Aust-US FTA 2 years later - ’How to Kill a Country’ Interview

Counterpoint 12 March 2007

Free Trade Agreement

Transcript

Michael Duffy: In July 2005 the US-Australia Free Trade Agreement came in.

Government assured us there would be tangible economic benefits and the

ALP agreeing, with certain qualifications. But many observers couldn’t see

it. Some thought it would actually have bad outcomes. And perhaps the main

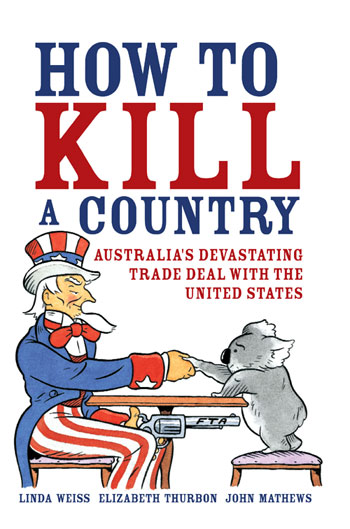

intellectual argument about this was put in a book called How to Kill a

Country. The authors of that were Linda Weiss, Elizabeth Thurbon and John

Mathews, and John joins us now. He’s Professor of Strategic Management at

the Macquarie Graduate School of Management. John, welcome to the program.

John Mathews: Thank you, Michael, it’s a pleasure.

Michael Duffy: I’ve just got to ask you about something. It was discussed

much at the time, it’s not a central point, but why was the thing so long?

Many people commented that a real free trade agreement would take about

three pages, so why was this one 1,000?

John Mathews: That’s a very good point to start with. We were pretty

horrified ourselves as we were observing the progress of the negotiations

on this agreement. We thought, like you, there would be a few key points

that the parties would agree to, we could open up markets on beef and

sugar and so on, and instead we find that six whole sectors where

Australia is strong, like sugar exports, are completely excluded from the

agreement. And we have these long, long chapters, much of which seems to

be taken holus bolus out of American legislation, being incorporated,

effectively, in Australian law.

One example is in the copyright provisions. There’s a long section in the

agreement which brings over, more or less word for word, whole sections of

the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act. It extends copyright provision to

70 years, and it upgrades sanctions from civil penalties to criminal

penalties. You know, you in the ABC might be breaching some small facet of

the copyright law and you’ll be up for criminal penalties. The point is

the Australian parliament has never discussed this, it’s just gone through

and it’s more or less adopted into Australian law. So the length of the

document reflects the legalistic mindset of the Americans in looking to

ratchet up their provision for supporting their trade around the world,

agreement by agreement.

Michael Duffy: But is it also the case that a lot of those 997 extra pages

were qualifications?

John Mathews: Not really, no. They are detailed specifications of what

kind of investments are to be allowed by Australia from the United States

into this country, what kind of contracts for government procurement are

to be opened up to Americans, the kind of manufactured goods that are to

be allowed into this country, and above all the provisions of the

intellectual property right patent law and copyright law which are to be

harmonised...that’s the nice word for it, but actually we would prefer to

use the word ’institution cleansing’. Basically the United States is

cleansing Australia of its institutions, and that’s what we meant by this

somewhat strange title How to Kill a Country, we meant how one country

gives up its institutions and they’re appropriated or taken over or wiped

out by another country.

Michael Duffy: I’d like to go through some key areas with you in a moment

and I realise that in some of them, 20 months won’t be enough, there’ll be

nothing that one can usually say but I believe in others there are things

that we can say, and we’ll come to that in a second. Is it possible to

give any sort of overview...I mean, in the balance of trade figures, that

might give us some hint of what’s going on?

John Mathews: Yes, sure. Again, modelling was done by the government in

the lead-up to this agreement and we’re led to believe that there would be

substantial economic benefits for Australia. The government ridiculed

anybody who queried that modelling and queried the results of it. But

look, the results are there for all to see. It began, by the way, on the

1st January, 2005, so we’re now two and bit years into it, and in the

first year the balance of trade between Australia and the United States

went down, the deficit grew. In the year 2006 the deficit has actually

gotten worse, yet again. It’s now touching $US10 billion. I say US

dollars, Michael, because the Australian government, to the best of my

knowledge, hasn’t published that figure. We’ve got that figure from US

sources. They’re not trumpeting the benefits of this agreement now in

terms of the overall trade balance between Australia which is

overwhelmingly America’s say, and it’s got better from the point of view

of America in the two years since the agreement.

Michael Duffy: Can you put that into some sort of historical context for

us? Do these sorts of blips happen anyway or is this a marked change?

John Mathews: No, this has been a secular decline, the deficit has been

getting worse and worse. We were just into deficit about ten years ago and

it’s been getting worse ever since. So it’s a steady progressive decline.

Michael Duffy: I’d like to run through a couple of the major areas with

you now and you can just tell us if there’s much to say about them or not.

Agriculture was one that was very much in the news, imports and

exports...let’s start with Australia’s exports. Any significant benefits

yet? Are we selling more to America?

