Learnings from the struggles

Todas las versiones de este artículo: [English] [Español] [français]

Learnings from the struggles

bilaterals.org, BIOTHAI and GRAIN

December 2007

Despite the uniqueness and diversity of the many struggles against bilateral free trade and investment agreements, there are a number of common elements. [1]

- FTAs and BITs are part of a divide-and-conquer strategy by economic and political elites seeking new allies, new markets and greater power and control. This often forces people to fight specific negotiations and agreements, involving two (or, in the case of sub-regional or inter-regional FTAs, a few more) governments. This can result in fragmented and isolated movements, even though the agreements themselves are very similar.

- FTAs affect so many issues that national coalitions tend to form from many sectors: farmers, public sector workers, indigenous peoples, fisherfolk, artists, scientists, churches, media workers, people with HIV/AIDS, teachers, women, university students and academics, politicians, and so on.

- The secrecy of bilateral trade and investment negotiations distorts national democratic processes and often causes fractious domestic political problems regarding constitutionality of the deals, who has authority to approve such agreements, the jurisdiction of courts, implications for local governments, and so on.

- In many cases, the adoption or rejection of an FTA becomes a national electoral issue (e.g. Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Australia). In some cases, it has formed part of movements to depose national leaders (e.g. Thaksin in Thailand or Gutiérrez in Ecuador).

Challenges in the campaigns and processes to stop FTAs

A number of important challenges arise from different struggles against FTAs.

Resist vs participate: While many people share a common understanding that FTAs are essentially tools to spread neoliberalism, some NGOs and others engaged in campaigns to stop FTAs often take a reformist approach. In some countries, NGO representatives or other "civil society" groups participate in negotiating teams, advise governments on "better" terms to achieve, lobby for the exclusion or inclusion of this or that element, and so on. This is not unique to FTA or trade policy struggles, but can be seen as weakening wider movements for social change, dampening resistance and leading to co-optation.

|

Constantly choosing the lesser of two evils is still choosing evil. — Jerry Garcia, musician [2] |

"Alternatives": In many campaigns and struggles to fight FTAs, the question "What is your alternative?" is posed to critics, especially by governments which resent challenge from social movements. [3] For those who understand that an FTA’s overarching purpose is to further the domination and control of, say, Washington and US TNCs over your own country, this question makes little sense: why in the world would people’s organisations feel the need to propose an alternative route to this goal? For others, articulating alternative - fairer or more beneficial - trade or investment relations with powers like the US or the EU is essential to the credibility, direction and purpose of people’s movements. Attitudes towards this "alternatives" question often boil down to whether one believes that social justice can be achieved under neoliberalism, or under the grip of capitalism altogether. For some, there seems to be no need to step out of this frame - or, as some people lament, that we don’t have another frame and must get on with what we’ve got. For others, no alternative is possible within this frame and we must find a different one. In short, the old "reform versus revolution" dilemma is very present within today’s social activism against FTAs.

Regional integration: Governments of the South have long tried to form blocs to counter the weight of former colonial powers and pursue their "development" strategies in neighbourly co-operation. Today, regional integration has become an idealised counterforce to the push for FTAs from imperial powers, especially the US, Japan and the EU. The election of supposedly progressive leftist leaders in much of Latin America, and especially the active role of Hugo Chávez, has sparked a wave of new interest in forging links between Latin American countries as a way to move forward, not only among governments but also among NGOs and other groups. Ideologically, much of the talk coming from the leadership is about building new trade relations based on complementarity rather than competition. In practice, many of the projects being brokered are giant new business deals fronted by "Latin American" capital. It seems to be the same old programme of agribusiness expansion, mining concessions, highways and telecommunication deals, the recycling of petrodollars or the boom for agrofuels, but this time led by the region’s elites, whether public or private. The glimmer of South-South business deals [4] as a way to foster independence from the North is being flagged as the way forward in the sub-regions of Africa, Asia and between emerging Southern giants, as in the case of the India-Brazil-South Africa alliance. The "people" component of this regional integration wave is so far proving slippery, top-down or barely existent. But many NGOs and others are intrigued by the promise that South-South cooperation offers to counteract the imperialist relationships embedded in North-South FTAs. A nagging problem this raises, however, is the relationship between states and people.

