The whole BIT

Business Today | 11 February 2016

The whole BIT

by Joe C. Mathew

On December 17, 2015, US-based Philip Morris, the manufacturer of iconic cigarette brand Marlboro, lost a legal battle against the Australian government in an international arbitration tribunal. The company was trying to challenge an Australian law, which was legislated from a public health perspective to discourage the promotion of tobacco products. The Australian government had limited the use of brands, logos and trademarks on cigarette packs sold in the country. Philip Morris argued that the law harmed its investment interests in Australia.

The global tobacco giant was empowered to drag the Australian government before a tribunal set up under the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Arbitration Rules on the basis of an agreement that the country had earlier signed with Hong Kong. The Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (IPPA), signed by Australia in 1993, had a provision for an investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism. Foreign investors could invoke this provision to sue Australia or Hong Kong (depending on who invests where) if any policy or regulatory decision in the host country harms the business interests of investors.

Well, technically, the company that complained against Australia was not a US entity. It was Philip Morris Asia (PMAL), a Hong Kong-based corporate body that manages the parent company’s business interests in the Asia Pacific. PMAL also owns 100 per cent equity in its Australian affiliate, Philip Morris Limited. This made it possible for a battle between a Hong Kong company and the Australian government.

The Australian government won the case only because the tribunal felt that it had no jurisdiction to hear the case, prompting Marc Firestone, Senior Vice President and General Counsel, Philip Morris International, to state that the "outcome hinged entirely on a procedural issue that Australia chose to advocate instead of confronting head on the merits of whether plain packaging is legal or even works".

Australia was perhaps lucky, but countries entering into similar bilateral investment treaties with ISDS provisions are not always so. At least, India was not.

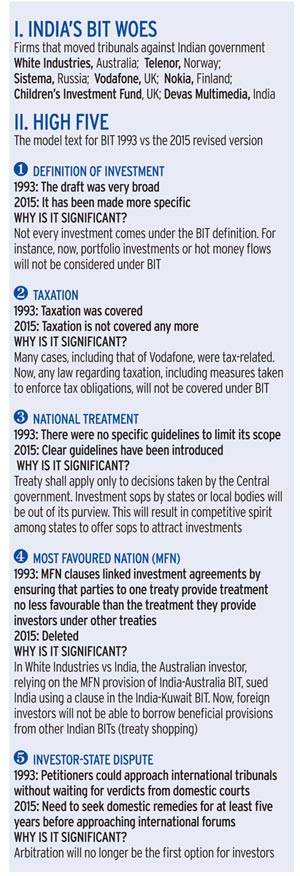

A day before the Philip Morris verdict, on December 16, 2015, the Union Cabinet chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi approved a new model text for the Indian Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT), the Indian version of Australia’s IPPA. India had lost a couple of arbitrations in similar situations and was threatened with many more, simply because the agreements signed on the basis of its existing model draft, a 23-year old draft, had not worked to the country’s advantage. The revision to the text was an attempt to plug the gaps in the earlier provisions. Now, the improved version will not apply to new Bilateral Investment Promotion and Protection Agree-ments (BIPA), but also be used to re-negotiate the existing ones.

India’s Bit Woes

The most recent BIPA-linked case India lost was against one of its own. On September 29, 2015, Bangalore-based Devas Multimedia said that it had won an arbitration in an International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) tribunal against Antrix Corporation - the commercial arm of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO). The tribunal asked Antrix to pay $672 million to Devas for "unlawfully" terminating a February 2011 contract to use spectrum (airwaves) from satellites. The India-Mauritius BIPA came in handy to the three Mauritius-based investment companies, which had owned significant shares in the Indian company. Devas challenged the decision and sought penalties for the lost business opportunities.

This was the second instance where India was being penalised for allegedly not honouring the investment interests of the companies that put in money in the country on the basis of BIPA. In 2011-end, India had tasted the bitter side of BIPA for the first time when an Australian mining company invoked the provisions under the India-Australia agreement to get a verdict in its favour. The White Industries Australia versus Republic of India case resulted in Coal India paying Australian dollar 98,12,077 (around Rs 45 crore) for cancelling a contract it had with its erstwhile mining partner.

Similarly, companies such as Vodafone, Nokia, Cairn Energy and Vedanta have issued notices under BIPA with India against its retrospective taxation moves. The companies alleged that the tax proceedings undertaken by the income-tax authorities under the provisions of the Income-tax Act, 1961, amounted to violation of obligations by India under BIT, and international arbitrations are needed to resolve such disputes that gains strength out of those agreements. Jayant Sinha, Minister of State of Finance, says that the government "neither finds their allegations acceptable, nor agrees with their contention that tax disputes can be resolved under the said agreements". However, he adds: "In order to ensure that the interests of India in such arbitration proceedings are protected, arbitrators have been appointed by the government in accordance with the BIPAs."

