Asia-Pacific women groups gather in Bangkok and discuss digital trade

All the versions of this article: [English] [Español] [français]

bilaterals.org - 04 October 2022

Asia-Pacific women groups gather in Bangkok and discuss digital trade

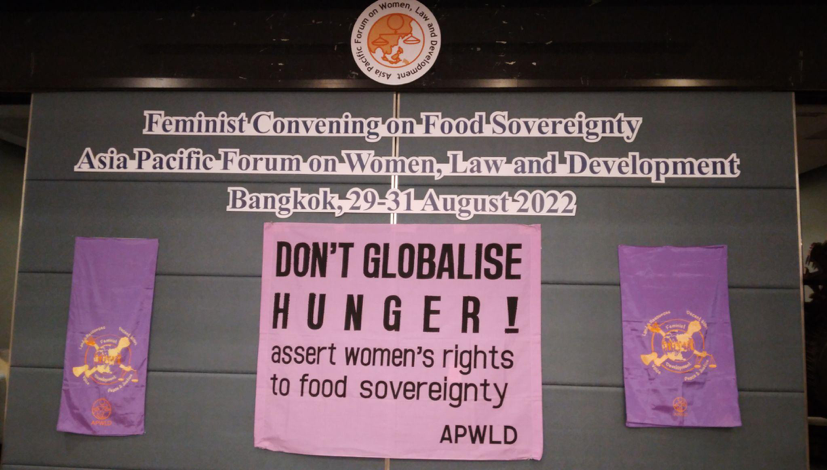

On August 29-31, 2022, Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development’s (APWLD) Feminist Food Sovereignty Convening in Bangkok, Thailand brought together APWLD members, partners and allies from the Asia Pacific region. A panel discussed the issue of digitalisation and free trade agreements (FTAs), connecting it to corporate hegemony and the impacts on the condition of women. Arieska Kurniawaty from Solidaritas Perempuan, Indonesia, facilitated the discussion between Elenita Dano (Action Group on Erosion, Technology and Concentration or ETC Group) and Kartini Samon (GRAIN).

Bilateral free trade and investment agreements in force today are notable in their comprehensiveness and range. They typically cover an expansive range of issues, which multiplies their impacts across societies and sectors, then generating widespread resistance against them in many countries. Digitalisation has been one of the key emerging issues in the many recent bilateral free trade and investment agreements’ negotiations.

Trade liberalization and FTAs have their roots in the lengthy history of colonial exploitation. The purpose today is the same as it was in the traditional colonial states, which were designed for the extraction of natural resources. Under the pressure of globalisation, nations are compelled to serve as a source corporate plunder, and FTAs are a powerful tool for corporations. The “mega regional” trade deals grant a lot of rights to those corporations. Investor state dispute settlement (ISDS), for instance, which is often included in FTAs, imposes restrictions on what governments are allowed to do or not allowed to do. Governments can be sued for any policy decision which negatively impacts the expected profits of corporations.

“Who decides the clauses in these trade agreements?” Kartini Samon notes. “It is the hands of corporations. Corporations are often involved in drafting the clauses in trade deals. The objective is to form a continuous link between governments and corporations, and force the acceptance of binding rules.”

Of course, women in particular have been affected disproportionately. For example, there is still a societal expectation in many places for women to put food on the table. When there is an obstacle that prevents this, we see a boost in violence in the household, even when the situation is out of their control. In traditional farming, women maintain the practices of seed saving and preserving food. These practices are all affected when traditional systems are disrupted. We have seen multiple food crises during the peak era of trade deals. Lobbying for fair FTAs is not going to get us out of the mess - it is just a distraction to the real solutions.

Samon highlighted that during the COVID pandemic - when food supplies could not be delivered and borders were closed - we saw that it is possible to have a different way to trade food. Communities demonstrated their ability to make sure that everyone gets food on the table despite the fact that free trade was not even an option. The Landless Workers Movement in Brazil (MST) were able to send 600 tons of fresh produce to 24 states in the country. In Indonesia, fisher and farmer communities came together to barter and get complete meals on their table.

Meanwhile, corporate power continues to increase its hegemony. Large corporations, technology companies, agribusiness and banks are hugely investing in food and agriculture. Elenita Dano from ETC Group has studied precision farming for 20 years. Digital tools are important for precision farming. The assumption is that farmers make a lot of mistakes, indigenous knowledge has a lot of gaps, but machines are precise and reliable. That’s why digital tools are needed. The North has been saturated with all of these digital tools for the past 20 years, and now they need somewhere else to expand the market. That somewhere is the Global South. Digital tools are being used for imperialist expansion and technology has created even more inequalities.

In the Philippines banana plantations, farmers are now using drones instead of planes to spray fertilizer because they address drifting (low flying), are less prone to accidents (smaller), and are more precise (better aim). However, these drones ultimately increase the use of chemicals in farming. The COVID pandemic was another driver of digitalisation, populations became dependent on e-deliveries. Hence farmers had to become better linked to online markets.

According to a recent ETC study, the centralisation of power has been greatly aided by digitization. Six corporations used to monopolize the seed market, but today only four companies are in charge of around 65% of all commercial seeds sold worldwide and nearly 75% of all agrichemicals. Many large banks and other corporations have investments in all four corporations as well. They use blockchain to streamline processes. Additionally, it enables them to work together and determine prices. Under this system, competition is a thing of the past. For instance, Amazon acquired Whole Foods in 2017 and has since emerged as a major retailer of groceries.

The clouds of big tech companies, such as Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, are where the data is stored. What exactly are these "clouds"? They are actual structures located in remote areas of the world – often in the US. They’re also strongly linked to conflicts, as they need minerals like cobalt and nickel to operate their equipment For instance, a conflict has been raging in Congo for over 20 years, in relation to the extraction of raw resources.

The real producers who feed 70% of the world are peasants, small farmers and fishers. They should reclaim this. These communities need to be the ones making the decisions on what digital technologies work for them; what they want to use; and what they can control. Corporations talk about bringing digitalisation to the whole world when mechanisation has not even reached some places yet. Digitalisation is not necessary. “Do we really need it?” Dano asks. Will it really respond to our current needs? We do not have to surrender to it, like big business wants to make us believe.