Is America mis-thinking its 21st Century trade strategy?

Vox.eu | May 15, 2011

Is America Mis-Thinking Its 21st Century Trade Strategy? (Part 1)

By Richard Baldwin

Two decades of spectacular growth and industrialisation in emerging economies has transformed the world economy, presenting US trade policy with new challenges. This is the first of two columns that consider one aspect of the new challenges – the ways in which the Obama Administration can secure better access for American exporters.

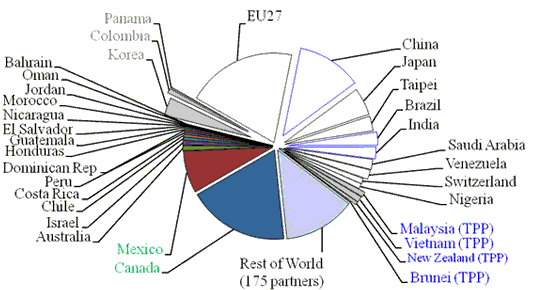

When thinking about American market access – i.e. the tariffs that hinder US exports – the place to start is the markets that matter most to US exporters. About 40% of US exports go to rich nations. The rest is spread widely (see Figure 1). China, Taipei, Brazil, and India together absorb 19% with China accounting for the lion’s share (12% of US exports).

What tariffs do US exports face?

Since 1947, America pursued better market access in GATT multilateral trade negotiations known as “Rounds”. This worked for rich nations, but not for developing nations.

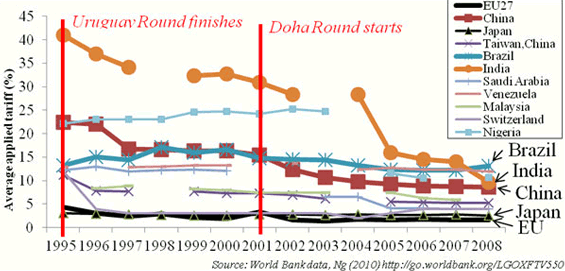

Figure 2 shows that average tariffs in Japan and the EU are under 3%, but others are three to four times higher.

The rich/poor asymmetry in tariffs was done on purpose. Motivated by the now-antiquated thinking that tariffs help development, GATT explicitly granted developing nations free-rider status in 1964. Practicality was another prime motive. Until recently, all developing-nation markets were small, and all commercially important nations were developed. Absolving developing nations from tariff cuts in GATT Rounds allowed the US and a handful of other rich nations to run the GATT – despite its consensual decision-making procedures. The rich nations negotiated a package of tariff cuts that suited them; developing nations went along as free-riders.

From the mid-1990s, two new routes to improving US market access opened up.

* Free trade agreements (the US now has 17).

This route is, so far, unimportant apart from NAFTA which covers 26% of US exports; all the other FTAs combined cover just 6.6% (Figure 1).

* Unilateral tariff cutting by developing nations.

Starting in the late 1980s, developing nations realised that tariffs – especially on industrial parts and components – hindered their industrialisation, and so began to cut them unilaterally. For example, India unilaterally lowered its applied tariff average from 40% in 1995 to about 10% today.

This reversed the free riding. US exporters became the free riders on the emerging economies’ tariff reductions. Much of this happened while the Doha Round talks dragged on (Figure 2). US trade policy had nothing to do with it. It was just good luck for US policymakers. Figure 2 shows, however, that the luck is running out. Unilateralism has moved slower in recent years.

Improving US market access going forward

US industrial exporters still face major tariffs in emerging markets, and US food exporters face major barriers in most of the world’s largest markets. What is the US doing to get these down?

All US trade policy was frozen during President Obama’s first two years in office (to help keep anti-trade Democrats on board for healthcare reform, etc). It was unfrozen when Republicans won the lower house and the Administration started promoting US market access in three ways.

– Getting Congress to approve the three FTAs that President Bush signed but couldn’t get through Congress.

– Embracing a prospective FTA with 8 Asia-Pacific partners (Trans-Pacific Partnership).

– Pushing for a conclusion of the Doha Round.

Because market access turns on market size, the Doha Round is the only one of these three that is likely to significantly improve market access for US exporters before 2020 (although TPP will be important for non-market access reasons like setting the rules on 21st century trade issues).

The 3 pending FTAs and the potential Trans-Pacific Partnership members cover small markets (Figure 1). In total, they will apply to only 6.2% of US exports, with Korea accounting for more than half of this. The 3 FTAs cover 4.3% and the 8 TPP members only 1.9% more when double counting is eliminated (the US already has FTAs with 4 of the TPP partners).

