now, if you also look at the subject of foreign direct investment. Would that be categorized as foreign direct investment? To what extent is the ownership of such companies that have located - those factories that have located? Or are there not going to be transshipping, you know, moving finished goods or semi-finished goods from China or from elsewhere, and they move into their company and using their company as a conduit pipe to export into other African countries and capture an African market? These are things that we are looking at and to what extent would that now impact on the economies of people.

Some critics based in Africa including, some economists actually, say that most African economies are based on exploitation of raw materials like natural resources and some claim that with this free trade area, African countries will simply exchange goods, semi-finished goods coming from abroad. Do you think they have a point there?

K.U.: Honestly, for me, I am not comfortable with such kind of “foreign direct investment”. What I feel should be the fulcrum or the objective of the AfCFTA, which will add value to the economy, is a relocation of such factories, number one. And the change in nomenclature in terms of ownership, practical ownership, so that these are owned by the people, by Africans, that’s number two. Number three is that the products coming out from these factories are wholly produced goods, fully produced goods, not transshipped goods, not semi-finished goods, not CKDs (Completely Knocked Down) products. But fully refined and produced goods that are owned by Africans, that are owned by the continent and then moving around the continent. This is the only way we can think about technology transfer. It’s the only way we can talk about sustainability. This is the only way we can talk about self-sufficiency. And this is the only way we can also compete favorably with other parties in the global economy. That’s my thinking.

And do you think that’s possible under the current form of the agreement? Because, for example, the rules of origins haven’t been determined yet.

K.U.: Exactly! The rules of origin would be a determining factor. A lot of work depends on the kind of rules of origin that we apply in this trade agreement. And of course, that’s why I was also insisting that our president should not sign on to a framework agreement that does not have full-fledged protocols that are attached thereto. For instance, the rules of origin protocol should be very clear so that everybody will understand, everybody will admit and accept what the rules of origins are. And then it should be attached to whatever any president is signing, any country is signing. So it becomes a working document. Not the other way around - signing an agreement and then coming back to negotiate rules of origin. Supposing you come up with the rules of origin that’s not acceptable to a country, what happens? That country would have signed already a framework. That’s the wrong model.