ISDS: Who wins more, investors or states?

IISD | June 2015

ISDS: Who wins more, investors or states?

By Howard Mann, Senior International Law Advisor, IISD

On June 24, 2015, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) released its World Investment Report 2015 (WIR). Chapter III of the report provides some new and most interesting numbers on investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS) cases—who wins how many cases and when. [1]

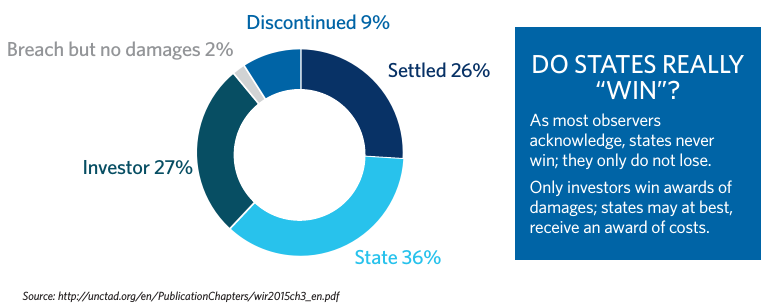

Following UNCTAD’s traditional methodology, the total number of concluded cases is broken down between settled, state “wins,” and investor wins. Arbitral decisions on jurisdiction and merits are thus cumulated without distinction. The application of this methodology results in the following numbers, also presented in the latest WIR:

Based only on the annual numbers resulting from UNCTAD’s traditional methodology, many proponents of the system have argued that investor–state arbitration or international investment agreements in general are not biased against states because the United Nations’ own numbers show that states win more than investors do. Supporters of the system have insisted on this simplistic argument to counter concerns that the system is biased against states.

But what happens when the decisions on jurisdiction and the merits are disaggregated? Looking only at the cases determined based on final arbitral awards, the number of cases leading to final awards is 255 based on the UNCTAD numbers: 144 in favour of states plus 111 in favour of investors (p. 116).

It turns out that 71 of these decisions (p. 116) for the state were decisions on jurisdiction that terminated the arbitration. Assuming that all arbitrations face some form of jurisdictional challenge—which is almost certainly true and in any event close enough to use as an assumption for present purposes—out of 255 total jurisdictional decisions, states have won 71, or 28 per cent. Investors, therefore, have won 72 per cent of jurisdictional determinations.

Taking out the 71 jurisdictional decisions that terminated arbitrations, the number of cases decided on the merits is 184. Of these, investors have won 111, or 60 per cent. Investors, thus, have won 60 per cent of the decisions on the merits.

So despite the oft-heard refrain that “states ‘win’ more often than they lose,” it is the investors that have actually won most of the time: 72 per cent of the decisions on jurisdiction, and 60 per cent of cases decided on the merits.

Why does this distinction between jurisdiction and merits matter?

Essentially, the jurisdictional phase is the point of entry: if it is relatively easy to get to the merits phase, it is more often than not worth a shot for investors, even if the jurisdiction is unclear. The high win rates for investors here show the entry point is not the most significant hurdle. By contrast, if the win rate on the merits is high—at 60 per cent here—it can lead investors to take the chance at jurisdiction even if the case may be weak on that issue.

The combination of low bars to entry and high win rates, precisely as seen here, is perfect for motivating investors, counsel and third-party funders to initiate cases. Importantly, it also increases the effectiveness of threats by investors against states in response to potential measures states may be considering adopting— the regulatory chill impact of the investor–state arbitration system.

By aggregating the numbers on jurisdiction and merits, as UNCTAD’s methodology used to do, the crucial differences between their functions and roles were lost, and the critical statistic on wins on the merits, hidden. By including additional numbers that correct for this methodological flaw, UNCTAD has now brought to light the real numbers. No longer can it simply be said that the system is balanced because states win more than investors; they clearly do not when comparing the proper numbers.

The balance in the ISDS system cannot be measured by wins and losses alone. The impacts of the current dominant approach to investment treaties and ISDS go well beyond simply a tally of wins and losses. But with these new numbers, at least it can no longer be said, simplistically, that the system is balanced because states win more than investors—they clearly do not when comparing the proper numbers.

Footnotes:

[1] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2015). Recent policy developments and key Issues. In World investment report 2015 (pp. 102–118). Retrieved from http://unctad.org/en/PublicationChapters/wir2015ch3_en.pdf