A good Doha outcome, by contrast, would cover almost all of US exports – including China, Taipei, Brazil and India. The reason is that developing nations’ free ride has been cancelled in the Doha Round. It is the first Round where developing nations are required to play reciprocally in a substantial way (although they are asked to make less strenuous cuts).

In all, the Doha tariff cuts would be the biggest market opening initiative ever signed by the US (HLTE 2010). [1]

Obama is closing off the Doha route

The Round, however, is in dire peril and Obama seems to be getting ready to let it die. The current blockage turns on the gap between the US and China and other emerging markets. The US wants them to lower their tariffs to zero on about half of industrial imports in exchange for the US doing the same. As Figure 2 shows, US tariff levels start far lower so this zero-for-zero would mean the US cuts its tariff average by many fewer percentage points than China, India and Brazil. China et al have refused, so the Doha Round is stuck.

Remarks from the US and Chinese Ambassadors to the WTO last week suggest that neither is unwilling to make the compromises necessary to keep the Doha talks moving. The US Ambassador pointedly argued that the impasse on industrial tariffs was not the only one (others are likely in agriculture and services) – as if to suggest that compromise on the current impasse would be futile (USTR 2011).

The Obama Administration has not clearly articulated the reasons for its stance. Talking with WTO Ambassadors from other nations and US trade policy experts in Washington, I gather that there are two key concerns:

* The tariff-leverage argument.

Without a zero-for-zero deal, the Doha cuts would lower US tariffs to the point where it would have few bargaining chips left while leaving emerging market with many. The fear is of a lasting tariff asymmetry vis-à-vis China et al. As the US Ambassador said, Doha would “will set the terms of trade for decades to come and an agreement that does not reflect 21st century realities will contribute neither to the strength of the global trading system nor to the long-term viability of this institution.”

* Too little new market access.

Some estimates suggest that the Doha cuts would provide little new market access (i.e. above and beyond the free-ride access that US exporters have enjoyed since the Round started; see Figure 2). This might or might not be true. One of Doha’s big problems is that a nation’s concessions are clear, but its market access gains are unclear (Schwab 2011). Evenett (2011) argues that US exporters might be mis-thinking the numbers.

PART 2 — 17 May 2011

An ambitious and balanced Doha Round package is within reach (HLTE 2010), but only if President Obama decides Doha is in the US’ strategic interest. Unless US trade negotiators get instructions to start compromising, Doha will die within weeks (of course, China, Brazil and India would also have to match any new American flexibility). [2] There may be a face-saving mini-Doha agreement, but it won’t include any improved market access for US exporters of industrial goods, agricultural goods, or services.

As discussed in my last column, motives for the US’s unwillingness to “split the difference” with China and other emerging markets have not been articulated. It seems to rest on strategic thinking based on the “tariff-leverage argument”. Splitting the difference now would leave America with few bargaining chips (tariffs) while leaving China et al. with plenty. To avoid being locked into such tariff asymmetry, Obama seems willing to let Doha die this year. [3]

This strategic thinking might make sense. Sometimes it is a good idea to run away to fight another day. But it only makes sense if future tariff “battlefields” look more auspicious than the current one. To answer this, we must answer the question: “How and where would the US use the tariff leverage it is trying to save?”

If Doha dies in 2011, the multilateral pillar will be down for a decade

If the US and China can’t find a compromise in 2011 based on the items on the Doha negotiating table, they won’t find one in the future. In particular, 2013 will not be another window of opportunity.

* The US will be less likely to compromise in 2013.

Democrats and Republicans are and will continue to tear themselves apart in fights over the role of government. In this poisonous climate, it is likely that any US President will find it even harder to compromise on multilateral trade liberalisation than is the case today. (Of course two years is a long time in politics and it is possible that a strongly pro-trade President and Congress are elected, but at this moment trade looks to remain a contentious issue in the US for years.)

* China in particular and the emerging markets in generally will not be more willing to compromise in 2013.

China’s exports grew by an average of 20% per year since the Doha Round started in 2001. China and other emerging markets are unilaterally cutting tariffs (mostly on intermediate industrial goods) and undertaking other pro-trade autonomous reforms. They have successfully pursued free trade agreements (FTAs) of their own. These policies have proved to be investment magnets. Their industrial output and competitiveness are booming. In short, they face very little pressure to sign a multilateral tariff cutting agreement that goes as far as the US insists they must.

Given this, multilateral tariff cutting can only work this decade if the range of items on the negotiating table is expanded to include new items that are especially attractive to emerging markets – something to induce China, India, and other emerging markets to accept the US’ market-access demands.

Negotiating an expansion of the agendas, however, would takes years – at least two years – and negotiating the actual deal even longer – at least five years. [4] That takes the new market access gains beyond the year 2020. In short, improving US market access via multilateral tariff cutting is a now or “never” proposition; never meaning not before 2020. US tariff leverage will yield no improvements in US market access at WTO talks for the rest of the decade.

