Future of ISDS in TTIP and beyond. Is now the time for reform ?

Lexology | 18 June 2015

Future of ISDS in TTIP and beyond. Is now the time for reform ?

Bulboaca & Asociatii SCA

Investment arbitration is perhaps one of the least explored subjects in the legal world, mostly because of the highly specialized legal training that is required to understand the complex framework in which it takes place. Due to this, investment arbitration has developed and grown at its own pace, critics would say in closed circles and surrounded by secrecy.

Nevertheless, despite its highflying character, in the past couple of years investment arbitration (investor-state dispute settlement or ISDS, as it is commonly referred to now) has been at the centre of a growing and heated debate between many players, ranging from law practitioners, politicians and NGOs to private individuals.

The purpose of this article is to provide background on the public debate surrounding ISDS and to analyse current trends and potential developments in this field.

Background. Enter TTIP.

The debate arose in the context of the ongoing negotiations that began in July 2013 between the US and the EU Commission to conclude the Transatlantic Trade Investment Partnership (TTIP). TTIP has the potential to become one of the largest trade deals ever, bringing together economies that account to over 45% of the world’s GDP by eliminating custom duties for goods, facilitating access for services providers and enhancing cooperation between regulatory authorities with the aim of ultimately providing equivalent protection and recognition across markets. TTIP would have a great impact on numerous sectors (manufacturing, agriculture, energy, infrastructure or even financial services) unlocking new opportunities for businesses and potential investors which were previously wary of entering new markets or tapping their full potential.

Since the key notion is investment, the negotiating parties thought an ISDS mechanism involving international arbitration would be the obvious choice for settling any disputes arising under TTIP. Investment arbitration had already built a stable reputation, being widely used in the dense web of roughly 3,000 investment treaties in force today (bilateral, multilateral or regional) to protect investors against expropriation or other forms of detrimental interference from host states.

Most unexpectedly however, the proposal to include ISDS in TTIP was met with fierce resistance from the public, fuelled by anti-globalization NGOs, leftist politicians within the EU Parliament (which will vote on the final draft of TTIP) or news outlets supporting these views. Voices of opposition came from countries such as Germany (the first signatory of a BIT and the country with the largest network of BITs worldwide), France and others, but gained its own momentum on the internet. Even an online petition was set up to stop these sinister trade deals (referring to TTIP and the Comprehensive Trade and Economic Agreement (CETA) negotiated between the EU and Canada), which purportedly raised 2,200,217 signatures as at the date of this article. Discussing such a complex topic while lacking relevant legal training or adequate information soon led to using phrases such as “foreign firms,” “special rights,” secretive tribunals” and “highly paid corporate lawyers” to describe ISDS. Critics eventually rallied by saying that ISDS is a unilateral mechanism that allows large foreign multinationals to sue states which adopt legislation that negatively impacts their profits, although such legislation was enacted in pursuit of legitimate public policy, and that this mechanism unjustifiably circumvents national courts systems.

The real debate. Proposals for ISDS.

Taken by surprise by the sudden opposition to ISDS, the EU Commission suspended the negotiations on TTIP and initiated a public consultation that ran from March through July 2014. The purpose of the consultation was to identify a possible approach towards including ISDS in TTIP and to obtain feedback on several proposals designed to innovate ISDS. The Commission received 149.399 submissions, which is quite impressive considering the highly specialized legal issues discussed. Also relevant is the fact that 99.62% of these submissions came from individuals and only 0.38% (569 replies) came from organizations, among which 180 NGOs, a number of companies, trade unions and others, but only 7 law firms and 8 academics.

The debate became serious when key players realized that the negative perception on ISDS jeopardized the negotiations on TTIP while also further antagonizing the public against this mechanism. Scholars, practitioners, associations and institutions from the legal profession on both sides of the Atlantic got involved in the fray, both for and against. As to the character of the debate, it is revealing to know that even the International Bar Association issued a statement correcting misconceptions and inaccurate information around the discussions on investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS).

Trying to resolve the deadlock on ISDS and TTIP, the EU Commissioner on Trade, Cecilia Malmström, released in early May a concept paper entitled Investment in TTIP and beyond – the path for reform. The paper outlines a possible approach towards resuming the negotiations on TTIP and ISDS, both of which she strongly favours. The paper also contains a number of proposals aimed at reforming ISDS in order to make it more acceptable to its opponents while also taking into account the major points of concern identified during the public consultation.

There are many reasons why these proposals are important for the future of investment arbitration. First, they serve as focal points in the negotiations to include ISDS in TTIP. Second, the EU Trade Commissioner already stated that it intends to profoundly reform investment protection and related ISDS as part of the EU’s future investment policy and this concept paper gives us an insight as to what this reform means. Thirdly, the essence of these proposals has already been incorporated in CETA so we will soon be able to see their practical impact. Lastly, in the context of this debate, some prominent scholars and practitioners have also echoed the need for certain changes and improvements to investment arbitration, which is a sign that reform is truly necessary and also acknowledged from the inside.