Today, rhetoric aside, hardly any state is not penetrated by neoliberal values.

Some key learnings

It would be impossible to sum up all the learnings from years of peoples’ struggles against bilateral FTAs and investment agreements around the world. However, a number of important points stand out.

1) The struggle against FTAs is a struggle against neoliberalism: Bilateral free trade and investment agreements are just one face of contemporary capitalism and imperialism which are advancing through different means at local, national, regional and global levels. The comprehensiveness of many FTAs, affecting so many facets of our societies and economies, and the multi-layered and multi-sectoral nature of many anti-FTA struggles, attest to this dynamic. Korean and many Latin American experiences drive home the message that FTAs and investment treaties are not merely trade pacts, but structural tools of overall "regime change" that aim to consolidate a very deep basis for new power relations in their countries. Those relations are not just economic ones, reshaping rules so that TNCs can do whatever they want, wherever they want. They are also geopolitical, pulling countries into much larger struggles for leverage and influence between states, be they old or emerging hegemons.

2) Overcoming compartmentalised approaches: In the fight against FTAs and investment treaties, we should be wary of approaches that compartmentalise or bureaucratise either the analyses or the struggles. It may be tempting to frame campaigns against FTAs within the terms set by the agreements themselves. But in doing so, one can miss the underlying threat posed by the totality of the agreement. NGOs often tend to focus their work and campaigns on narrowly defined "issues". Such compartmentalisation can lead to positions that argue that amending a particular provision of an FTA constitutes a victory. Or it may lead to challenges against the process of trade negotiations as being undemocratic, demanding only that certain NGOs or sectoral groups are listened to, rather than focusing on the fundamental injustices in the content of these deals. Similarly, the bureaucratisation of people’s struggles can lead quickly to a damping down of resistance and foster a form of ideological pragmatism on the part of larger NGOs and trade unions that is easily co-opted by governments and the corporate sector.

3) New meanings of public and private: Many social struggles against FTAs make appeals to the state, or to state institutions, in one way or another. After all, it is governments that sign FTAs. Politicising the actions of the state in relation to international treaty-making is one way to raise public awareness and mobilise people against these agreements. But people’s movements against FTAs often put forward and defend a notion of "sovereignty" against the new wave of privatisation and deeper integration with transnational capital that these deals promise. Similarly, moves to defend state constitutions, use them as some kind of litmus test for what is fair or foul play in an FTA process, or leverage them to block or modify specific provisions frequently emerge. But one must ask: who is the state? What kind of sovereignty do we mean? Who defends or represents public interests? Who is the government really working for? If Korea, for instance, really ought to be called the Republic of Samsung, as FTA activists there say, what are we dealing with? States have never stood outside capitalism. They are key actors, and the lines between states and private sector interests have become so blurred that it is difficult to consider them apart. The transnationalisation of capital and the current emergence of new and powerful corporate empires in countries like China, Brazil, Mexico, Singapore or India further challenge our perceptions of who and what we are actually fighting against in these FTA battles. Many experiences fighting FTAs illustrate that the state is not "the people", but rather an instrument of elite power, domestic or foreign capital or political interests. Furthermore, the corporations standing to gain from these FTAs are not just US or Japanese ones; they are increasingly "Third World" TNCs eager to expand their own market control and profit margins. The Zapatistas taught us to take a critical stance in relation to the state when NAFTA came into effect. Fifteen years later, many movements resisting neoliberalism continue grappling with tensions around state power and interests.

