Multinational corporations and COVID-19: Intellectual property rights vs. human rights

All the versions of this article: [English] [français]

Socialist Project | 1 September 2021

Multinational Corporations and COVID-19: Intellectual property rights vs. human rights

by Peter Rossman

The multilateral trading system anchored by the WTO is not confined to cross-border trade in physical goods. It was also designed to protect corporate knowledge monopolies. Developing countries were told that strict adherence to the rules of ‘free trade’, codified and enforced by the WTO, would enhance their productive capacity through technology transfer and upskilling. The COVID-19 crisis tells a different story. The global distribution of patent-protected knowledge is highly skewed along the North/South axis reflected in the geography of vaccine production and vaccination rates.

Eighty-five per cent of vaccinations to date have been in wealthier countries, where COVID death rates have dropped dramatically. But at the current rhythm, it would take decades, not years, for people in low-income countries to be fully vaccinated.

Surpluses and untapped productive capacity amid desperate shortages are characteristic of the global order. But the vaccination gap is shocking even by comparison with, say, the hideously unequal access to the world’s food resources.

Two things are essential to close the gap and accelerate mass vaccination: full utilization of existing capacity and expanded vaccine production in developing countries. This requires loosening the vaccine makers’ grip on the monopoly of knowledge and technology embodied in their manufacture: the companies intellectual property rights (IPR). This knowledge is embodied in patents and other forms of intellectual property which allow their owners to determine who produces and sells the product, on what terms and when.

When governments funded vaccine development, they refused to condition their support on open access to the results. By choice, they invested the vaccine makers with exclusive rights to their production, pricing and distribution. Limited supplies sustain a sellers’ market in which, for example, Pfizer’s price of $19.50 per dose brings a profit margin estimated at 60-80%. In a February 2021 call with investors, the company’s Chief Financial Officer called this “pandemic pricing” and said the company expected ‘to get more on price’ post-pandemic.

Intellectual Property Rights, the WTO and TRIPS

The global rules governing IPR are set out in the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). To understand how and why globally enforceable intellectual property rights were brought into the WTO’s ‘free trade’ regime, an explanation is needed. We also need to take a look at the pharmaceutical industry, how its leading corporations have built global value chains built on IPR and what it means for public health.

TRIPS requires all member states “to make patents available for any inventions, whether products or processes, in all fields of technology without discrimination,” and sets 20 years as the minimum period for patent protection. For the life of the patent the owner retains the right to manufacture, distribute and import the product. It also provides specific protection for copyrights, trademarks, industrial designs, and “undisclosed information,” (generally known as trade secrets) and test data (like the results of clinical vaccine trials). All are relevant in the COVID-19 crisis.

Prior to TRIPS, enforcement of these rights was patchy and difficult outside national jurisdictions. Some countries provided no protection for pharmaceuticals. Others, like India, protected pharmaceutical production processes but not the products themselves, making it possible to reverse engineer a product to produce low-cost generics.

In the late 1970s, against a background of accelerating industrial production in Asia and Latin America and a worsening trade deficit, US corporations in software, pharmaceuticals and the media and entertainment sectors launched an orchestrated message of alarm: the country was losing its competitive edge and capacity for innovation due to widespread ‘theft’ of American knowhow.

Their great ‘innovation’ was to organize and lobby to bring IPR protection into trade agreements. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) had been the venue for reducing tariffs and quotas. New model trade agreements would increasingly focus on strengthening the rights of transnational investors vis-à-vis governments. Stronger IPR was one of the key objectives.

Countries hosting real or imagined competitors were threatened with loss of market access and disciplined through unilateral action. Bilateral agreements were negotiated to strengthen US companies’ IPR, followed by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the US, Canada and Mexico. Europe and Japan were brought on board.

TRIPS was unanimously adopted at the conclusion of the GATT final round in 1994 and came into effect in 1995 with the birth of the WTO. TRIPS was accompanied by another of the WTO’s foundational treaties, the Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMS). TRIMS essentially curtailed measures to promote local content and technology transfer – essential for the development of national industrial policies, like, for example, the development of national pharmaceutical industries. Countries like Brazil and India developed their pharmaceutical industries before the introduction of binding global IPR rules. TRIPS and TRIMS erected barriers to that development path.

Since TRIPS, the EU, US and other wealthy countries have returned to negotiating bilateral agreements which provide even stricter IPR protection than the ‘minimum standards’ set out in TRIPS: they are ‘TRIPS plus’.

IPR and the Pharmaceutical Industry

Intellectual property rights decisively shaped the evolution of the pharmaceutical industry and its value chain. Strict control of patents enabled the companies to limit supply and maintain monopoly prices at home and abroad.

