In trade talks, it’s countries vs. companies

Bloomberg | March 20, 2014

In trade talks, it’s countries vs. companies

By Peter Coy, Brian Parkin, and Andrew Martin

Beginning in the 1950s, trade negotiators evolved an elegant solution to a vexing problem: the risk that poor countries would seize the oil fields, mines, and factories of Western corporations that operated within their borders. Fearful of nationalization or other harsh treatment, multinationals were holding back on investment. Everyone lost.

The answer was to include language in treaties specifying that disputes between investors and governments would be settled by independent arbitrators, not courts in the country where a disagreement arose. That gave corporations confidence that their projects were safe and helped unleash trillions of dollars’ worth of cross-border investment. Today there are about 3,000 treaties between countries that provide for such arbitration.

Yet that fix is now the subject of a bitter disagreement between corporations and governments that’s impeding progress on two of the biggest free-trade treaties ever, both involving the U.S.: the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

The problem is that to many people, arbitration looks profoundly undemocratic. Countries that sign the treaties give away a lot: The arbitration panels are unelected tribunals of three experts (usually lawyers, one chosen by each side and one picked by mutual consent or a third party) that are empowered to overrule a nation’s highest authorities. The panels have come under attack from environmental groups, labor unions, and developing nations including Venezuela, Ecuador, and South Africa.

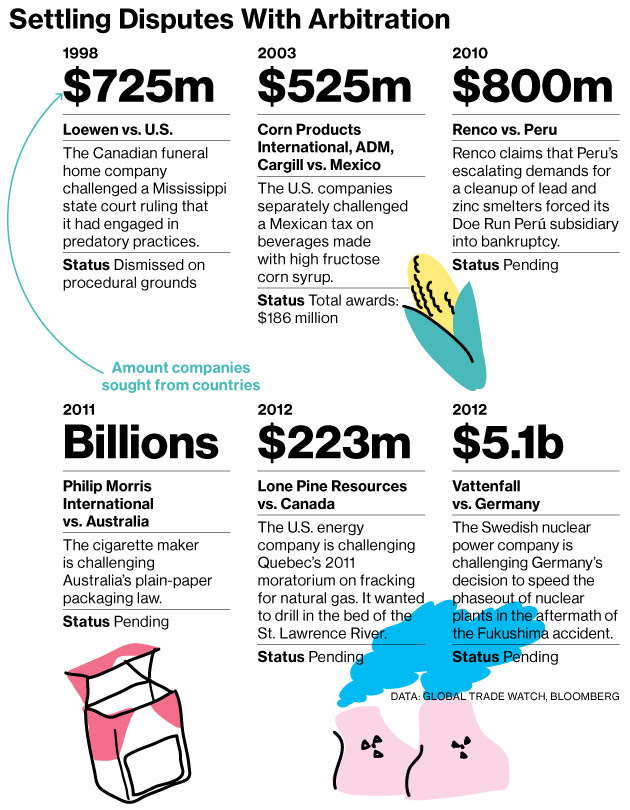

Opponents point to several disputes currently in arbitration where corporations are invoking treaties for protection from local laws. Philip Morris International (PM) has brought a case in Hong Kong challenging Australia’s plain-packaging law for cigarettes. The tobacco company says the law prevents it from marketing its brand, in violation of a treaty between Australia and Hong Kong. Sweden’s Vattenfall, which operates nuclear plants in Germany, is seeking compensation for the country’s planned phaseout of electricity generation from nuclear power, which it says breaks the countries’ bilateral investment treaty. Lone Pine Resources, a U.S. company that has licenses to produce natural gas from beneath the St. Lawrence River in Quebec, wants to be compensated by Canada for a moratorium on fracking in the province.

Lori Wallach, director of Global Trade Watch, a Ralph Nader organization, has called the arbitration system “a quiet, slow-moving coup d’état.” Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio, a prominent arbitration critic, said in an e-mail that the “mere threat of costly litigation” can have a chilling effect on legitimate regulation, such as on tobacco.

To see how arbitration can squeeze a country, consider the case of a lead and zinc smelting operation in South America called Doe Run Perú. The Peruvian government demanded a costly waste cleanup. U.S. billionaire Ira Rennert, who owned Doe Run Perú for more than a decade through Renco Group, said the government’s escalating cleanup demands forced the unit into bankruptcy in violation of the U.S.-Peru trade promotion agreement of 2006. Renco asked a panel of arbitrators to force Peru to pay it $800 million. It also said the country, which once owned the operation, should be liable for any damages arising from a pending lawsuit in federal court in St. Louis alleging that it sickened more than 700 Peruvian children. The case is ongoing.

The voices of opposition are becoming harder to ignore. In January, in response to criticism of the arbitration clauses now standard in nearly every agreement, the European Commission announced a halt to negotiations with the U.S. on the arbitration provisions of TTIP, the ambitious effort to open more trade and investment between the U.S. and the European Union. The commission reaffirmed it was committed to including arbitration in the treaty, but said it wanted a 90-day break for “public consultation” to hear people’s views. A high-profile campaign by opponents could complicate talks long after the listening period ends.

For the U.S. government and other backers of arbitration, a bigger blow came in mid-March when the German government—which has been a staunch supporter of investor-state dispute settlements—said it decided to push for excluding it from TTIP. “Special investment protection rules are not necessary in an accord between the USA and EU,” the German economy ministry said in a statement. It said the rules were unnecessary because “both partners have adequate legal protection” for foreign investors in their courts. The Germans said they’d OK a treaty if the final text addresses their concerns on arbitration.

The Vattenfall challenge to Germany’s nuke moratorium may have brought home the pitfalls of arbitration, says Pia Eberhardt, a researcher with Corporate Europe Observatory, which tracks corporate lobbying of the EU. In an e-mail, the press office for EU trade policy said Europe would make sure the investment provisions “fully enshrine democratic principles.” Australia and Malaysia are leading similar opposition to strong arbitration provisions in the TPP, a 12-nation trade and investment pact.

The U.S. can’t afford to drop arbitration from the big Pacific and Atlantic trade deals, because that would send the wrong signal for future agreements, says Sean Heather, vice president for global regulatory cooperation at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. China, which is beginning to negotiate investment treaties with the U.S. and Europe, could argue that its pacts shouldn’t have to include arbitration, either. That would leave investors in China relying on their governments to intervene with the Chinese government, or, worse, depending on fair treatment in Chinese courts.

Some of the opposition to investor-state arbitration is clearly overheated. It’s one thing for a company to make an outrageous claim against a government and quite another to win. Companies win or settle about half their cases. (Notably, they’ve never won against the U.S.) The arbitration agreement the U.S. wants to include in the Atlantic and Pacific trade pacts wouldn’t give companies a free pass to pollute or break foreign laws. And companies couldn’t claim that any law or regulation they dislike constitutes a “taking” of their property for which they deserve compensation. Arbitration hearings and documents would be open to the public. Still, lots of people have trouble with the idea of giving anyone as much power as the arbitrators have. “They’re supreme court justices for the world,” says Gus Van Harten, a professor at York University’s Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto. “Only they’re not judges, and you don’t know who they are.”

The bottom line: Countries complain treaties that call for arbitration to settle disputes with corporations violate their sovereignty.

Coy is Bloomberg Businessweek’s economics editor. His Twitter handle is @petercoy.

Parkin is a reporter for Bloomberg News in Berlin.

Martin is a reporter for Bloomberg News in New York.