Trans-local mining activism connects Nevada and Guatemala in growing movement of resource nationalism

Nevada Capital News | 28 May 2019

Trans-local mining activism connects Nevada and Guatemala in growing movement of resource nationalism

by Brian Bahouth and Maribel Cuervo

Reno – On March 2, 2012, Estela Reyes parked her car in the road that leads to the Progreso VII mine. Soon fellow citizens from San Pedro Ayampuc and nearby San José del Golfo, Guatemala joined her blockade of the road that prevented mining equipment from entering the site. Protesters calling themselves La Puya or The Sting cited fouled water and a lack of consultation on the project as primary reasons for this exercise in passive resistance. The mine operator, Exploraciones Mineras de Guatemala or EXMINGUA, is a subsidiary of Reno, Nevada-based, Kappes, Cassidy and Associates (KCA).

The conflicts over Progreso VII and other mines in Guatemala and throughout the world are far from over, and the situation in San José del Golfo is an object lesson in the evolution of shifting power in Central America.

According to Verisk Maplecroft’s 2019 Resource Nationalism Index, some 30 countries are taking greater control of resource extraction on their lands, and though Guatemala is not among the top 30, “creeping resource nationalism,” is among the leading threats to operators, according to the report.

The Verisk Maplecroft’s Index identifies several “indirect forms of resource nationalism” such as rising taxes, shifting contract terms, and more rigorous regulatory environments. The assessment does not apparently consider the effects of local or worldwide activism on the degree and nature of resource nationalism and the resulting outcomes of resource extraction projects.

According to the Guatemala Human Rights Commission, after two years of peacefully maintaining the blockade, on May 23, 2014, “the communities in resistance of La Puya were violently evicted from the entrance to the project; at least 20 people were injured and 7 were taken to the hospital in Guatemala City. Since then, the Guatemalan police and military have escorted mining equipment onto the site.”

Following the confrontation, La Puya activists with assistance from an international contingent of supporters, made a legal challenge to the mine in the Guatemalan legal justice system.

On July 15, 2015, a Guatemalan court ruled in favor of La Puya, ordering EXMINGUA to suspend all activities at the mine pending consultation with local citizens conducted through the Ministry of Energy and Mines (MEM).

In a letter sent to the president of Guatemala Alejandro Maldonado Aguirre dated October 26, 2015, US congressman Raul Grijalva (D-NM) and 11 other members of congress expressed concern that an American company was running roughshod over Guatemalan rule of law to the detriment the local population.

From the letter:

The court ruling clearly states that EXMINGUA has been operating without a valid permit from the municipal government, did not consult with affected communities before the project began in accordance with Guatemalan and International law, and that the company’s Environmental Impact Assessment was plagued with serious deficiencies as highlighted in a letter dated March 14, 2014 from hydrologist Robert Moran.

In February of 2016, the Guatemalan Supreme Court ordered the suspension of mining operations in response to an appeal filed by the Center for Environmental and Social Legal Action of Guatemala (CALAS). CALAS and La Puya successfully argued that the mining license initially issued in September 2011 was done so without an adequate environmental impact statement and consultation with the indigenous population.

KCA president Daniel Kappes told Nevada Capital News that his company met with people who live around the mine and met all environmental impact study requirements.

“We did a complete environmental and social impact study,” Kappes said by phone. “We, before the mine ever opened, we took the mine model out to all the local indigenous communities. We have pictures of that and they’re reported in the in the study. As part of that everybody has the option of filing objections. Nobody filed objections. Everybody, basically plenty of people saw what we were doing, saw the online model. What we’ve done is exactly what we said. Nobody objected to it at the time. As far as I can see, nobody local is objecting to it. The local people are essentially being encouraged to oppose it. But in general, the local people are in favor of the mine. We had 180 employees when we were forcibly shut down, all of whom loved working there in the local communities, basically saying, ‘When are we going to reopen?’”

Alvaro Sandoval is a member of La Puya. Nevada Capital News reporter Maribel Cuervo spoke with Sandoval by phone and translated his responses to English.

“We were never consulted, informed or never asked for any agreement for this project,” Alvaro Sandoval said.

