Foreign Direct Investment: myths and realities

IPS | 20 December 2015

Foreign Direct Investment: myths and realities

by Yilmaz Akyüz, chief economist of the South Centre

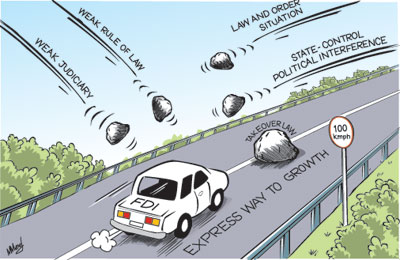

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is perhaps one of the most ambiguous and the least understood concepts in international economics. Common debate on FDI is confounded by several myths regarding its nature and impact on capital accumulation, technological progress, industrialization and growth in emerging and developing economies.

It is often portrayed as a long term, stable, cross-border flow of capital that adds to productive capacity, helps meet balance-of-payments shortfalls, transfers technology and management skills, and links domestic firms with wider global markets.

However, none of these is an intrinsic quality of FDI. First, FDI is more about transfer and exercise of control than movement of capital. Contrary to widespread perception, it does not always involve flows of financial capital (movements of funds through foreign exchange markets) or real capital (imports of machinery and equipment for the installation of productive capacity). A large proportion of FDI does not entail cross-border capital flows but is financed from incomes generated on the existing stock of investment in host countries. Equity and loans from parent companies account for a relatively small part of recorded FDI and even a smaller part of total foreign assets controlled by transnational corporations.

Second, only the so-called greenfield investment makes a direct contribution to productive capacity and involves cross-border movement of capital goods. But it is not easy to identify from reported statistics what proportion of FDI consists of such investment as opposed to transfer of ownership of existing firms (mergers and acquisitions). Furthermore, even when FDI is in bricks and mortar, it may not add to aggregate gross fixed capital formation because it may crowd out domestic investors.

Third, what is commonly known and reported as FDI may contain speculative components and creates destabilizing impulses, including those due to the operation of transnational banks in host countries, which need to be controlled and managed as any other form of international capital flows.

Fourth, the immediate contribution of FDI to balance-of-payments may be positive, since it is only partly absorbed by imports of capital goods required to install production capacity. But its longer-term impact is often negative because of high import content of foreign firms and profit remittances. This is true even in countries highly successful in attracting export-oriented FDI.

Finally, superior technology and management skills of transnational corporations create an opportunity for the diffusion of technology and ideas. However, the competitive advantage these firms have over newcomers in developing countries can also drive them out of business. They can help integrate developing countries into global production networks, but participation in such networks also carries the risk of getting locked into low value-added activities.

These do not mean that FDI does not offer any benefits to developing and emerging countries. Rather, policy in host countries plays a key role in determining the impact of FDI in these areas. A laissez-faire approach could not yield much benefit. It may in fact do more harm than good.

Successful examples are found not necessarily among countries that attracted more FDI, but among those which used it in the context of national industrial policy designed to shape the evolution of specific industries through interventions. This means that developing countries need adequate policy space vis-à-vis FDI and transnational corporations if they are to benefit from it.

Still, the past two decades have seen a rapid liberalization of FDI regimes and erosion of policy space in emerging and developing countries vis-à-vis transnational corporations. This is partly due to the commitments undertaken in the World Trade Organization as part of the Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures .

However, many of the more serious constraints are in practice self-inflicted through unilateral liberalisation or bilateral investment treaties signed with more advanced economies – a process that appears to be going ahead with full force, with the universe of investment agreements reaching 3,262 at the end of 2014.

Unlike earlier bilateral treaties, recent agreements give significant leverage to international investors. They often include rights to establishment, the national treatment and the most favoured-nation clauses, broad definitions of investment and investors, fair and equitable treatment, protection from expropriation, free transfers of capital and prohibition of performance requirements.

Furthermore, the reach of bilateral investment treaties has extended rapidly thanks to the use of the so-called Special Purpose Entities which allow transnational corporations from countries without a bilateral treaty with the destination country to make the investment through an affiliate incorporated in a third-party state with a bilateral treaty with the destination country.

Many bilateral investment treaties include provisions that free foreign investors from the obligation of having to exhaust local legal remedies in disputes with host countries before seeking international arbitration. This, together with lack of clarity in treaty provisions, has resulted in the emergence of arbitral tribunals as lawmakers in international investment which tend to provide expansive interpretations of investment provisions in favour of investors, thereby constraining policy further and inflicting costs on host countries.

Only a few developing countries signing such bilateral treaties with advanced countries have significant outward FDI.

Therefore, in the large majority of cases there is no reciprocity in deriving benefits from the rights and protection granted to foreign investors. Rather, most developing countries sign them on expectations that they would attract more FDI by providing foreign investors guarantees and protection, thereby accelerating growth and development. However, there is no clear evidence that bilateral investment treaties have a strong impact on the direction of FDI inflows.