Colonisation redux: new agreements, old games

Todas las versiones de este artículo: [English] [Español] [français]

Colonisation redux: new agreements, old games

bilaterals.org and GRAIN

September 2007

— Moana Jackson, Ngati Porou/Ngati Kahungunu, Maori lawyer, 1995

"FTAs and farmers cannot live under the same sky."

— Choi Jae-Kwan, Korean Peasants League, July 2006

The comprehensiveness and range of many of today’s bilateral free trade and investment agreements (FTAs) is striking. Typically, they cover an expansive - and worrying - array of areas and issues, which multiply their impacts across societies and sectors and provoke wide-ranging resistance to them in many countries. The US signed its first bilateral FTA with Israel in 1985. The European Union (EU) has been forging soft "trade cooperation" deals since the formal end of its colonial rule at the turn of the 1960s, moving gradually into stronger FTAs since the 1990s, often following the footprints of the US. The same goes for Western European countries that are not part of the EU and which have been steadily harvesting their own FTAs since a first deal with Turkey in 1991. [1] Australia, Japan and other industrialised countries have been a bit slower to jump on the FTA train, although the 1983 Australia-New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement is an early example of a comprehensive FTA. But governments of the South have historically given more emphasis to forming regional blocs, [2] though in the 1980s several Latin American states penned a rash of small preferential trade deals among themselves. Bilateral investment treaties (BITs) started in 1959, but emerge from an even longer history of "commerce and amity" agreements going back to the 19th century.

Roots of FTA pressure

While some may see the bewildering proliferation of bilateral FTAs and BITs throughout the world as a relatively new phenomenon, it has deep roots. These can be traced back to long before the creation of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), not to mention international trade bodies like the World Trade Organisation (WTO) or its predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The origins of today’s FTA mania lie in a long history of colonial exploitation, capitalism and imperialism - just as many of today’s people’s movements against FTAs trace their own histories to previous generations of anti-colonial, anti-imperialist resistance and struggles for self-determination.

The predecessors of the first transnational corporations (TNCs) that now dominate national and global economies - and sharply influence the spread, scope and priorities of FTAs - brought together state and private capitalist interests, like the relationship between the British East India Company and the British Parliament and Crown, and the agreements stitched up by colonial powers and their companies with newly independent countries of the South.

The tight interweaving of state power, geopolitics and corporate capitalist exploitation is therefore nothing new. Opponents of the US-Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), for instance, remind us to look back in history to understand fully Washington’s economic and geopolitical interests in pushing FTAs on the countries of the Americas. In the 1823 Monroe Doctrine, the US declared the western hemisphere to be its sphere of influence. Any attempt on the part of European powers “to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere” was deemed “dangerous to our peace and safety”. This was reinforced in 1904 with the Roosevelt Corollary, which held that the US had the right as a “civilised nation” to intervene in its southern neighbours’ affairs as “an international police power”. George W. Bush’s trade agenda, and Washington’s military aid to Colombia and Mexico to support US geopolitical and corporate interests, continue this imperialist tradition.

The classic colonial state was structured for the exploitation and extraction of resources. More recently, neoliberal globalisation has forced countries into becoming sources of plunder for TNCs and facilitates the volatile and unencumbered flow of finance capital in various forms. At the heart of the strategy and tactics of FTA "negotiations" - especially North-South ones - lies a ruthless divide-and-rule game plan, struggles among powerful states and corporations (including those in rising powers such as South Africa, China, Brazil and India) over their “spheres of influence”, and a world view that commodifies nature, people and human relations for commercial exploitation and monopoly control. Alongside this we can see struggles and contradictions between contrasting forms of capitalist organisation, and new resource wars over energy, minerals and water, among other things. Over the last few years these processes have intensified a thousandfold.

Argentine political scientist Atilio Boron describes the current era as one "characterised, now even more than in the past, by the concentration of capital, the overwhelming predominance of monopolies, the increasingly important role played by financial capital, the export of capital and the division of the world into different spheres of influence. The acceleration of globalisation that took place in the final quarter of the last century, instead of weakening or dissolving the imperialist structures of the world economy, magnified the structural asymmetries that define the insertion of the different countries in it. While a handful of developed capitalist nations increased their capacity to control, at least partially, the productive processes at a global level, the financialisation of the international economy and the growing circulation of goods and services, the great majority of countries witnessed the growth of their external dependency and the widening of the gap that separated them from the centre." [3]

