20 years of free trade in Morocco, the dominant class cashes in

All the versions of this article: [English] [Español] [français]

In 2024, bilaterals.org celebrates its 20th anniversary. During this time, bilaterals.org has served as a collaborative and open online platform supporting struggles against free trade and investment agreements around the world, and campaigns against RCEP, TPP, the ISDS mechanism and many other processes.

To mark the occasion, we are publishing a series of five articles written by the movements and activists who have been at the heart of these campaigns all along. The articles aim to take stock of what has happened over the past 20 years and to look ahead to the resistance against free trade agreements in the years to come. They share experiences from Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin America, connecting the dots between different struggles.

- 20 years of free trade in Morocco, the dominant class cashes in

—

20 years of free trade in Morocco, the dominant class cashes in

by Larbi El Hafidi | Member of the national secretariat of Attac- Cadtm/ Morocco, 25 November 2024

Trade has always been at the service of the ruling classes, at least in the capitalist era. The aim of finding outlets for their goods explains the colonialists’ ambition to conquer distant lands and subjugate their populations. Even before the colonial era, Morocco was forced to sign several trade agreements. In 1856, against a backdrop of rivalry between imperialist powers, this was the case with the Anglo-Moroccan treaty, which included a trade agreement and granted the United Kingdom ’most-favoured-nation’ status. [1] During the colonial period, the French and the Spanish dominated foreign trade, each in its own zone of colonisation. France also used Morocco as a backdrop for sourcing agricultural products. Formal independence has not changed the status quo, and the country’s trade remains closely linked to the former colonial powers, especially France.

With capitalist globalisation, free trade agreements (FTAs) have become the main instrument for organising international trade. The giants of the world use debt and their domination to conclude these FTAs. The World Bank (WB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) are catalysing and encouraging this trend. In January 2012, the WTO counted more than 500 FTAs, many of them concluded by the European Union (EU). [2] [3]

Agreements signed by Morocco

Morocco has signed 56 free trade agreements of varying size and scope. Some of these have been signed with economic groupings (such as the European Union, the European Free Trade Association or the African Continental Free Trade Area), others are multilateral (such as the Agadir Agreement and the Greater Arab Free Trade Area) or bilateral. [4] In this article, I will limit myself to discussing the examples of the agreements signed with the EU, the United States and Turkey.

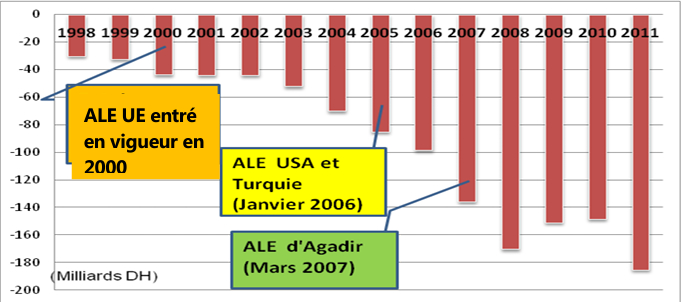

In general, if we look at Morocco’s trade balance with its trading partners through FTAs, it is easy to see that the Moroccan economy is losing out. These agreements always result in a net transfer of money out of the country. The graph below illustrates this result:

Evolution of the trade balance

The signing of FTAs with the European Union worsens Morocco’s trade situation, which has already deteriorated following FTAs with the United States and Turkey.

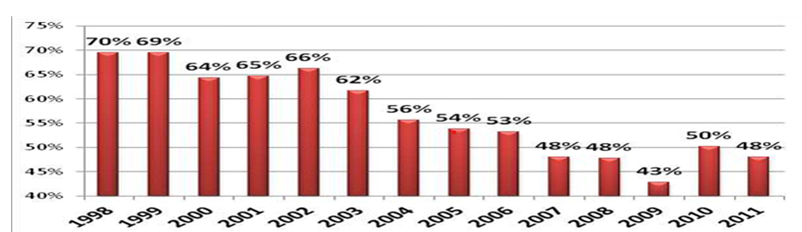

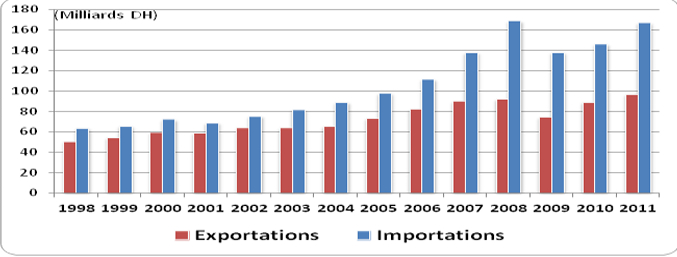

Evolution of the trade deficit (1998-2011)

There are three main reasons for this:

1. The level of development of the Moroccan economy is low in comparison with its trading partners. Morocco imports high value-added goods and exports low value-added raw or semi-processed products. The added value of agricultural products is also low because imported inputs are expensive. As a result, exports never cover imports:

Rate of coverage of imports by exports

2. Morocco’s negotiating position is weak. We are negotiating with the 27 countries of the European Union as a bloc and with the United States, a world power. This weakness is compounded by other political and technical problems. For agreements already concluded, there is no central coordinating body, which has sometimes led to conflicts of competence between certain departments. The example of the extension of the sectoral scope of the agreement with the European Union is significant in this context. Negotiators also internalise the colonial mentality. The result is forced submission and loss of sovereignty. The position of the major economic powers is strengthened by the support of financial institutions such as the World Bank, the IMF and the WTO. Debt is used as a lever to impose free trade.