These were vertically-integrated manufacturing companies which maintained in-house research and clinical trial departments. In the 1970s they increasingly turned to outsourcing in search of lower costs and looser environmental regulations, contracting out R&D, testing and manufacturing. The value chain became wider still as rapid advances in genetic engineering and biotechnology, powered by publicly-funded research, increasingly focused on biologics – the development of drugs based on biological rather than chemical processes. Startups and patent applications boomed, fueling competition between the pharma giants to acquire companies, large or small, with potentially lucrative patents under development. The widening value chain intensified the need for stricter IPR to prevent knowledge from leaking. [1]

In 1980, the United States passed legislation which authorized small businesses and universities to patent inventions developed with public funding. Previously these had automatically reverted to the government, which licensed them to generic manufacturers, or were injected directly into the public domain. Universities and startups were now integrated into a corporate-driven knowledge complex. ‘Technology transfer’ transformed public research into private patents.

Financializing Knowledge

At the same time the companies increasingly financialized, reducing expenditure on production capacity, employees and even R&D to free up cash to distribute to shareholders as dividends and share buybacks. [2] For two of the largest, Pfizer and Johnson and Johnson, spending on buybacks and dividends between 2006-2015 exceeded their total net income; they turned to the loan market to finance rising returns to investors and top management using their IP assets as collateral. During this period, Pfizer returned $139-billion to shareholders while spending 82 billion on R&D. [3] European companies followed, arguing, like their US counterparts that high drug prices were needed to sustain ‘innovation’.

Financialized pharmaceutical companies are best understood as organizations which manage operations as a bundle of financial rather than physical assets. Their greatest financial asset is the patents which generate 80% of their profits; competition drives a struggle for what the industry calls patent ‘blockbusters’. The ultimate blockbuster is a prescription drug, taken daily for the life of the patient, heavily marketed in a country where regulatory authorities have little capacity to negotiate on price – like the United States, by far the world’s largest pharmaceutical market. Pfizer’s cholesterol-reducing Lipitor, the all-time bestselling prescription medication, brought in $125-billion over the life of the patent and in some years nearly a quarter of the company’s total revenue. If a product takes off, companies can expand production through additional subcontracting while retaining full control.

This explains the vanishingly low level of corporate interest in, for example, treatments for tropical diseases and tuberculosis, major killers which primarily afflict the poor.

In the early 2000s, Canada’s Public Health Agency developed the first approved Ebola vaccine. There was no commercial interest prior to the West African outbreak of 2014. Today the vaccine belongs to Merck. But “It was the public sector, not Merck, that provided all of the financing, including for clinical trials, during the West African epidemic, in addition to providing the technical expertise, human resources, and infrastructure that was necessary to carry out the trials.”

The pharmaceutical industry is a highly efficient financial machine for generating income streams to investors through monopoly pricing, strict control over supplies and narrowly focused research. For all its considerable technological achievements, the industry’s patent-driven business model and financial dynamic cannot meet the needs arising from a global health emergency. Government funding made vaccines available in record time; governments hold the key to unlocking production.

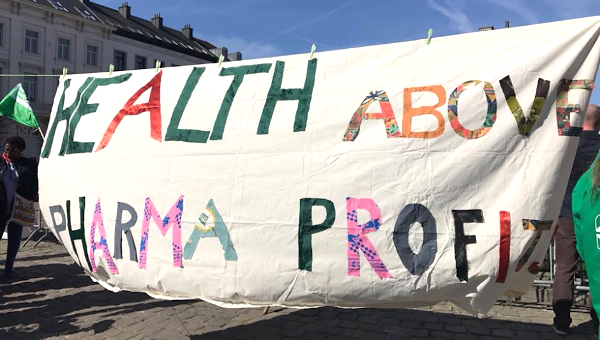

Human Rights vs. Intellectual Property Rights

In 1997, South Africa modified its patent law to facilitate access to cheaper generic treatments for HIV/Aids. The following year, 39 mostly multinational drug companies sued the government to force it to drop a law which, the lawsuit alleged, ‘deprives owners of intellectual property in respect of pharmaceutical products’. Then-president Nelson Mandela was personally named as a defendant.

The US and the European Commission supported the lawsuit. Organized resistance forced the companies to drop the suit and governments to withdraw their support for it.

Following this successful struggle for access to life-saving medicines, the TRIPS rules were ‘clarified’ in 2001 to specify the conditions under which governments facing a ‘national health emergency’ could issue compulsory licenses to manufacture without the approval of the rights holders. The procedure is cumbersome and can only proceed on a product-by-product basis, country by country. Bilateral trade agreements may further limit governments from using compulsory licensing.

The pandemic by definition is global. And intellectual property rules also protect diagnostics, treatments and personal protective equipment, all of them in short supply. Tight control of patents has held back production and distribution.

This is why 62 countries led by India and South Africa have proposed that the WTO waive member states’ obligations under the TRIPS applying to all products needed for the prevention, containment and treatment of COVID-19. The Biden administration has expressed support for a waiver on vaccines (only), but the proposal remains blocked at the WTO despite the support of two-thirds of the member states. This is not entirely the work of corporate lobbyists, though they are busy. It is a widespread article of faith that IPR must never be breached.