4) Grounding in local struggles: FTA struggles highlight the importance of resistance firmly grounded in local and national contexts, but which connects to regional and global perspectives. The framing of FTAs as bilateral, regional or sub-regional, not to mention the plethora of different names for them (e.g. EPAs or CEPAs), can divert attention from the bigger picture, whether in the context of North-South or South-South deals. Strategies that emerge from strong local organising are the ones most able to map the terrain of struggle, to identify key local and international players pushing specific agreements (and specific provisions of agreements), to know their weak points, histories, styles of operating and how they are connected, and to oppose, expose and challenge those pushing FTAs and their strategies. Alongside this, technical policy analysis needs to be informed by and connected to the realities of people’s struggles, not the other way around. These forms of knowledge are increasingly important as resources for other movements which find themselves confronting the same strategies and players in different parts of the world.

5) Avoiding the pitfall of co-optation: Governments, corporations and some so-called “civil society” organisations that are essentially pro-free market have learned from previous campaigns against corporate power, structural adjustment programmes and free trade and investment agreements. They seek to avoid confrontation, and to maintain control over the parameters of public awareness about these agreements. They increasingly use the language, strategy and tactics of “dialogue”, “consultation” and “participation” in order to undermine - and to divide and rule - opponents of FTAs. These processes are frequently designed as cosmetic safety valves to allow “responsive” or “constructive” critics to vent steam about their concerns, and to marginalise - and too often criminalise - more militant or critical opponents. They serve to add legitimacy to fundamentally unjust and anti-democratic processes, and to mask the disproportionate influence of TNCs and domestic elites in the imposition of these agreements. In fighting such methods, groups can draw attention to the unequal power relations that lie beneath FTAs, and to the fragility of the arguments in favour of neoliberal capitalist regimes. In several FTA struggles, state and big business attempts to limit terms of the debate have been denounced, and movements have framed their struggles based on their own platforms, rather than in a narrowly defined space for stage-managed “civil society consultation”.

6) The struggle post-FTA: If we understand the fight against FTAs as a fight against new tools of much older processes of capitalist and imperialist invasion, then we know that the struggle does not end when an FTA is signed or takes effect. FTAs often aim at advancing and locking in extreme neoliberal economic and political models, and in most countries there are many ongoing struggles against such policies - such as the fight for access to water, for publicly funded health care and education, for genuine agrarian reform, for access to affordable medicines, or against the creeping corporatisation and privatisation of agricultural biodiversity. These struggles are long-term and do not end when a government adopts an FTA. The experience in Mexico is quite clear about this. NAFTA in and of itself is still unfolding and gaining shape; it is not just a piece of paper. Over the years, Mexican farmers, textile workers, indigenous communities, political groups and others, rather than adapt or adjust, have had to keep on with the struggle and take it to new levels in a worsening context of poverty and disenfranchisement. The Costa Rican experience shows that fighting FTAs through socially broad national processes may provide the dimension and depth that gives rise to new forms of solidarity and people power in the longer term. Moreover the effects of FTAs and BITs expand not only through progressive implementation, but also through successive interpretations which give ever stronger protections to the interests of big capital. This is particularly clear with the provisions of the EU’s FTAs, which are very open and vague, and subject to "interpretation" every three or five years. This is another reason why the struggle against these agreements must continue.

7) Exploiting contradictions: Without minimising the powers that are pitted against social movements fighting FTAs, it is important to recognise and politicise the contradictions that exist among the forces behind these deals. States and corporate interests are fraught with contradictions and are more fragile than they may seem. It is easy to see neoliberal globalisation as an unstoppable force that moves only in one direction. But in the geographies and rationales of different forces pushing FTAs there are many contradictory and sometimes conflicting realities. These may take the form of disagreements among government ministries or agencies in relation to parts of an agreement. They may appear in the competition between TNCs for markets, access to resources or guarantees on investment. There are conflicts between business groups and governments over the primacy of corporate interests versus so-called national security concerns. Likewise, much work has been done in highlighting disparities between claimed benefits of agreements and their real impacts. These contradictions can be highlighted and used more by social forces.