3. The Moroccan big capitalists are the ones who benefit most from the FTAs.

They monopolise fertile land, own wealthy companies capable of exporting and benefit from export subsidies. The Office Chérifien des Phosphates (OCP) is a semi-public company whose mission is the production of phosphates and their derivatives. OCP is a major contributor to national GDP (around 8%). Although its exports are very significant, its managers are not accountable to the public or to official institutions.

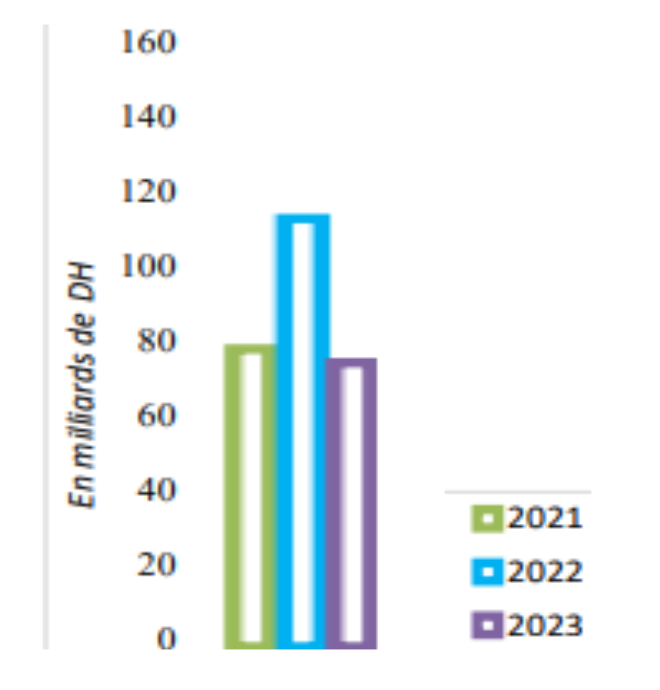

Export value of phosphates and phosphate derivatives

Why these agreements?

Moroccan officials believed, or claimed, that FTAs would help develop exports and attract foreign direct investment (FDI). But the result was similar to that of the structural adjustment programmes imposed by the IMF in the early 1980s. The opening up of the economy led to an offensive against the labour force, the dismantling of labour laws, social insecurity, the deterioration of public services and privatisation. Agreements with smaller economies such as Jordan and Tunisia have had a similar effect, mainly benefiting the big Moroccan capitalists.

The EU is Morocco’s most important trading partner. The agreement was signed in 1996 and entered into force in 2000. Trade more than doubled between 1999 and 2011, with an average annual growth rate of 6.8%. However, the evolution of the rate of exports and imports in monetary terms is uneven. The graph below illustrates this:

Evolution of imports and exports

The result of this opening up of the Moroccan economy is a trade deficit that worsens from year to year. It stood at 11 billion dirhams in 1998 and increased sixfold to 70 billion dirhams in 2011.

Before the free trade agreement between Morocco and the United States came into force in 2006, Morocco’s exports and imports to and from the US were around 3%. After the FTA was signed, trade rose from an annual average of 9 billion dirhams between 2000 and 2005 to 23 billion dirhams between 2006 and 2011. However, the trade deficit also increased from an annual average of 3 billion dirhams between 2000 and 2005 to 14 billion dirhams between 2006 and 2011, reaching 22 billion dirhams in 2011. The cover ratio fell from almost 50% between 2000 and 2005 to 25% between 2006 and 2011. As for the Morocco-Turkey FTA, which entered into force in 2006, the result was again the same: a deficit in the trade balance and a deterioration in the coverage rate.

The current situation

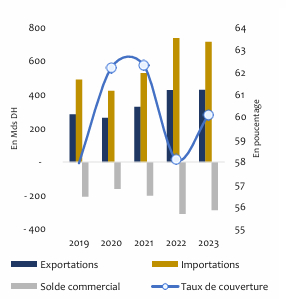

After a long period of this trade experiment, the situation for Morocco is still dramatic and the trade balance is generally unbalanced in favour of its partners. In order to redress this imbalance, the authorities are resorting to borrowing. The following graph summarises the evolution of imports and exports, the trade deficit and the coverage ratio between 2019 and 2023.

