The secret business plan that could spell the end for SMEs

SME Insider | 12 Feb 15

The secret business plan that could spell the end for SMEs

Lindsey Kennedy

If it goes through, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) will have the most far-ranging impact on UK companies since the creation of the European Union. But, while the benefits to big business are clear, SMEs seem set to lose out.

Despite its extensive implications, TTIP has generated relatively little coverage, not least because negotiations are shrouded in secrecy and conducted primarily with corporate lobbyists, who have minimal obligations to the public interest. So clandestine are the talks that the few MEPs that are granted access can only view the plans in their original documentation, in a secure location, with the threat of espionage charges if they try to make copies or share the details with the public.

Little wonder, then, that civil rights groups and democracy campaigners are jittery – or that large-scale protests, campaigns and marches are emerging everywhere from London to Ljubljana, and from Brussels to Berlin.

With little definite information to go on, much of the argument on the left has been pitched as an apocalyptic struggle between individual freedom and corporate evil, while the right frantically attempts to dismiss even the mildest concerns as Luddite meddling that will reduce Britain to a provincial cousin pawing at China’s door. Between these two extremes, it’s hard to get a clear idea of what a post-TTIP world would look like at all.

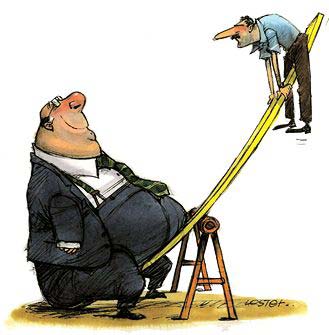

What both sides do agree on is that this is a proposal designed to serve the needs of business. But here’s where it gets tricky: what kind of business are we talking about? TTIP’s free trade leanings have clear appeal for corporations, but would there be any benefit to an SME?

“Certainly one of the key aims is to create a free market on both sides of the Atlantic,” says John Hilary, Director of War on Want, and one of the most outspoken critics of TTIP. “It’s not about the US versus the EU, it’s about big business versus small. The idea is to remove regulations… but many of these are in favour of SMEs”.

In countries with the highest concentration of small and family-owned businesses, such as Italy and France, people are “absolutely petrified”, he says, while the German Mittelstand (the country’s mostly family-run SME sector), which represents 99% of firms in the country, is adamantly opposed to the plans.

“The idea that this is going to improve competition for small business is nonsense,” adds Hilary. “We know that when you remove regulations like this, you get more concentration of capital and corporations start sneaking up and taking over markets.”

Given the risks, you might expect serious economic gains on the horizon, but a glance at the best case scenarios for exporting and economic growth are, for a start, underwhelming. The European Commission’s Centre for Economic Policy Research, a major advocate of TTIP, has said that the agreement will boost EU economic output by 0.5% by 2027. Export predictions are slightly more positive, with the most optimistic among them putting growth at 5-10% over a 10-20 year period, but given the rapid rate of growth among SMEs even without such an agreement in place, it’s hard to see why such a potentially disruptive move is a necessary intervention.

More worrying is how these benefits, limited though they are, will be brought about. Since tariff rates between the US and the EU are, at around 3%, already extremely low, it’s not actually trade arrangements that would be targeted by the new rules. Instead, it is regulations, most of which have been put in place to protect people, the environment and – yes – small business, and most of which are in the EU.

To a large extent, the US is able to produce cheaper goods than Europe because its companies are bound by fewer rules. Labour protections are minimal compared to those in its EU counterparts, wages are low for a developed country and, whereas Europe has strict rules over the substances you can put in things like food and skincare products, the US is comparatively lax. The so-called “harmonisation” of these rules will almost certainly mean dropping European standards to accommodate American ones. And, whatever you think of the ethics of this, the business case – for SMEs, at least – is weak.

If you’re a small business in Europe that creates products adhering to long-running EU rules, your products are probably going to be more expensive to produce than their US equivalents, which can make greater use of cheap labour as well as, potentially, questionable chemicals and practices. If many of the EU’s regulations are scrapped, many of these cheap US products that were previously banned on the continent are likely to flood in, undercutting your prices.

You may be able to overhaul your production processes, at considerable expense to your business, in order to drive down prices. However, despite the weakening of workers’ rights that has taken place in the UK over the past few years, it will take far longer to change European cultures so significantly that employees will be willing to accept the reduced standards that workers in the US are used to. If anti-immigration rhetoric continues to escalate in Britain, most of which is focussed on low-pay, unskilled workers, the problems will only intensify.

On the other hand, if you’re a large-scale company that has either already outsourced production or can do so relatively easily, TTIP could give your business a boost – but at considerable advantage over your smaller competitors.

A second serious consideration for SMEs is the damage that TTIP could do to local and home-grown businesses. In the US, for example, the Buy American Act gives preferential treatment to US-made products – but the EU is pushing for this to be eliminated as a basic tenet of TTIP.

Meanwhile, in the UK, many local councils have implemented schemes that aim to strengthen communities and support small businesses by prioritising relationships with local suppliers. The UK government recently pledged support to smaller businesses by setting a target for 25% of its supplier contracts to be fulfilled by SMEs by May 2015. From the information available at present, it seems that both of these arrangements would be deemed illegal under TTIP, which would prevent organisations from adopting a prejudicial stance against global corporations.

In doing so, these kinds of clauses not only interfere with the country-specific policy decisions of democratically elected governments, as many anti-TTIP campaigners have pointed out. More pertinently for small business, they would also deal a serious blow to the competitive landscape, and to the growth prospects of SMEs.

In fact, one of the most alarming aspects of the TTIP plans is its inclusion of an investor-state-dispute-settlement provision (ISDS) – essentially secret courts that allow companies to sue governments if they do things that hurt corporate profits. This, certainly, is not a theoretical issue. ISDS clauses have been included in trade agreements before, with serious financial consequences for governments; in 2012 alone, 244 cases were settled and 58 new ones brought against sovereign governments by private companies, nearly 60% of which resulted in a win by the company or a settlement by the government.

In one of the most controversial cases, the cigarette company Philip Morris is currently in the process of suing Australia and Uruguay over their respective decisions to alter cigarette packaging to help deter smoking – and it is believed that the proceedings played a major part in New Zealand’s plan to drop similar measures. If government health policy can so easily be dictated by the financial interests of multinationals, it seems likely that attempts to limit monopolies by supporting SMEs will, too, be consigned swiftly to the scrapheap.

Having been faced with near-unilateral public disapproval over ISDS, TTIP proponents have recently begun to suggest that the plans (which are now, it seems, too embedded to simply drop from the agreement) could actually be used to benefit SMEs, based on the idea that they could use the clause to protect their interests. But, when the basic legal costs run into the millions of dollars, it seems highly unlikely that any small business would be able to consider this route.

Hilary is more blunt. “These arguments have been constructed without any economic literacy whatsoever,” he says. “SMEs are saying: don’t be ridiculous.”

Indeed, it’s hard to find any pockets of enthusiasm for the plans among small businesses or their representatives. In its tentatively offered support for TTIP, the Federation for Small Businesses has said that the “huge potential” offered by the agreement is entirely dependent on it introducing specific protections for small businesses – a first-of-its-kind “Small Business Charter”, to be precise. This, as far as we know, is yet to materialise – and many FSB members are privately skeptical about their role in the negotiations. Unless it does adapt to include major protections for small business, TTIP remains emphatically a vehicle for big business to widen their reach and lessen their responsibilities. The benefits to SMEs, if any, are negligible. The risks are catastrophic.