8) The need to learn from each other: Bilateral free trade and investment deals deliberately sow divisions. One of the most important examples of this is the division between peoples on both sides of the countries directly affected by a given FTA. Another is the division between FTA struggles in different countries. Much more needs to be done to bridge these divides. People in Thailand, for instance, mobilised against the Thailand-China FTA as it became clear how much harm it would cause to Thai farmers, especially fruit or garlic producers in the north of the country. But the reality of the struggle took on a different dimension when they went to China and talked to garlic farmers there. Contrary to what they imagined, the FTA, which had put many Thai garlic growers out of business, was of no benefit to Chinese garlic producers. It was the middlemen, the traders, who were making all the money. We have to share experiences, learn from each other in much deeper ways and build common fronts of action. The same is true at the global level. Latin America has had the misfortune of being the vanguard of the struggle against FTAs because of US aggressiveness towards what it considers its backyard. Many people in other parts of the world have learned a lot from Latin American movements and are eager to learn more from them. We need to intensify this reaching out and learning - from the grassroots, not from the elites - to strengthen the fight. Much has been shared in terms of stories and analysis, understanding impacts and situations. But not enough yet in actually working and fighting together, whether across the Thailand-China border or as people of Peru and Senegal in common struggle.

Moving forward

Free trade and investment agreements, and the state, private sector and other players that promote them, must be critically analysed and challenged in national, regional and international contexts. This work needs to be situated in an understanding of the nature of capitalist restructuring, histories of colonialism and imperialism, as well as the shifting geopolitical priorities of state and corporate players. In strategy-building against FTAs, we can draw on conceptual resources and strategies from older histories of resistance to other forms of imperialism - local struggles against privatisation, anti-war movements, women’s movements, indigenous peoples’ struggles for self-determination, resistance to World Bank/IMF structural adjustment programmes or opposition to the WTO. While all of these processes are interlinked and have their own specificities, resistance movements against FTAs need to confront the overall system that lies beneath all of these.