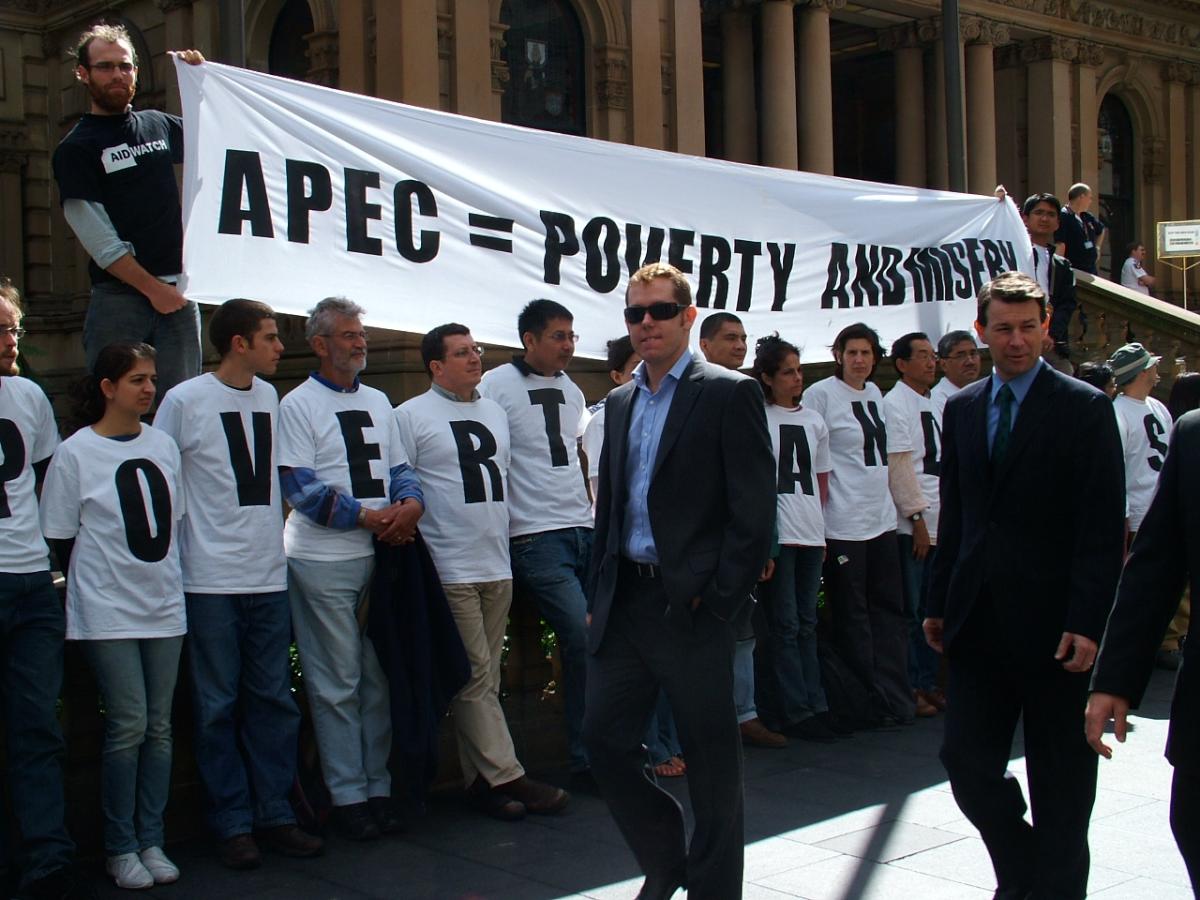

Since the end of the Cold War, people around the world have been sold the idea that neoliberal capitalist models of “development” are the only game in town. Yet despite the seeming ascendancy of TNCs and the “triumph” of capitalism, all has not been plain sailing for those promoting neoliberalism. Internal tensions among and within political and economic elites, as well as external pressure from diverse and growing mass popular struggles against different faces of neoliberal globalisation, have forced its promoters on to the defensive. At the same time, there have been tensions between different forms of regionalism and globalism. During the often uncertain days of the Uruguay Round of GATT negotiations (1986-94) at the multilateral level, many governments pursued on the side regional initiatives such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). At that time, they were seen as the fall-back option, in case the Uruguay Round failed.

Attempts by proponents of neoliberal globalisation to downplay or deny the links between the devastating financial crisis that swept through Asia in 1997-98 and the imposition of economic liberalisation were met with growing scepticism. But, as a remedy, major financial institutions and governments prescribed to the countries most affected more of the same bitter medicine. In the context of growing resistance to neoliberalism, former WTO Director General Supachai Panitchpakdi even claimed that 9/11 was "a blessing in disguise” for the globalisers. [4] Indeed, it has been cynically used ever since as a cudgel with which to bully countries in the South and to impel the push of neoliberalism. As the WTO has lurched from one crisis of legitimacy and credibility to another, and with multilateral trade negotiations fast going nowhere, international summits have become breeding grounds for bilateral FTAs. The WTO’s official stance on the explosive growth of FTAs has changed from one of smug confidence and dismissal to pathetic desperation. The current Director General of the WTO, Pascal Lamy, insists: “I consider that a bit of bilateral pepper in multilateral sauce makes it more tasty. But as we all know, a plate of pepper is not that great a meal.” [5]

