Sudan is indispensable to China’s silk road vision for Africa

Global Research | 24 November 2017

Sudan is indispensable to China’s silk road vision for Africa

By Andrew Korybko

The news that China will build a railway from the Red Sea city of Port Sudan to the Chadian capital of N’Djamena proves just how serious Beijing is about pioneering a transcontinental Sahelian-Saharan Silk Road to more easily connect Africa’s largest country of Nigeria to the Eurasian landmass, bringing with it plenty of multipolar opportunities for China’s Pakistani and Turkish partners and showcasing the indispensable position that Sudan is poised to play in making this grand vision possible.

The Sudan Tribute recently reported that its eponymous country signed a deal with China to explore the viability of constructing a railway from Port Sudan to N’Djamena, with an eye on completing a long-awaited connectivity project that had hitherto been held up due to various degrees of regional instability. According to the publication, the original plan was to link up the Chadian and even nearby Central African Republic capitals with the Red Sea in order to provide these resource-rich landlocked states with an outlet to the global marketplace, which is increasingly becoming Asia-centric ergo the Eastern vector of this initiative. In terms of the bigger picture, however, the successful completion of the Port Sudan-N’Djamena Railway would constitute a crucial component of China’s unstated intentions to construct what the author had previously referred to as the “Sahelian-Saharan Silk Road”, the relevant portion of which (the Chad-Sudan Corridor) is a slight improvisation of Trans-African Highway 6.

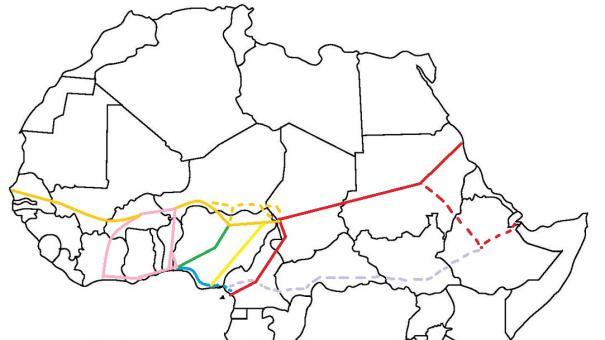

Per the hyperlinked analysis above, the following custom map illustrates the full cross-continental vision that China has in mind:

Red: CCS (Cameroon-Chad-Sudan) Silk Road

Gold: Trans-African Highway 5

Lavender: Ethiopia-Nigeria Silk Road (the most direct route through resource-rich territory)

Pink: West African Rail Loop

Blue: Lagos-Calabar Silk Road

Green: Lagos-Kano Silk Road

Yellow: Port Harcourt-Maiduguri Silk Road

Each of the aforementioned tracks are described in a bit more detail in the cited article about the Sahelian-Saharan Silk Road and the author’s extensive Hybrid War study on Nigeria, but the two pertinent points to focus on in this piece are the CCS Silk Road (outlined in red on the map) and its larger purpose in possibly connecting Africa’s two largest countries and future Great Powers of Nigeria and Ethiopia. One of China’s grand strategic objectives in the emerging Multipolar World Order is to lay the infrastructural groundwork for facilitating the robust full-spectrum integration between these two giants, understanding that their Beijing-built bicoastal connectivity would bestow the People’s Republic with significant influence in the continent by streamlining an unprecedented corridor between them, thereby giving China the potential to more directly shape Africa’s overall development across the 21st century.

It goes without saying that Sudan is poised to play an indispensable role in making this happen by virtue of its advantageous geography in allowing China to circumnavigate the “Failed State Belt” of South Sudan, the Central African Republic, and increasingly, maybe even Cameroon, as well by charting an overland Silk Road connectivity corridor between Ethiopia and Nigeria via Sudan and Chad. Moreover, the potential linkage of the planned Ethiopia-Sudan railway to the prospective Port Sudan-N’Djamena railroad would enable Sudan to provide China with alternative access to these two landlocked states. Regional military leader and energy exporter Chad is already in physical touch with the outside world through Cameroon, just as the world’s fastest-growing economy and rising African hegemon Ethiopia utilizes the newly built Djibouti-Addis Ababa railway for this purpose, but the shrewd and far-sighted Chinese always feel more comfortable if they’re not dependent on a single route, hence the strategic importance of supplementary access to Chad and Ethiopia through Port Sudan.