Below are the main points of reform which the EU considers important for future ISDS mechanisms :

– strengthening the right of states to regulate and achieve legitimate policy objectives, such as health, safety, clean environment etc.

– defining key concepts for investments, such as fair and equitable treatment and indirect expropriation to eliminate unwelcome discretion that arbitrators have in interpreting them ;

– introducing the ability of the parties to an investment agreement to adopt binding interpretations of certain provisions ; ISDS tribunals will be obliged to respect these interpretations even in on-going cases ;

– preventing “forum shopping” : only businesses with real operations in a territory will be covered by investment protection provisions ;

– imposing full and mandatory transparency of the proceedings and all documents to become publicly available ; the UNCITRAL Rules on Transparency in Treaty-based investor-State Arbitration will serve as guidance ;

– including a clear code of conduct for arbitrators to ensure full impartiality, high ethical and professional standards ; providing a clear mechanism to determine whether a conflict of interest exists or is potential and concrete steps on how to address this ;

– creating rules for the early dismissal of unfounded or frivolous claims ;

– implementing a clear “loser pays principle” in investment claims, as opposed to recent trends of arbitral tribunals to decide that the arbitration costs and expenses should be split evenly by the parties ;

– having a clear “fork-in-the-road” provision to avoid parallel proceedings and prohibit investors to seek double compensation before national courts and ISDS tribunals ;

– working towards establishing a future appeal mechanism for arbitral awards, to ensure consistency and predictability.

While these points clearly show how the EU wants to reform ISDS, the concept paper goes even further, implying that the ISDS mechanism in TTIP should also :

– enhance the rights of domestic authorities to regulate matters while clearly defining the standards in which investment protection applies ;

– have clear provisions on the granting of state aid to investors (in order to avoid situations such as the one arising in the Micula v. Romania case) ;

– have a predefined roster of arbitrators agreed by the TTIP parties from which the disputing parties can choose ; the arbitrators should possess expert knowledge of how to apply international law and could also be required to have certain qualifications (i.e. to be able to hold judicial office in their home jurisdiction) ;

– create a right to intervene in ongoing proceedings for third parties with a direct and existing interest in the outcome of a dispute, a substantial advance from the current (and only) amicus curie option ;

– have a “no u-turn” provision which will prohibit investors to resort to ISDS or national courts once a claim has been submitted in one forum ;

– contain a rendez-vous clause committing the Parties to discuss setting up an appellate mechanism in the future.

Conclusions. Future of ISDS, in TTIP and beyond

The concept paper concludes with a firm proposal to establish a permanent investment court, having an appellate mechanism and a list of tenured judges, which the EU should ultimately use to settle disputes arising out of multiple investment agreements. The authors of the concept paper also believe that the proposals should set the standard for future investment protection provisions that the EU will negotiate, as TTIP provides a unique opportunity for reforming and improving the ISDS system.

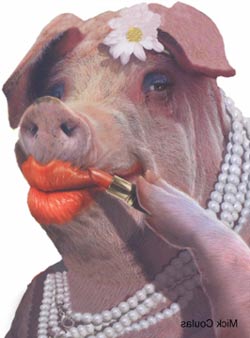

However, despite her best efforts, EU trade commissioner Malmström did not succeed in convincing the MEPs to support her proposal, with most groups still wary of ISDS. The chair of the EU Parliament’s international trade committee and rapporteur on TTIP said that the proposal was “a step in the right direction but still does not go far enough to restore public confidence” while a socialist MEP accused the commissioner of “trying to put lipstick on the ISDS pig”. And on top of this, the central idea of the proposal – the permanent investment court – gathered little support in the EU Parliament and was firmly rejected by the US.

It is unfortunate to see these reactions and the way the debate has unfolded so far. Voices from within the international arbitration community have already stated that concrete steps should be taken to improve transparency of arbitral proceedings and the independence of arbitrators. Many have also agreed that two hallmarks of investment law – secrecy in treaty negotiations and confidentiality in dispute settlements – are eroding. Moreover, there is a recent and growing trend among states to challenge and obstruct the entire arbitral process (including enforcement) arguing for their right to pass laws as part of legitimate public policy. Thus, it appears that investment arbitration already has its own problems to deal with and the recently added spotlight is certainly not helping.

The authors of this paper believe that the ongoing debate should be used as an opportunity to reform ISDS in certain areas and improve its public perception at the same time. The EU has already stated that it intends to profoundly reform ISDS and has given indications as to how it will negotiate future investment agreements and trade deals. The investment arbitration community has also acknowledged that it is time for certain changes and adjustments to take place. A consensus is clearly forming, but the main stakeholders – businesses and governments – have yet to make a clear stand. It is ironic, considering that they are the main – and only – parties in investment arbitration and that any changes to ISDS would directly impact their ability to effectively settle disputes. Perhaps a pragmatic and well-grounded approach of the key players involved in ISDS could save TTIP and future investment agreements from protracting debates, which would only hinder the main goal of these agreements – to facilitate growth through investment – but without renouncing a viable dispute resolution mechanism.

Bulboaca & Asociatii SCA - Adrian-Catalin Bulboaca and Marius Iliescu