Patrick Cronin, senior vice-president of the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies, picked a better analogy in 2004: “With the setback to WTO reform at Cancún, the [Bush] administration is now focused like a laser beam on regional and especially bilateral trade accords.” [6] Laser-guided liberalisation - i.e. bilateralism, through FTAs - allows global powers like the US and the EU to rein in selected countries and restrict the potential for allies to stand up to Western bullying and double standards at fora like the WTO. Through bilateral deals, these blocs have been able to target more precisely those policies or other government measures which they dislike, severely restricting the rights and capacities of governments to maintain sovereign economic, social and environmental policy frameworks.

Locking in and ratcheting up neoliberalism

FTAs are today a tool of choice to lock in and expand the discredited, socially and ecologically destructive model imposed on much of the world in the name of “development” by the World Bank, IMF and regional financial institutions. Structural adjustment programmes, meant to get countries on the right track, include privatising state-owned enterprises and services, slashing public spending, orienting economies towards export, increasing interest rates and taxes, and slashing subsidies on basic consumer items such as food, medicines and fuel. While this model has worked extremely well for transnational capital, it has been an abject failure for the majority of the world’s peoples. The so-called free-market model has led to increased inequalities between and within countries. The World Bank, IMF, Inter-American Development Bank and Asian Development Bank have for decades pushed “technical assistance” and loans to debtor countries in order to adjust them to full trade and investment liberalisation, with the World Bank dramatically increasing its funds to trade-related activities, particularly targeting least-developed countries, transition economies and those in the process of WTO accession. In reality it is aid for trade liberalisation.

Similarly, bilateral official development assistance policies work towards the same goals. Trade and aid linkages have been used by donor governments as leverage to advance the general spread of neoliberalism and specific policy reforms via multilateral, regional and bilateral trade and investment agreements. For example, USAID is a key promoter of biotechnology in the Third World - its work goes hand in hand with US corporate agendas and Washington’s international trade priorities. It offers “technical assistance” to countries engaged in FTAs with the US. Legislative changes to Vietnam’s intellectual property rights (IPR) laws were made under the USAID-funded STAR-VIETNAM technical assistance project, which is supporting implementation of the bilateral trade agreement with the US. [7] Other governments have similar programmes for “trade capacity building assistance”, such as the Canadian International Development Agency’s trade-related technical assistance, and similar programmes of the Australian, European and New Zealand governments. Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry has also created FTA-related aid agreements relating to technical cooperation and personnel development in auto and steel sectors in Malaysia and Thailand.

Meanwhile, in many countries in the North, domestic economic reforms have often broadly mirrored the same neoliberal trends, with waves of privatisation, deregulation and liberalisation in the name of economic growth and competitiveness. For example, New Zealand, Australia and Canada, whose governments are all active players in FTAs, have promoted aggressive free trade policies internationally, while all, to differing degrees, have moved their own economies towards corporatised, privatised and deregulated models. As elsewhere, embracing “free trade” means deploying a package of reforms: minimal controls on big business; unrestricted foreign investment; unlimited export of profits; privatisation of state assets, utilities and services; full exposure of domestic markets to cheap imports; privately funded and owned infrastructure operating through deregulated markets; market-driven service sectors, including social services such as education, transport and healthcare; competitive (i.e. low cost, deunionised) and flexible (temporary, part-time and contract-based) labour markets; and free movement for foreign investors (while retaining strict controls on foreign workers and refugees). The ultimate goal is a hyper-extended neoliberal regime, on a global scale, locked in for ever, with full enforcement machinery.

|

Shopping around Behind every FTA we can find the hands of corporate capitalists. As TNCs and other domestic companies in the process of transnationalisation (often with the support of national governments) have consolidated, restructured, diversified and looked for new markets and areas of profit over the past 50 years, their national lobbying and political leverage have grown, as have their demands for expanded and enforceable freedoms from any regulations that they object to. They - and their financially rewarded political allies - have been forum shopping. When unable to get what they have sought in one venue, they have moved on. Corporations have pushed for the acceptance of binding disciplines that redefine and/or drag areas of what have hitherto been seen as sovereign domestic policy areas - such as agriculture, services and intellectual property - into international trade rule-making through global agreements such as those administered by the WTO. Two examples - investment and intellectual property - illustrate how TNCs have gone from forum to forum in recent decades trying to get what they want, and how FTAs have become their latest weapon of choice. Investment: In the 1960s, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) adopted two non-binding codes on investment liberalisation: the Code of Liberalisation of Capital Movements and the Code of Liberalisation of Current Invisible Operations. It relied on peer pressure for compliance. Then, during the GATT Uruguay Round, the US, the EU and Japan tried to go a step further, pushing for an enforceable investment agreement. But this met with opposition. Between 1995 and 1998 there were yet further attempts to create a binding Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI) at the OECD, which included measures similar to NAFTA’s Chapter 11. After the MAI proposal failed in 1998, due to both external opposition and internal disagreements among governments, renewed attempts to get an investment agreement at the WTO went nowhere. Many states - especially from the South - firmly opposed any resurrection of the MAI at the WTO. But industrial countries have been expanding investment liberalisation through bilateral FTAs and BITs. Bilaterals provide a step-by-step approach which can form a launch pad for more comprehensive multilateral agreements. Once countries are enmeshed in webs of bilateral investment treaties, it will be harder to resist an MAI-type agreement at the multilateral level if negotiations ever start there again in earnest.