Evolution of the trade balance

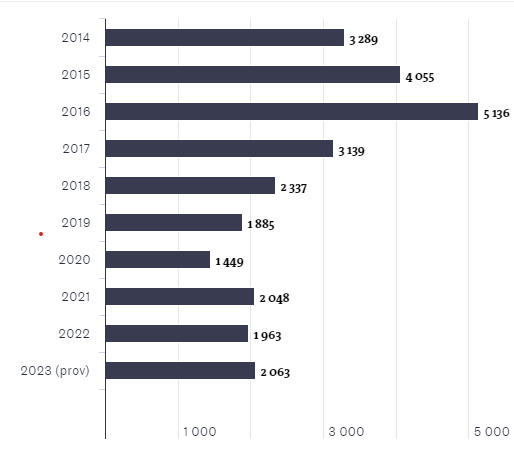

Despite their scale and impact on the population, these agreements are not subject to popular consultation or parliamentary debate, and negotiations are conducted in virtual secrecy. They only guarantee the right to move goods, capital and investment without allowing the free movement of people. And, of course, it is the poor who are denied this right. The number of deaths in the Mediterranean is a clear indicator of the violence these agreements inflict on populations forced to leave their territories in the hope of finding a better life elsewhere. Here is a summary of the victims since 2014:

Deaths and missing persons recorded in the Mediterranean Sea since 2014

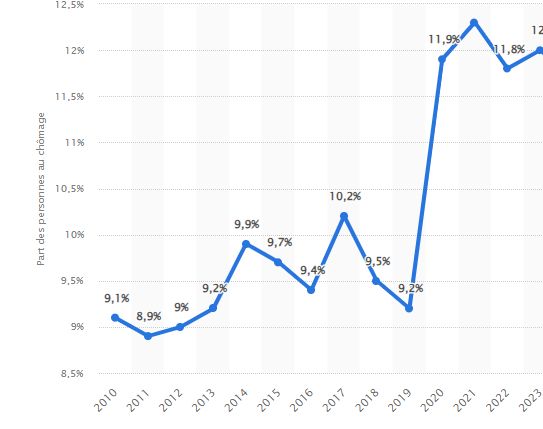

These agreements also involve the dumping of goods from outside the country on the local market, and some manufacturers who have been harmed also criticise these agreements. Here’s what Nabil Tber, president of the Association of Moroccan Notebook Manufacturers and CEO of Imprimerie Moderne, has to say: ’... Over the years, we’ve seen dumping and a desire to flood the market and kill off the Moroccan industry. And that’s something we couldn’t accept as industrialists...’. [5] Indeed, some sectors are being destroyed and thousands of people are being made redundant. For example, the textile sector, which 20 years ago employed more than 10,000 people in dozens of structured companies, has almost disappeared. Nor has unemployment fallen, as the following graph shows:

Share of unemployed workers in Morocco from 2010 to 2023

In order to attract foreign international companies, the national budget is burdened with the cost of infrastructure (development of motorways, railways, airports, ports, etc.). These costs are financed by the debt that the population has to bear.

Foreign companies also impose a high degree of labour flexibility in order to continue their investment/plundering, which is why the Labour Code is now on the agenda of the social dialogue between the unions and the government. The current balance of power and the domination of a pro-business trade union bureaucracy over the trade unions will undoubtedly lead to major setbacks for the working people.

Meanwhile, the process of land dispossession and loss of livelihoods continues. In various regions of Morocco, many tribes have lost their communal lands. This is the case, for example, of land very close to Rabat, in order to build an industrial zone, to extend the airport or simply to build luxury housing estates. As for agriculture, Morocco has become a producer for export. The big capitalist exporters have benefited greatly from the ’Green Morocco Plan’ (around 10.4 billion dollars between 2008 and 2018). The private sector accounts for 61% of this sum. The result is a loss of food sovereignty: we produce what we export and import what we consume. This loss was particularly acute during the COVID19 crisis. In 2022, wheat imports accounted for almost 30% of food. [6]

Small farmers and food crops are left to the mercy of the rain, and people are forced to leave their land to look for work in the big cities or to become agricultural workers on the large capitalist farms. Many young people prefer to leave the country across the Mediterranean in generally inhumane conditions.

The damage caused by the FTAs, in particular the negative trade balance, is rewarded by recourse to debt and the export of raw materials. The result is the extraction of resources: water, phosphates, fish, etc., but also the pollution of soil and groundwater by the excessive use of inputs by the agro-industry.

The conclusion is clear: the struggle against free trade agreements as instruments of neo-colonialism must be a struggle against the productivist capitalist system.

Footnotes:

[1] Omar Aziki, « Le maroc face aux empires coloniaux », 4 octobre 2019, https://www.cadtm.org/Le-Maroc-face-aux-empires-coloniaux

[2] Lucile Daumas , « Le libre-échange dans le contexte de la mondialisation libérale », 3 février 2018, https://attacmaroc.org/fr/2018/02/03/le-libre-echange-dans-le-contexte-de-la-mondialisation-liberale/

[3] Assemblée nationale, « Rapport d’information n°1806, déposé par la commission des affaires européennes sur le bilan des accords de libre-échange », 25 octobre 2023, https://www.assemble e-nationale.fr/dyn/16/rapports/due/l16b1806_rapport-information

[4] For more details: Agence Marocaine de Développement des Investissements et des Exportations (AMDIE): https://amdie.gov.ma/accords-libre-echange/

[5] Ibid.

[6] Calculation made by the author based on data from the Office des Changes du Maroc.