Indonesia latest emerging market to reject investment treaties

Global Risk Insights | April 7, 2014

Indonesia latest emerging market to reject investment treaties

by Kevin Amirehsani

Jakarta’s turn-around is only the latest in a growing chorus of opposition to bilateral investment treaties, meant to attract foreign investors by solidifying FDI protection at the price of curtailing sovereign policy space. The trend may catch on.

For investors whose capital is caught up in various emerging markets, this last year has been particularly difficult. In large part due to the Federal Reserve’s impending tapering, many emerging market (EM) equity and bond funds have been in turmoil. Political crises, from disruptive protests in Thailand to the ongoing instability in Ukraine and Russia, have racked investor confidence in economies with previously bright outlooks. A multitude of developing country “goats” have seen their current account positions deteriorate.

A fairly new threat has also arisen recently: bilateral investment treaties (BITs), regarded by many investors as risk stabilizers in jurisdictions where rule of law and independent judiciaries are lacking, are renounced by a number of EMs.

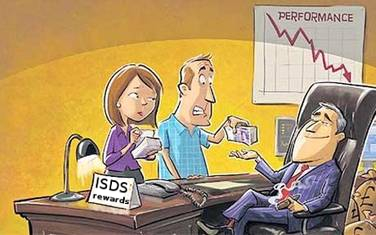

Indonesia is the latest to join the crowd, recently giving public notice of its intention to withdraw from all 67 of its BITs, which it accuses of giving multinational companies too much power in bypassing local courts and taking investment disputes to often-enigmatic investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) tribunals, censured as too investor-friendly.

The reason is almost certainly the threat posed by a number of such arbitration cases Jakarta is currently facing. The biggest involves British resource firm Churchill Mining, which claims a local government breached the 1976 UK-Indonesia BIT when it cancelled its business licenses. It is demanding $2 billion in compensation from ICSID, a World Bank institution for investor-state arbitration. The Southeast Asian giant is also facing threats of arbitration from foreign investors who oppose its new mining law.

To be fair, Indonesia is not imagining a wholesale, permanent renunciation of its investment accords. New, more sovereign-friendly treaty outlines are being drawn up. In this sense, its actions are less extreme than recent attempts to cancel BITs and/or completely withdraw from ICSID in South Africa, Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Argentina.

Perhaps symbolically, Jakarta’s BIT with the Netherlands, its former colonial occupier, was the first to go. However, due to sunset clauses of varying lengths in most BITs, including this one, the treaty provisos will remain for another 15 years.

A number of other EMs are also reconsidering their own investment agreements, including, most recently, India. In an age where labor and environmental standards gain ground in large capital importers, and where governments are increasingly called on to cushion the effects of capitalism on their citizens and domestic firms, it may become politically imprudent not to do so.

But this is not just an issue in developing countries, often regarded as the natural home of investment risk. Western nations are starting to see how many of their own investment agreements, signed and ratified in an era where capital usually flowed in one direction, are invoked by foreign investors. Apotex Inc. v. US and Vattenfall v. Germany are cases in point.

Indeed, the 2004 Model US BIT, a template for Washington’s investment agreements, was notable for its marked narrowing of investor rights and widening of host state policy space.

Moreover, despite a recent softening of its position, Australia announced in 2011 that it will no longer insert ISDS provisions in its BITs. This comes in the midst of Philip Morris and other tobacco companies’ massive challenge of Sydney’s plain cigarette packaging laws.

France and Germany are leading the EU’s resistance to ISDS stipulations in the current Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership negotiations with the US.

However, the BIT backlash is most salient in emerging states, and for good reason. For one, rich countries tend to respect due process and have relatively impartial courts.

In addition, a number of studies suggest that many FDI importers are pressured into signing investment accords by Western nations, and even encouraged by UNCTAD. Others show that on many occasions, developing country officials who sign BITs do not know what the related consequences of adjudication are, or simply do so to procure affluent posts with international organizations later in life.

This leads to a dilemma for investors. Should they invest in a potentially risky (but profitable) EM in the absence of a BIT containing ISDS between their home country and the host state?

One option, albeit controversial, is to “treaty shop” by merely routing the investment through a third jurisdiction, which does contain a strong BIT with the host nation, as is often done with investor-friendly Dutch treaties.

But with Indonesia and a growing crowd of both emerging and developed sovereigns gradually changing the calculus of investment protection, investors may have to engage in an across-the-board rethinking of their FDI strategy. The only constant is that there is sure to be more controversy to come.