While Sudan’s financial standing was left reeling ever since the American-backed separation of oil-rich South Sudan in 2011, Khartoum might fortuitously find itself wheeling and dealing along the New Silk Road if it’s successful in providing China with alternative market access to Chad and Ethiopia in the future, and especially if it can do the same with Nigeria in saving China the time in having to sail all the way around the Cape of Good Hope in order to trade with it. For as easy as all of this may sound, however, the premier challenge that China will have to confront is to ensure the security of this traditionally unstable transit space, specifically in the context of maintaining peace in the former hotspot of Darfur and dealing with the plethora of destabilization scenarios emanating from the Lake Chad region (Boko Haram, Nigeria’s possible fragmentation, etc.).

In view of this herculean task, China could be lent a helping hand by its Pakistani and Turkish partners who each have a self-interested desire to this end, with Islamabad slated to patrol CPEC’s Sea Lines Of Communication (SLOC) with East Africa while Ankara is already a heavy hitter in Africa because of its recent embassy and airline expansion in the continent. Moreover, both of these countries are leaders of the international Muslim community (“Ummah”) in their own way and accordingly have soft power advantages over China in the majority-Muslim states of sub-Saharan Africa through which Beijing’s grand Silk Road projects will traverse. Seeing as how Pakistan and Turkey are also on very close relations with China, the scenario arises whereby these Great Powers enter into a trilateral working group with one another for effectively promoting their African policies through joint investments, socio-cultural initiatives, and the collective strengthening of Nigeria, Chad, and Sudan’s military capacities in countering their respective Hybrid War threats.

This is especially relevant when considering that all three transit states aren’t exactly on positive footing with the US. Washington initially refused to provide anti-terrorist assistance to Abuja when it first requested such against Boko Haram in 2014, and the Trump Administration has inexplicably placed N’Djamena on its travel ban list. As for Khartoum, it’s been under US sanctions for over two decades now, even though the State Department partially lifted some of them last month as part of its “carrots-and-sticks diplomacy” towards the country. Therefore, the case can convincingly be argued that these three African countries would be receptive to Chinese, Pakistani, and Turkish military assistance because their prospective Eurasian security partners are perceived of as being much more reliable and trusted than the Americans or French who always attach some sort of strings to their support. The only expectation that those three extra-regional states would have is that their counterparts’ collective stability would be enduring enough to facilitate win-win trade for everyone.

There’s a certain logic to the comprehensive strategy behind this Hexagonal Afro-Eurasian Partnership between Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, Turkey, Pakistan, and China. Nigeria, as the West African anchor state, could help expeditiously funnel the region’s overland trade to the Red Sea via the landlocked Chadian transit state and the maritime Sudanese one, thus making Khartoum the continental “gatekeeper” of West African-Chinese trade. Turkey’s hefty investments and newfound presence in Africa could help to “lubricate” this corridor by making it more efficient, with President Erdogan trumpeting his country’s version of a moderate “Muslim Democracy” at home in order to score significant soft power points with these three majority-Muslim African states and their elites. Pakistan would assist in this vision by providing security between Port Sudan and what might by that point be its twinned sister port of Gwadar in essentially enabling the flow of West Africa trade to China by means of CPEC.

Altogether, maritime threats are kept to a minimum because of the shortened SLOC between Sudan and Pakistan (as opposed to Nigeria and China) while the mainland ones are manageable due to the military-security dimensions of the proposed Hexagonal Afro-Eurasian Partnership, but it nevertheless shouldn’t be forgotten that Sudan and Pakistan are the crucial mainland-maritime interfaces for this transcontinental and pan-hemispheric Silk Road strategy which is expected to form the basis of China’s “South-South” integration in the emerging Multipolar World Order.

Andrew Korybko is an American Moscow-based political analyst specializing in the relationship between the US strategy in Afro-Eurasia, China’s One Belt One Road global vision of New Silk Road connectivity, and Hybrid Warfare.