Can the US do better using the free-trade-agreement route?

If Obama’s advisors decide to let the WTO route fail this year, the US has only one way forward – the bilateral road, starting with the 3 Bush-era FTAs, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, and any future FTAs they are able to sign. As mentioned in my last column, the FTAs and TPP would altogether improve American market access to nations that account for only 6.2% of US exports (Korea makes up more than half of this). Part of the problem is that the US already has FTAs with 4 of the 8 TPP partners.

What about future free trade agreements?

A few facts suggest that future US bilateralism will not work well. The US insists its FTA partners fully open their markets to US food exports. This makes it difficult for nations with sensitive agricultural special interests to sign FTAs with the US.

Another major problem is internal to the US; Democrats insist on labour and environment provisions that many nations find intrusive. Small nations that are highly dependent on the US market (like Columbia) may be able to ”grin and bear it”, but large emerging markets, especially those not heavily dependent on the US market will not. Indeed, at least in part to avoid intra-Party conflicts on trade, the Obama Administration has not sought to renew its trade negotiating authority, known as Fast Track, or more formally, as Trade Promotion Authority.

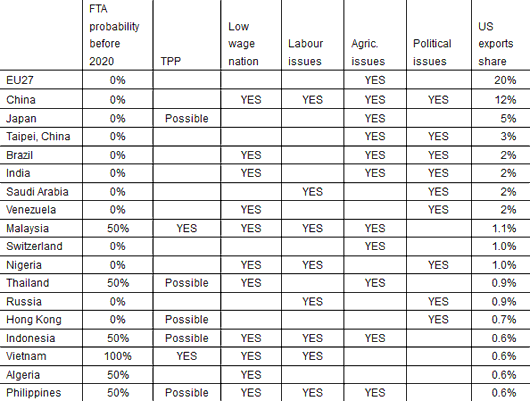

But why discuss this in the abstract? Table 1 lists the nations that don’t have a FTA with the US, but absorb a share of US exports above one half of one percentage point in 2010. The first column gives my guesstimate of the probability of an FTA with the US before 2020; the other columns point out the problems.

There is much art and little science in this, but the estimate for the 6 most important markets seems solid.

* Special interests in the EU, Japan, India, and Brazil will refuse any FTA the US Congress can pass; an FTA with China faces impossible opposition in both nations and this blocks a US-Taipei deal.

Moving down the list to nations that account for at least 1% of US exports, the prospects are mixed.

– Political issues are likely to prevent FTAs with Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, and Nigeria.

– US agriculture demands are likely to prevent an FTA with Switzerland (Hufbauer and Baldwin 2006).

If the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement works out as the US hopes, a number of small East Asian nations may join Malaysia in TPP thus securing US exporters duty-free access. There could, nonetheless, be problems.

The way the US is pushing the shape of the TPP, any nation joining TPP would have to negotiate the equivalent of a new bilateral US FTA and Congress would have to approve the deal. Here Congress’s attitude towards labour and environmental practices in the region may prove an obstacle. Moreover, TPP is not yet a done deal, so I set the probability of a Malaysia FTA at 50% along with Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines. An FTA with Algeria seems reasonably likely, especially given the Arab Awakening, but FTAs with Nigeria and Russia are unlikely this decade for political reasons.

Adding up the likely future FTA partners (Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Algeria, and the Philippines) yields improved market access on only 4.4% of US exports.

Falling behind in the market access game

If the Doha Round ends with a face-saving mini-package or worse, the whole world will see that conflicts between the US and emerging markets – especially China – will stall multilateral tariff cutting for years. With multilateralism dead for a decade, most nations will turn to regionalism – or more precisely, turn to regionalism with even greater vigour, since they are already pursuing FTAs much faster than the US is currently. With the FTA floodgate open, how will the US fair in the bilateral market access game?

In the bilateral game, the US has enormous advantages – its huge market for imports, and its huge willingness to internationalise its supply chain via FDI, offshoring, etc. But it also has the big disadvantages mentioned above – its agriculture and labour interests. The US’s two largest export competitors – the EU27 and Japan – do not have these problems.

By the time Obama or his successor turns back to trade policy in 2013:

– The EU will have equal or better market access in all of the US’s main export markets: the EU itself, Canada, Mexico, Korea, and India. With a strong push – and a failed Doha Round might provide just such a push – an EU-Brazil FTA is also possible (perhaps via an EU-Mercosur deal).

– Japan has or is likely to have equal or better market access in India. It is also seeking agreements with the EU, Canada, and many East Asian nations.

The good news for US is that China will have enormous difficulties in signing FTAs with the markets that matter the most for US exporters; its problem is the hyper-competitiveness in industrial goods.

