Next steps on the USMCA corn case: What the panelists should ask

IATP | 24 June 2024

Next steps on the USMCA corn case: What the panelists should ask

by Karen Hansen-Kuhn

For original formatting (hyperlinks, tables...), view article on original page

This week the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) dispute over Mexico’s restrictions on genetically modified (GM) corn and glyphosate enters a new phase. A public hearing will be held on June 26 and 27 in Mexico to consider the arguments made by both sides. This will be the first time we’ll hear directly from the panelists who will decide the case and the last scheduled intervention before a preliminary decision is issued this fall.

As a reminder, the Mexican government announced its plans to transition away from imports of GM corn and the use of glyphosate shortly after President Andrés Manuel López Obrador took office in 2019. These plans were part of a bigger package of reforms intended to strengthen the country’s self-reliance on its food supplies and to move toward agroecological production. Those measures responded to years of concerted efforts by social movements, including successful advocacy efforts and litigation led by the Sin Maíz No Hay País (Without Corn, There Is No Country) campaign to prevent planting of GM corn and protect the country’s cultural heritage and biodiversity.

The initial decree called for phasing out the use of glyphosate and of imports of GM corn by 2024. The revised decree issued in February 2023 continues the eventual phaseout of glyphosate, eliminates the use of GM corn in flour and tortillas for direct human consumption, and calls for the eventual substitution of GM corn for industrial use and animal feed as non-GM corn becomes available.

The U.S. filed a formal dispute under USMCA on August 17, 2023, focused on what the U.S. calls the Tortilla Corn Ban and the Substitution Instruction. The U.S. asserts that the Mexican government’s actions violate Sanitary and Phytosanitary Standards (food and plant safety provisions) in the agreement, saying the decisions were not based on international standards or risk assessment principles and discriminate against U.S. exports. Even though it does not export corn to Mexico, Canada joined the complaint as a third party.

The U.S. and Mexico have each issued detailed complaints and rebuttals amounting to hundreds of pages of information and several hundred informational annexes. Ten non-governmental organizations (including IATP) from Mexico and the U.S. made submissions on the case in April. The Biotechnology Industry Organization, the world’s largest biotech industry advocacy organization, also submitted comments. The panel declined to receive comments from Canadian organizations, even though it did accept a submission by the Canadian government. IATP has posted the government and NGO responses here, along with a series of summary articles and a webinar series by civil society organizations from the three countries.

Most recently, Mexico filed its formal responses to the second round of the detailed U.S. complaint on June 19, 2024. Incoming Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, who will take office on October 1, has indicated her administration’s continued commitment to the restrictions on GM corn and to achieving greater national self-sufficiency in corn production. Now the decision is up to the three-person dispute panel. According to the official timetable (which could be revised), after the hearings this week, the panel will issue a preliminary report in September, with a final decision anticipated in November.

My colleague Tim Wise summarized the latest Mexican response to the U.S. positions. The science around the safety of GM corn is at the heart of the debate. Corn, especially white corn, is a huge part of the Mexican diet, so the potential health impacts of GM corn and the glyphosate residues could be much more significant than in countries like the U.S., where it is mainly yellow corn used as animal feed, ethanol and in processed foods. In any case, the 2023 decree only restricts the use of white corn for human consumption, not yellow corn. The U.S. Center for Food Safety has described the lax regulations in the U.S (which seemingly would be the model), pointing out that,

In 2020, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) largely deregulated GMOs, meaning for most GM crops there is no assessment of environmental risk, and no mandatory gene containment measures even at the experimental field trial stage. If companies "self-determine" that their GMOs fit into one of several large exemption categories, they don’t even have to inform USDA before growing them outdoors. Thus far, 79 GM plants have been exempted, and there could be many more. An ongoing lawsuit launched by CFS and allied food and farming groups challenges USDA’s deregulation rule.

The Mexican government offered to conduct joint research with the U.S. on the safety of GM white corn given its importance in the Mexican diet, apparently with no response. The panel will no doubt center many of its questions on the dueling notions that the U.S. standards and the science they’re based on are perfectly fine, versus the Mexican evidence from newer studies of potential harm to human health and the need for a precautionary approach.

The science around GM corn will be the centerpiece of the debate, but it’s not the only issue. The panelists should also raise questions on other crucial issues, including:

Where’s the economic harm?

