The Donald Trump effect: India faces prospect of integrating deeper with Asia-Pacific if RCEP expands into FTAAP

Financial Express | 25 November 2016

The Donald Trump effect: India faces prospect of integrating deeper with Asia-Pacific if RCEP expands into FTAAP

By Amitendu Palit

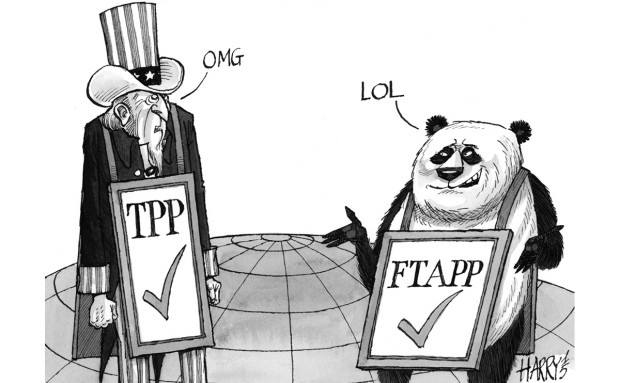

The Donald Trump effect on the Asia-Pacific has become pronounced sooner than expected. While outgoing US president Barack Obama and the rest of the TPP-member-country heads pledged their support to the agreement at the APEC meeting in Lima, Trump announced his intention to withdraw the US from the TPP as one of his top priorities. The announcement confirmed the worst fears of the non-US TPP members. As the region reconciles to the imminence of the US withdrawal from the TPP, several scenarios emerge.

There is a possibility of the TPP going ahead without the US. A non-US TPP would hardly command as much influence in economic and strategic terms as it would have with the US. Apart from a sharp reduction in economic size, the TPP would lose its strength as a geo-strategic alliance in the region. Nonetheless, it could still get going without the US. The current TPP agreement requires at least six members accounting for a minimum of 85% of the bloc’s total GDP to ratify the deal for making it functional. This makes it impossible for the TPP to take off without the US, which accounts for 60 per cent of the bloc GDP. The arithmetic would change if the US pulls out. It would then come down to Japan and other large economies of the bloc, notably Australia and Canada, to ratify the deal for getting it going. While the TPP has faced opposition in several of its members, none, apart from the US, are significantly concerned over its domestic ratification, with New Zealand having already done the needful. The possibility of the non-US TPP members going ahead with the deal cannot be overlooked given that they would hate to see years of negotiations on the TPP go to waste. However, the agreement could well come for up a review with many members wanting to scale back concessions that they had made specifically for the US. The provisions on investment rules, state-owned enterprises, intellectual property protection for biologics, labour standards and environment could be the ones up for further review.

It would be erroneous to assume that Donald Trump, while withdrawing the US from the TPP and aiming to renegotiate the NAFTA, would entirely turn his back on trade. His intention appears to be to work on bilateral FTAs as opposed to big RTAs. These FTAs can extend to the Asia-Pacific and might include TPP members as well. The US already has FTAs with several TPP members like Australia, Canada, Chile, Mexico, Peru and Singapore. The TPP would have given it preferential access to countries with which it doesn’t have FTAs—Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand and Vietnam. By entering into bilateral FTAs with some of these countries, the US can hope to have good trade deals fashioned according to its specific interests and advantages with respect to each country. Trump’s assessment clearly is that such deals are better for the US than a humongous TPP that while getting a lot for some US businesses doesn’t produce win-win outcomes for all and can put the US into trouble from overarching obligations like enabling non-US TPP member country businesses to arbitrate against the US.

A prominent scenario in the region is the emergence of the RCEP as the next best alternative for regional economic integration. Many analysts are interpreting this as a strategic victory for China. While China would be happy over the US withdrawal from the TPP, it may not be able to steer RCEP as close to its trade and strategic agenda as it wishes. It does not have as much strategic leverage over the RCEP members as the US had in the TPP. Nevertheless, as the largest economy in the RCEP and the second-largest economy of the Asia-Pacific and the world after the US, China is in a position to influence RCEP talks. A major relief for China at this juncture is avoiding the uncomfortable prospect of dealing with a trans-Pacific trade deal in the Asia-Pacific that would have had rules written by the US. China has capitalised the Trump victory and US withdrawal from the TPP by reviving the demand for a Free Trade Area in the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) to be based on the RCEP. This makes it the champion for expanding the size and scope of the current RCEP from an Asia-centric, ASEAN+ architecture to an agreement spanning both sides of the Pacific. With non-US and Asian TPP members—Australia, Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, New Zealand, Brunei and Vietnam—pinning hopes on the RCEP for achieving at least a part of what the TPP had aspired to, the RCEP is the deal that the region is watching out for.

As a major non-APEC member of the RCEP, India faces the prospect of integrating deeper with the Asia-Pacific if the RCEP expands into the FTAAP. The development would make India a part of the Asia-Pacific trade regulatory framework in spite of not being a member of the APEC. Belonging to the FTAAP might make the requirement of being a formal member of the APEC less significant for India since it would, as it is be able to contribute to regional trade rule making through the FTAAP. From a long-term perspective, it makes sense for India to bat for lifting RCEP to FTAAP.

The author is senior research fellow and research lead (trade and economic policy) at the Institute of South Asian Studies in the National University of Singapore. E-mail: isasap@nus.edu.sg