John Mathews: No, we’re not, and the provisions in the agreement were very

lightweight, if you like. On beef, for example, the Americans were going

to open up their market progressively over 18 years. I mean, that’s a

ridiculous kind of concession. But let me say on meat and exports from

Australia that pork producers have been up in arms over this agreement

because the Australian government during the negotiations and since the

signing of the agreement have been weakening the quarantine protection for

the pork industry in Australia, drastically changing it from disease

prevention to disease management, looking at the risks and allowing in

pests and diseases that would otherwise be kept out. And so bad was this

that the pork producers actually took the government to court to have one

of their import risk assessments invalidated, and the government appealed

against that decision. So here we have the pork producers of the country

fighting their own government to get decent standards of quarantine

maintained.

Michael Duffy: This is to stop US pork coming into Australia?

John Mathews: The quarantine standards that Australia has utilised, which

gives a clean and green agriculture, are seen as a trade barrier by US

agricultural interests.

Michael Duffy: To be fair they can be used as a trade barrier, and

sometimes Australia has had standards in these areas much higher than

other countries.

John Mathews: And why not? We’re an island nation and it protects us as a

clean and green agricultural exporter.

Michael Duffy: That leads us into beef rather nicely and I know that Linda

Weiss, Elizabeth Thurbon and you have done a paper on this. This is a

story about, as I understand it...well, it will be about American beef

coming into Australia, in part.

John Mathews: Not so much that, Michael, it’s more a case of American beef

versus Australian beef going into Japan and Korea. Here you have a case

with Mad Cow disease or BSE, Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy, here we

have a case where the European industries, in particular the British

industry, were almost wiped out with Mad Cow disease. The Americans

maintained that they had no problems at all and maintained a stringent

policy of no imports from countries afflicted with BSE. Australia of

course has been all through this without any BSE at all.

The Americans had to change when the US Department of Agriculture had to

admit that there were some cases of BSE, so then their strategy changed,

they were excluded from the markets in Korea and Japan, and they saw

Australian beef exporters getting a leg-in there. Under the Free Trade

Agreement we’ve agreed to a side letter, not even part of the text of the

agreement but a side letter exchange later where we agree to relax our

standards on Mad Cow disease and go with the Americans on trying to get an

international animal health standard that is weaker than the Australian

standard, and that of course puts us on a level playing field as far as

the Americans are concerned in the markets for Japan and Korea.

Michael Duffy: And how would relaxing our standards affect the

international standards and what’s happening up in Japan and Korea?

John Mathews: Because the Japanese and Koreans had very stringent

r12 March 2007

Free Trade Agreementequirements on imports of beef into their country, for consumption of

beef in their country, and quite rightly so, and they’re concerned that

the Americans are not, for example, being all that careful with the way

they export their beef, that there might be some kind of spinal cord

residues in the beef that they export and that might lead to cases of Mad

Cow disease in Japan. The point about this is why would a country like

Australia that has a competitive advantage-we are clean and green, we have

the markets in Japan and Korea-why would we give that away to the

Americans, to our great and powerful friend? That’s the conundrum that we

keep coming up against, Michael, in looking at this Free Trade Agreement

and the trade actions of the Howard government in general.

Michael Duffy: Do you have any thoughts on that? It’s quite a question.

John Mathews: It’s quite a question. If you use the perspective of

national interest, that governments are there to protect the national

interests of the country they’re governing, then you are constantly amazed

by the actions of this government and particularly the way that they’ve

given away whole sectors of Australian industry in the Free Trade

Agreement. But if you change that perspective and you actually say that

maybe the goal of the government is to do favours for our American

friends, then perhaps some of the actions become more explicable.

Michael Duffy: Why would it want to do a favour like that? You can

conceivably see why they might want to go into Iraq for some long-term

perceived political gain or an alliance, but why would they want to

destroy Australia’s beef export market?

John Mathews: That’s an extremely good and relevant question and I can

tell you we’re working on it right now. Have me back in a few months and

I’ll say more on that.

Michael Duffy: The senator and pastoralist Bill Heffernan has said that

the side letter ’binds us to bloody nothing’, his words used in

parliament. You would disagree with that?

John Mathews: Yes. Senator Heffernan is a fine figure and he’s a very good

farmer, but there he’s simply astray of the truth. The side letter

explicitly says in the text of the letter that it forms part and parcel of

the agreement.

Michael Duffy: And essentially we’re committed to helping the US water

down these international standards.

John Mathews: That’s effectively what the side letter on BSE is doing.

Michael Duffy: I understand the Cattle Council of Australia went along

with this. Why would they?

John Mathews: Why would they? Well, again, a very interesting question.

Why would the Cattle Council, why would the National Farmers Federation go

along with these actions? And I think to answer that question you have to

look at the structure of those organisations, you have to look at the way

that rural interests have been carefully structured in a kind of

corporatist process in Australia so that effectively...we were arguing in

this paper that published in the Australian Journal of International

Affairs, effectively the Cattle Council of Australia has become an

extension of the government rather than an independent voice for cattle

farmers.

Michael Duffy: How binding is this agreement? What happens if Australia or

indeed America wants to break one of its conditions at some point in the

future? You talked before about how we don’t have access to certain US

markets for 18 years, so what happens if, come 18 years, they say no?