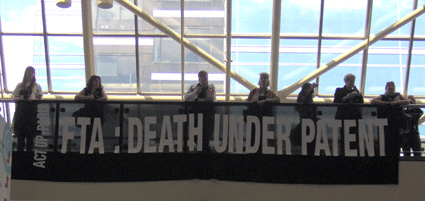

Intellectual property: Ditto with IPR. In the 1970s, governments of the North got frustrated trying to push stronger intellectual property rules through the UN’s World Intellectual Property Organisation. Southern countries were alert to the dangers of strong monopoly regimes, thanks especially to policy guidance coming out of the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), and they used the one-country one-vote mechanism of the UN to block pressure from the North, which was seeking stronger rents from intellectual property due to the changing nature of corporate assets in their countries. In the 1980s, they went to the GATT and put intellectual property on the agenda of the Uruguay Round. The proposed agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) was presented as a tool to help TNCs by stopping the cross-border flow of counterfeit brand-name clothing, music and videos. [8] But it set the stage for aggressively broadening patent rights on microorganisms, crop seeds and life-saving medicines. At that time, most nations did not allow patents on food, pharmaceuticals or other products considered as basic to human needs. The US Intellectual Property Committee - a coalition of 13 large US corporations, including DuPont, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers, and Merck - worked with US trade representatives to draft language that would standardise global IPR laws along US lines, and make them enforceable under what would become the WTO. Such corporate activism greatly shaped TRIPS: a full 96 of the 111-strong US delegation negotiating the text during the Uruguay Round came from the private sector. [9] TRIPS thus became the first binding international agreement to permit corporate monopolies on life forms. But in a compromise with the EU, the US did not get all it wanted. Instead of requiring patents over plant varieties - the seeds farmers sow - the agreement left it open for countries to opt for patents or some other form of plant variety ownership. Since then, the US, the EU and Japan have been working hard to raise this new "minimum standard" up the next notch through their bilateral FTAs. The US imposes patents on plants and animals in its FTAs, while the EU and Japan, for the benefit of their biotech companies, push the UPOV Convention, a set of patent-like rules to prevent farmers from saving seeds. With drugs, a similar and even more sinister scenario has been playing out. At the WTO, the pharmaceutical lobby got only so much; it has been especially irked by a battle over the interpretation of the conditions attached to compulsory licensing and parallel importation of patented drugs. They have thus aggressively turned to bilateral FTAs as a tool to impose far stricter rules preventing the manufacture and trade of generics. Whether in seeds or in medicines, the idea is to stop competition and rake in more profits from longer and stricter monopolies - no matter that we’re talking of food and health. FTAs are the easiest and most effective way for corporations to get what they want right now. |

Notas:

[1] We’re referring to the European Free Trade Association (EFTA): Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Iceland.

[2] Many people might recognise something in the alphabet soup: Mercosur, ASEAN, CAN, SADC, COMESA, SAARC, UEMOA, GCC and so on.

[3] Atilio Boron, "Empire and imperialism: A critical reading of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri", Zed Books, London, pp. 3-4

[4] "Supachai: Tragedy a blessing in disguise", Bangkok Post, 22 November 2001

[5] WTO etraining session, 29 March 2007, https://etraining.wto.org/chat/archive/29mar2007.htm

[6] Daily Yomiuri, Tokyo, 1 January 2004

[7] See US-Vietnam Trade Council website. http:// www.usvtc.org/trade/ipr/STAR_IPR_28apr05.pdf

[8] TRIPS also covers copyrights and related performance rights, layouts of integrated circuits, geographical indicators (as for wines and cheeses), trademarks and industrial designs.

[9] Rob Weissman, "Patent Plunder: TRIPping the Third World", Multinational Monitor, November 1990; see also Aziz Choudry, "Biotechnology, Intellectual Property Rights and the WTO" in Brian Tokar (ed.), Gene Traders: Biotechnology, World Trade and the Globalization of Hunger, Toward Freedom, Burlington, VT, 2004.