The Law Commission of India, in an analysis of the 2015 Model BIT draft, points out that there are 14 pending claims made by foreign investors against India, challenging various regulatory measures, including the cancellation of telecom licences and the imposition of retrospective taxes. The latest status of these complaints is not in public domain as the government wants to explore all possible options to settle these cases out-of-court.

Eighty Three and Counting?

India’s BIT programme began with the country’s attempt to liberalise its economy in the early 1990s. It was meant to increase the comfort level and confidence of foreign investors by assuring a level-playing field in all matters and providing them with an independent forum for dispute settlement by arbitration. BITs, it was hoped, will help project India as a preferred foreign direct investment (FDI) destination while protecting the interests of Indian investors in India’s BIT partner countries.

The first BIT, based on a model text prepared in 1993, was signed with the UK in 1994. Around 50 agreements followed before the model text underwent a few modifications in 2003, to become the basis of future negotiations. Till date, the country has signed 83 BITs, of which 74 are in force. India has also entered into Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), which have a dedicated chapter on investment, and are substantially similar to standalone BITs. Eleven such FTAs are in force.

At present, India is negotiating FTAs containing investment chapters with Indonesia, Australia, Mauritius, New Zealand and the European Union. It is also negotiating with Canada for BIT and has an ongoing negotiation with the US that began in 2009.

The revised model BIT is meant to be used for renegotiations of existing BITs as well as during negotiations of all future BITs and investment chapters in the Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreements (CECA), Comprehen-sive Economic Partnership Agreements (CEPA) and FTAs.

The primary difference between the model text and the existing BIPA version is to provide a sharper, enterprise-based definition of investment, a refined investor state dispute settlement (ISDS) provision, which will force investors to exhaust local remedies before commencing international arbitrations, and limiting the power of tribunals to awarding only monetary compensation. The new model excludes certain provisions, including government procurement, taxation, subsidies, compulsory licences and national security policies, to preserve the Centre’s regulatory authority. But how effective will be the revised text on BIT be in protecting India from future threats?

Kavaljit Singh, Director of the Delhi-based Madhyam, a policy research institute, says that the new text is definitely "better" than the old one, though it will not reduce litigation risks from existing agreements. "We got sued because of the existing version. All 74 BITs are legal documents, and investors can still sue us. Even if these BITs lapse, there is a survival clause attached to it," adds Singh.

Even if a BIT gets cancelled today, the assurances given to investors under that agreement will remain valid for another 10 years. "In other words, even if you renegotiate, it (the provisions in the existing BIT) is enforceable", Singh explains.

Renegotiating the Future

The finance ministry is silent on how it would renegotiate existing agreements. As of now, it seems to be just an intention. The only positive move is the government’s decision to put an end to the practice of allowing the commerce ministry to handle the negotiations on the investment chapter in free trade agreements, and restrict the finance ministry’s role to negotiations on standalone BITs. From December 28, 2015, the Department of Economic Affairs (DEA) under the finance ministry remains the sole authority to lead all negotiations on standalone BITs as well as investment chapters of CECAs, CEPAs and FTAs, to ensure convergence between trade and investment issues among all stakeholders.

Even if the government decides to renegotiate the agreements, it may not be able to get all the 83 partner countries to agree to it. Countries with less diplomatic and financial clout may agree, but the powerful may not. Even if they do, they would try to push their own set of conditions before reaching for a final settlement. The model law, when looked from an inbound investment point of view, needs a lot of improvement. There are still many loopholes for investors to exploit, but perhaps this can be better explained when one comes to realise that the same rules will also be applicable to facilitate outbound investments. If there is something that helps foreign investors in India, the same rules will also help Indian companies invest in India’s BIT partner nations.

In this context, the 2015 model text, for instance, has no provision for the government to sue the investor or company in case of a serious fraud as part of a counter measure. It is true that Indian companies having investments abroad were not very keen to have such a mechanism as that would have subjected them to counter actions from host countries in case of any non-compliance. "Right now the government cannot sue private corporations. It (the proposal) was removed altogether in the final draft. But the clause would have brought some level-playing field," says Singh.

With India’s dwindling export earnings, and slower-than-expected economic growth, the Modi government has announced its plans to speed up its bilateral and multilateral engagements. Whether it will be backed by stronger investment protection and promotion agreements is something that needs to be seen. During the past few years, significant changes have occurred globally around BITs in general, and investor-state dispute resolution mechanism in particular. India is not alone. South Africa is in the process of changing the way it negotiates investment treaties. Indonesia has finalised its draft. But even if India does it, are we shying away from renegotiating the existing agreements?