John Mathews: The point is it’s a trade agreement and therefore there are

strict enforcement provisions. There’s a provision for taking disputes to

a process where they can be arbitrated, and if the Americans find us to be

in breach of the agreement then trade sanctions will be imposed, so it’s a

serious agreement. But how long is it? Well, it’s an open-ended one. The

two countries can have a free trade agreement for ever and it’s binding,

but if a government were to come in in future and say, ’well, looking at

this agreement we can’t see where the advantages for Australia lie, why

don’t we disassociate ourselves from this’, then under the agreement you

can actually give six months notice to terminate in writing and then that

process would go from there.

Michael Duffy: John, what about blood, what’s going on there?

John Mathews: Blood’s an interesting one. You might have noticed over the

weekend the health minister Tony Abbott put out a press release that was

carried in the press over last weekend; Abbot may lift Mad Cow blood ban.

This is an interesting kind of story that’s sourced actually from the

minister’s office. He’s effectively saying, ’Well, we’d like to be able to

have self-sufficiency in blood supplies in Australia, it looks as though

we might be a bit short, so we might have to, if we want to maintain that

policy of self-reliance, we might have to extend the net a little bit,

maybe bring people in as blood donors who had been exposed to certain

conditions in the past such as Mad Cow.’

And he says, kind of ingenuously, that that’s one way of going ahead. What

he doesn’t say, of course, is that there is another option which is to

import blood products. The fact is that the government has been pushing as

hard as it can for that second option. It’s been pushing to open up the

Australian blood market to foreign imports, particularly from American

blood products supplying companies. But that’s not stated in this press

release from the minister, it’s not stated in the stories that are carried

in the weekend press, it’s not even stated in the ABC news. So how is

anybody, listening to that or reading that, to make sense of it? In fact

they can’t make sense of it.

Michael Duffy: But why shouldn’t they just open it up? What’s the problem

there?

John Mathews: The point is, you see, we have an excellent blood supply

system in Australia. We collect blood from our own citizens through the

Red Cross, it’s then passed to the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, CSL,

who fractionate the blood and produce blood products. It’s an excellent

system, it works extremely well. Why on earth would we want to change it?

Well, you have to go back to the Free Trade Agreement to find another side

letter, a side letter this time on blood supply and American firms like

Baxter International saying to their government, the US government, ’This

blood supply contract that the Australian government has with CSL is a

trade barrier, why don’t you see if you can get it taken down under the

Free Trade Agreement?’ So under the chapter on government procurement they

exclude blood products, and then they re-include it under the table

through a side letter. This is what it turns out the government has been

pushing for, even before this Free Trade Agreement came in. So you need to

understand the implications of the Free Trade Agreement to make sense of a

story like this one that Tony Abbott has put into the press over the

weekend.

Michael Duffy: So it seems like one of the things you’re suggesting is

that the government has used aspects of the Free Trade Agreement as an

instrument of domestic economic policy.

John Mathews: Absolutely correct, yes, and again you wouldn’t know that

that’s the real issue involved in this blood supply issue just by reading

these stories where Tony Abbott says, hand on heart, ’We’d like to

maintain the policy of self-sufficiency,’ when in fact the reality is that

under the Free Trade Agreement they have already given undertakings to

open up the Australian blood market. They’ve put an inquiry into place to

look into that and much to their discomfort, that inquiry, the Flood

Report, actually said thanks but no thanks, we’ve got a very good system

in Australia, thanks very much, and we’d like to keep it.

Michael Duffy: I think the agreement was to make it potentially easier for

Americans to invest in Australia. Have we seen much sign of that yet?

John Mathews: Yes, we have. The agreement raised the bar from just $50

million to $800 million for an acquisition that would need to be sent

across to the Foreign Investment Review Board for review. Believe it or

not, one of the first American investments in Australia after the

agreement came into effect was in the resource sector. An American

company, Cleveland-Cliffs, came in and bought an Australian iron ore

exporter, Portman in Western Australia. Portman has lots of contracts to

supply iron ore to China. Indeed, the trade minister Mark Vaile was

involved in negotiating those contracts. He came back after that series of

negotiations and...

Michael Duffy: And that’s the most substantial one to date, is it?

John Mathews: Yes, he said that’s how we’re supporting iron ore exports

from Australia, and boom, that’s the first company snapped up by an

American company under the FTA.

Michael Duffy: We’re out of time, but Professor John Mathews, thank you

very much for joining us.

John Mathews: Thank you very much, Michael, for the time.

Michael Duffy: John Mathews is Professor of Strategic Management at the

Macquarie Graduate School of Management, and he’s co-author of How to Kill

a Country, along with Linda Weiss and Elizabeth Thurbon, and that’s

published by Allen & Unwin back in 2004.

Guests

John Mathews

Professor of Strategic Management

Macquarie Graduate School of Management

Sydney Australia

Publications

Title: How to Kill a Country

Author: Linda Weiss Elizabeth Thurbon John Mathews

Publisher: Allen & Unwin

Presenter

Michael Duffy

Producer

Ian Coombe