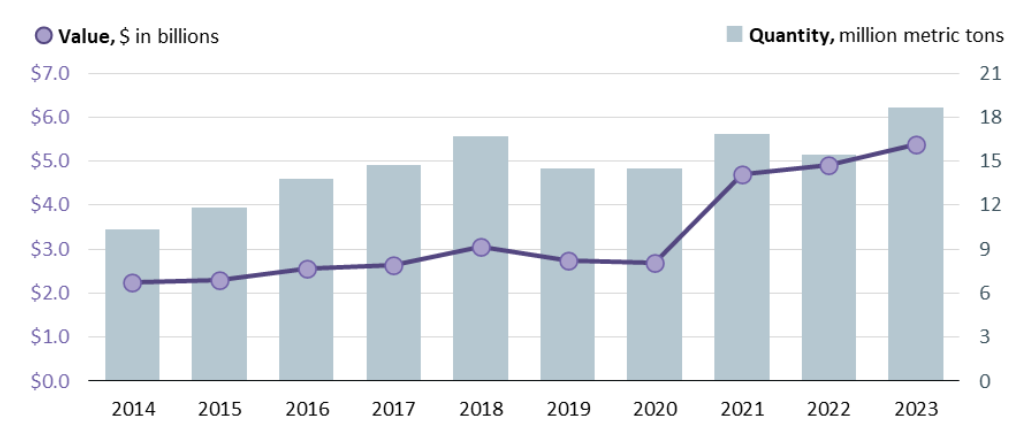

The U.S. insists that the Mexican rules on GM corn will undermine its exports. In fact, U.S. corn exports to Mexico have increased since the Decree was issued. There was a slight decrease in exports of U.S. white corn in 2022 when Mexico temporarily lifted restrictions on imports of white corn from Brazil due to a drought in Mexico. Since then, the normal tariffs were reinstated, and U.S. white and yellow corn exports have surged to higher levels this year (as indicated in this chart from a U.S. Congressional Research Service report on the dispute).

Figure 1. U.S. Corn Exports to Mexico (2014-2023)

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Trade Data via U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS), “Global Agricultural Trade System Online: GATS Home,” BICO-10, May 2024, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/default.aspx. Note: Data are not adjusted for inflation.

Keep in mind that non-GMO corn producers in the U.S. have made it clear that they are ready and willing to supply Mexico with as much non-GMO yellow or white corn as they need. So, if Mexico continues to import U.S. yellow corn, and U.S. suppliers are happy to provide non-GM white corn, what is the economic harm?

Does USMCA allow Mexico to meet its commitments to Indigenous peoples and on biodiversity?

USMCA made several important innovations in U.S. trade policy, including the establishment of a Rapid Response Mechanism for violations of labor rights and a significant weakening of Investor State Dispute Settlement (which allows corporations to sue governments over measures that affect their expected profits). Largely as a Canadian response to demands by First Nations organizations, it also includes a new provision ensuring that nothing in the trade agreement will keep a government from meeting its commitments to Indigenous people. This is binding language and creates a general exception to other provisions in the agreement. As we explained in our submission with the Rural Coalition and the Alianza Nacional de Campesinas, Article 32.5 builds on similar language in other agreements.

It would be hard to overstate the importance of corn to Mexico’s cultural heritage, both for the general population and for Indigenous peoples specifically. In its rebuttal, the U.S. acknowledges the importance of those commitments but makes a convoluted argument that they don’t matter in this case, in large part because they are overridden by other provisions. If that’s the case, then when would such protections apply?

Is it reasonable to expect Mexico’s farm policies to be stuck in 2020 forever?

In making the argument that article 32.5 should not apply, the U.S. essentially claims it expected Mexico’s policies relating to corn would continue without change after the USMCA went into effect. It asserts that if the panel finds that Mexico’s measures are allowed by the Indigenous rights exception, the measures are nevertheless invalidated under Article 31.2(c) on nullification and impairments. IATP Senior Attorney Sharon Treat, the lead author in IATP’s comments explained,

As IATP stated when the U.S. first invoked this argument, if the Panel were to accept the U.S. interpretation, it would completely undercut the existence of the Indigenous rights general exception and render its protections meaningless and illusory. Mexico’s rebuttal clearly establishes that such an outcome is neither justified by the facts nor supported by WTO jurisprudence. The U.S. interpretation of the USMCA is a slap in the face to Indigenous Peoples who worked hard to include this exception in the USMCA, a provision that was celebrated by both negotiators and Indigenous advocates as a significant advancement in North American trade policy.

The Mexican restrictions on GM corn and glyphosate are essential elements of a national strategy to enhance agroecological production of corn and other basic grains in ways that enhance stability in national markets, reduce emissions and safeguard biodiversity. The growing climate emergency and periodic market crises due to war, disease or sketchy supply chains dominated by monopolistic interests mean that business as usual is not only not an answer; it is absurd. The USMCA text takes some initial steps to create principled flexibility to meet these challenges. The panel should make sure they aren’t wiped away by a failed approach to trade stuck in the past.