Will is the Trans-Pacific Partnership work?

The strong point in the US regionalism strategy is the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The current members are too small economically to have a noticeable effect on US market access, but the great hope is that signing the agreement will trigger a domino effect which draws in all APEC members (except perhaps China and Taiwan).

Lewis (2011) notes, however, that a domino outcome is unsure and US negotiating tactics – intended to minimise short-term political hassles – are reducing its strategic potential. Lewis writes: “The more the TPP looks like a series of bilateral US FTAs with exclusions for products the United States considers sensitive, the less likely the TPP will attract other countries to accede”. She continues: “the TPP agreement has the potential to become a new paradigm for trade agreements, to help the US re-assert its position in the Asia-Pacific, and to begin the process of defragmenting international trade.” But, the US “must be careful not to shoot itself in the foot by following a ‘business as usual’ approach … .”

Concluding remarks

For decades the US has pursued better market access via multilateral and bilateral negotiations. The future, however, does not look bright along either road. [5]

– If the Obama Administration doesn’t start thinking strategically about the WTO, the Doha Round will die this year and with it any possibility of multilateral tariff cutting before 2020.

– The bilateral route looks somewhat more hopeful, but all the FTAs that are likely to be signed this decade cover less than 5% of US export markets.

– US export competitors, the EU and Japan, are likely to be far more successful at improving market access bilaterally, thus leaving the US to play catch-up (as with Korea).

The Obama Administration should rethink the merits of allowing Doha to die this year in order to maintain US tariff leverage. Opportunities for using the leverage in Obama’s second terms are far grimmer than many of Obama’s advisers seem to be assuming.

Moreover, as the TPP talks have shown, the US does not need high tariffs to negotiate 21st century trade agreements. Four of the 8 TPP partners already have FTAs with the US and yet are still eager to negotiate. The reason is that 21st century FTAs are not about tariff preferences, they are about making it easier to do business internationally in the complex, interconnected world of today (Baldwin 2011).

References

– Evenett, Simon (2011). “The dubious hold-up over Non-Agriculture Market Access (NAMA)”, in Baldwin and Evenett (eds.), Why World Leaders Must Resist the False Promise of a Doha Delay, A VoxEU.org Publication.

– Schwab, Susan (2011). “After Doha: Why the negotiations are doomed and what we should do about it”, Foreign Affairs, May/June.

– USTR (2011). “Statement of Ambassador Michael Punke US Permanent Representative to the World Trade Organization”, 29 April.

Baldwin, Richard (2011). 21st Century Regionalism: Filling the gap between 21st century trade and 20th century trade rules, forthcoming, November 2010.

– HLTE (2010). “Interim Report, The Doha Round: setting a deadline, defining a final deal”, Interim Report of the High Level Trade Experts Group.

– Hufbauer, Gary and Richard Baldwin (2006), “The Shape of a Swiss-US Free-Trade Agreement”, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington.

– Kucera, David (2004), “Measuring trade union rights: A country-level indicator constructed from coding violations recorded in textual sources”, Working Paper No. 50, International Labour Office, Geneva, October.

– Lewis, Meredith (2011). “The Trans-Pacific Partnership: New Paradigm or Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing?”, Boston College International and Comparative Law Review, 27.

– Sari, Dora and David Kucera (2011). “Measuring progress towards the application of freedom of association and collective bargaining rights: A tabular presentation of the findings of the ILO supervisory system”, Policy •Integration Department, Working Paper No. 99, International Labour Office, Geneva, January.

– Schwab, Susan (2011), “After Doha: Why the negotiations are doomed and what we should do about it”, Foreign Affairs, May/June.

– USTR (2011), “Statement of Ambassador Michael Punke US Permanent Representative to the World Trade Organization”, 29 April 2011. https://geneva.usmission.gov

Footnotes:

[1] The least developed nations don’t have to do anything, but their markets are trivial in terms of US exports.

[2] The next decision point is a 31 May 2011 meeting in Geneva of all WTO members.

[3] Phil Levy of the American Enterprise Institute points out the lack of support may not be so strategic, but rather a case of benign neglect. “President Obama is not anti-trade; he just doesn’t particularly grasp its importance and sees it as politically awkward. If someone were to present him with a Doha package that had domestic support, I suspect he’d be glad to sign it. He just doesn’t want to lead on the issue.”

[4] This one might take even longer as it would be viewed as setting “the terms of trade for decades” in the words US Ambassador to the WTO Michael Punke quoting from Schwab (2011). This means the multilateral route to better market access will be shuttered till at least 2020.

[5] Of course all this may have been done on purpose; a standstill on trade may suit the Administration’s domestic politics, but it won’t serve US export interests.