COVAX, governments’ and companies’ preferred vehicle for distributing vaccines to lower income countries, is essentially a philanthropic public-private partnership which leaves the companies in control of their power over production, pricing and destination. It has failed to deliver. According to its website, as of July 19, 2021 only some 129 million vaccine doses had been shipped.

In May 2020, in response to a call for global solidarity led by Costa Rica, the United Nations’ World Health Organization (WHO) launched the COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP) to boost the supply of Covid-19 diagnostics, treatments, vaccines and other products by sharing intellectual property through non-exclusive licensing agreements with qualified manufacturers. Unsurprisingly, not a single company has signed up, but it has member state support. Housed within the United Nations’ system, C-TAP could bring unused capacity online and channel investment and technology to developing countries to boost wider manufacturing. For this to happen, one, or a group of countries, home to companies with critical COVID-related IPR would have to come on board. They need to be pushed.

The primary obstacles to expanded vaccine production are political. It is hardly surprising that pharmaceutical companies and their lobbyists would fiercely oppose a COVID-19 TRIPS waiver. In a March 5, 2021 letter to the Biden administration, leading pharmaceutical companies present in the United States claimed that “Intellectual property protections have been essential not only to speed the research and development of new treatments and vaccines, but also to facilitate sharing of technology and information to scale up vaccine manufacturing to meet global needs (my emphasis). Eliminating those protections would undermine the global response to the pandemic…” The same arguments have been recycled in the EU communications to the WTO TRIPS Council opposing the waiver proposal. [4] Against all evidence, the argument is made that IPR enforcement is the solution and not the barrier to mass vaccination.

A broad corporate consensus underpins the commitment to TRIPS. Transnational companies today rely more than ever on IPR to structure their global value chains. [5] Through COVAX, the Gates Foundation has played an outsized role in the pandemic even though Microsoft holds no COVID-related patents – copyrighted software is the source of its power. There are numerous guardians of the IPR fortress.

And the IPR consensus is widely diffused. Following the 2001 Doha Declaration which was the WTO’s response to the fight for affordable access to HIV/Aids treatment, sixteen years of negotiation were needed to amend the key TRIPS article dealing with imports of generic medicines produced under compulsory license. Thirty-seven high income countries, including Australia, Canada, Iceland, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union then declared themselves formally ‘ineligible’ for such imports, even in a national emergency. This unquestioning devotion to IPR at all costs amounts to a national suicide pact, and can aptly be described as IPR fundamentalism.

Access to medicines is recognized as an essential element of the human right to health. Unions have backed the call for a TRIPS waiver. Organized action at all levels will determine which will prevail: human rights or intellectual property rights. •

Further reading:

- Long, Strange TRIPS: The Grubby History of How Vaccines Became Intellectual Property explains how US multinationals including the pharmaceutical industry built the foundations and piloted the development of what would become TRIPS.

- A well-researched and engagingly written book length study, Information Feudalism by Peter Drahos with John Braithwaite (2002), tells the full story.

- Knowledge Technology International has been documenting the role of IPR during COVID-19 through research and blogs.

- The IUF’s Trade Deals that Threaten Democracy explains how investment treaties have been layered onto the WTO rules to promote the power of transnational investors vis-à-vis governments, including through stricter intellectual property rights. Also available in French, German, Spanish and Swedish.

- Financialization: New routes to profit, new challenges for trade unions, by Peter Rossman and Gerard Greenfield, published by the ILO’s Labour Education in 2006, explains the general background to the developments in the pharmaceutical sector documented in the article by Lazonick et al. cited in this paper.

- Intellectual Monopoly in Global Value Chains by Cédric Durand and William Milberg analyzes the role of IPR in organizing value chains and how this control structures international revenue flows and global development.

An earlier version of this article first published on the Global Labour Column website.

Peter Rossman was the Director of Campaigns and Communication for the International Union of Food, Agricultural, Hotel, Restaurant, Catering, Tobacco and Allied Workers’ Associations (IUF) from 1991 until retirement in 2020.

Footnotes:

[1] On July 21, 2021 Pfizer announced that it would be producing vaccine together with South Africa’s Biovac for distribution to African countries. But, the New York Times reported, “The South African producer, Biovac, will only be handling distribution and “fill-finish” — the final phase of the manufacturing process, during which the vaccine is placed in vials and packaged for shipping. It will rely on Pfizer facilities in Europe to make the vaccine substance and ship it to its Cape Town facility.” This is the system of global IPR-based rent extraction pioneered by The Coca-Cola Company. Coke makes the concentrate, licensed bottlers do the “fill-finish.”

[2] Share buybacks reduce the number of shares in circulation, increasing earnings per share. Buybacks boost executive compensation, whose primary component is share options. Between 2006-2015, the 18 largest US pharmaceutical companies distributed 99 per cent of their profits to shareholders, half of it as buybacks.

[3] All figures from Lazonick et al. US Pharma’s Financialized Business Model.

[4] See e.g. the June 29, 2021 analysis by Médecins sans frontières.

[5] Cogently demonstrated in Intellectual Monopoly in Global Value Chains by Cédric Durand and William Milberg cited under Further Reading.