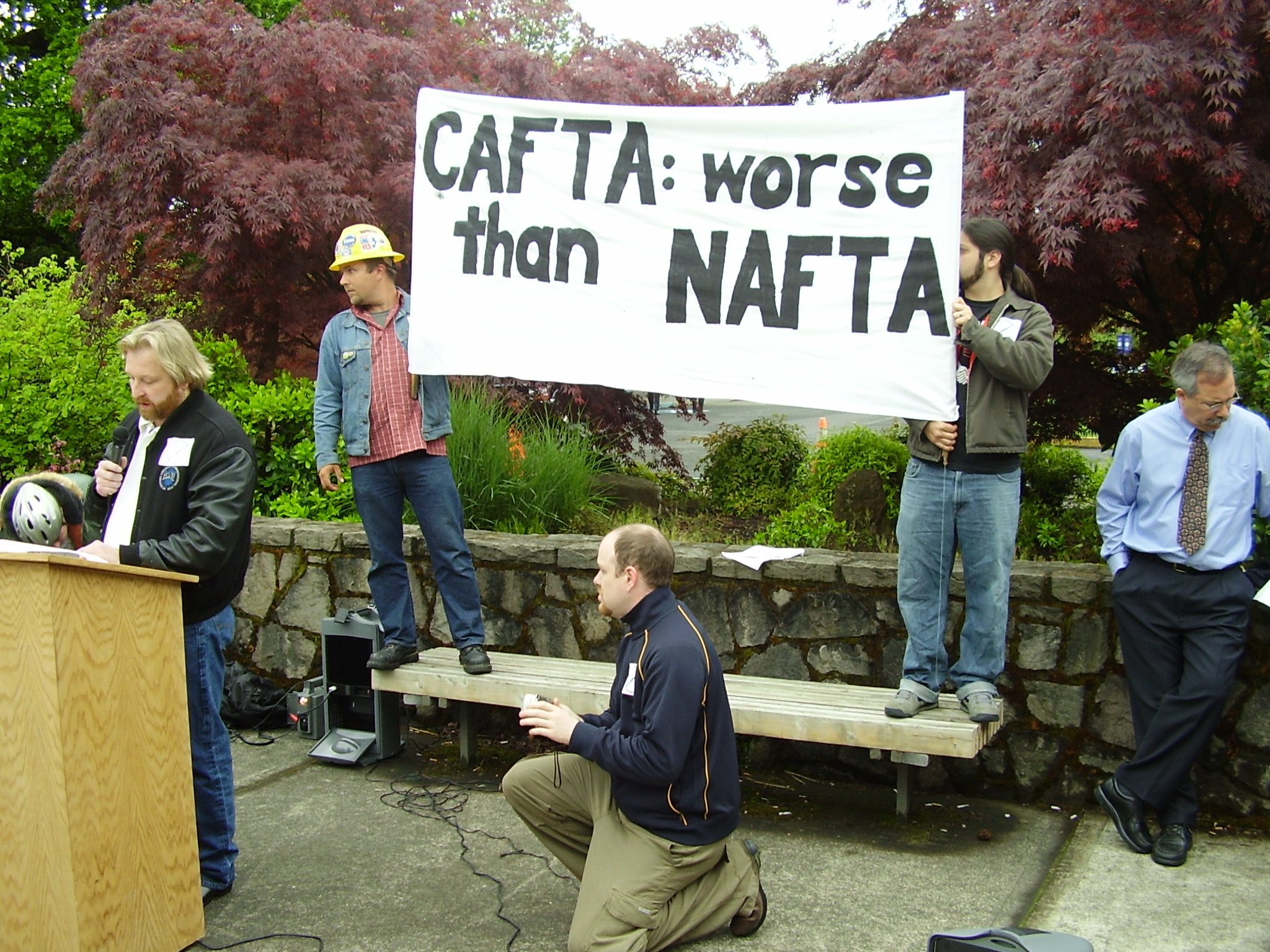

In struggles against FTAs, we also need to be more alert to invisible threats posed by various forms of finance liberalisation and the emergence of relatively new financial instruments, in a context of a deepening financialisation of much of the world economy. The mobility of capital is enormous today and it is growing further through finance liberalisation. This makes it harder for social movements to trace and uncover structures of corporate ownership and control. Many FTAs, like the US-Chile FTA, openly attack capital controls where these exist. And CAFTA radically departs from earlier agreements, such as NAFTA, by applying US investment rules to sovereign debt, severely threatening Central American countries’ ability to stave off or cope with financial crises. [5]

FTAs can be potent, enforceable tools to advance the power of TNCs together with the geopolitical and other interests of governments. The Bush administration’s outsourced war, occupation and restructuring programme in Iraq is a clear example of this, linked as it is to Washington’s aggressive free trade and investment policies in the Arab world, which are aimed at achieving "normalisation" of the region’s relations with Israel. Major powers - which involve the state and corporations working very closely together, whether in Beijing or in Brussels - are using FTAs as one means to re-carve the world into new or renewed colonial spheres of influence. So while critically challenging “our” governments about free trade deals, we cannot rely on their political will to stop them. On the contrary, many people’s struggles against FTAs have brought into question western "democratic" models of governance, showing that these democracies are merely formal. This is thrusting us deeper into the challenge of how to construct other social orders. We must build counter-power to both states and corporate capital through consolidating, strengthening and broadening peoples’ movements. For that to succeed, we need to work more together and build closer relations between people’s movements in the struggle against neoliberalism - starting from the ground.

Notas:

[1] For a broader and more collective analysis of similarities and differences across the struggles, see "Fighting FTAs: workshop summary report", September 2006, http://www.bilaterals.org/article.php3?id_article=5803

[2] From the email signature of someone involved in the NAFTA struggle in Mexico.

[3] The European Commission takes an even more defensive attitude by asserting over and over that "there is no alternative" to the Economic Partnership Agreements that it is pushing on African, Caribbean and Pacific states.

[4] The business deals - from joint ventures to direct investment contracts - are complemented by a slew of preferential loans, aid packages and other financial measures. We may soon see the emergence of a South-South philanthropy industry!

[5] Sovereign debt refers to the bonds, loans and other securities issued from or guaranteed by national governments.