Sandoval explained that those who live near the mine get their water from creeks and wells, and for La Puya, their opposition to the mine is rooted in bad water quality.

“The water in its natural state, it’s contaminated with arsenic and very, very scary,” Sandoval said to Maribel Cuervo. “After the project started, they did a test to the water, and it is very contaminated, highly contaminated.”

A further lack of trust in the mining company in large part stems from EXMINGUA’s failure to abide the July, 2015 court decision ordering the mine to close. Video and photographic evidence show the mine continued to operate and remove ore from the site via helicopter after the order to stop operations on July 15, 2015. We asked Daniel Kappes when his company ceased mining operations.

“The Constitutional Court of Guatemala said we should stop mining, so we stopped mining,” Kappes said. “That was in March of 2016, and we’re waiting for that all to be sorted out.”

According to the Guatemala Human Rights Commission, on April 22, 2016, the Guatemalan Ministry of Energy and Mining (MEM) filed a criminal complaint against EXMINGUA, so Mr. Kappes may be the object of criminal proceedings in Guatemala for failing to honor the order to cease mining operations.

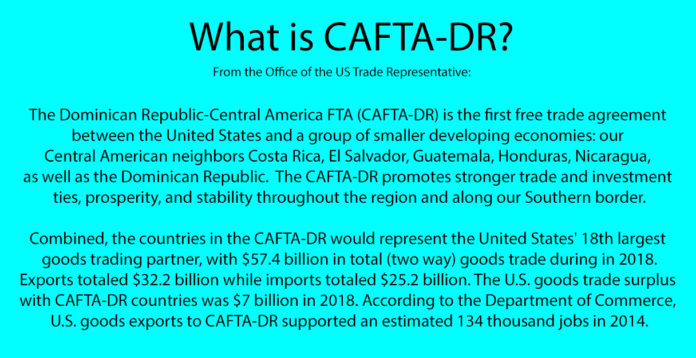

The United Nations ILO (International Labor Organization) Convention 169 was ultimately the basis for the court’s decision to shut down the mine. The convention officially “recognizes Indigenous Peoples’ right to self-determination within a nation-state, while setting standards for national governments regarding Indigenous Peoples’ economic, socio-cultural and political rights, including the right to a land base. The convention is law within the nation-states that have ratified it,” which includes Guatemala. Ultimately the mine operates under the authority of CAFTA-DR, so the dispute will not be settled in court but in arbitration.

The World Bank´s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID)

In December of 2018, KCA filed a $300 million-dollar arbitration claim against the government of Guatemala. Under CAFTA-DR, tribunals decide disputes. Since 1964 the ICSID, under various trade agreements, has enabled corporations to sue nations they believe have wrongfully denied them access to extractive resources. The ICSID has a well documented corporate bias.

Regarding the KCA vs. Guatemala case, as of this writing, both have chosen their representatives for the tribunal, and now the parties must decide who will be the third and “presiding” member of the panel.

For Alvaro Sandoval and La Puya, they mistrust the government and the mining company. They also mistrust the ICSID system of adjudication that in effect punishes Guatemala and other countries for protecting their natural resources and environment. Sandoval says the process effectively silences the voices of the people affected by the mine. He added that the ICSID arbitration is nothing more than a strategy to reopen the mine and have the government avoid the payment of $300 million. According to Sandoval, there are 17 other similar mining projects in northern Guatemala.

“The state already has named a lawyer that is going to represent them, and the company has as well,” Sandoval said. “We have a lawyer, but we don’t know what’s going to happen between those two parties. They’re going to have to choose a third lawyer, a third party, a lawyer, that is kind of going to monitor or oversee the whole the whole process. We’re worried because we don’t know, because we hear the Energy and Mines Commission and Congress want to reactivate this project.”

On April 24 of this year, a letter was delivered to the KCA offices in both Guatemala and Reno and the U.S. Embassy in Guatemala that calls for KCA to drop the arbitration claim and more. Ian Bigley is the mining justice organizer for the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada (PLAN) and hand-delivered the letter to the KCA office in Reno. The letter is sponsored by 12 organizations including PLAN and has endorsements from 227 other groups, agencies and governments.

Ian Bigley said Mr. Kappes was not in the office on the day he delivered the letter but said he would meet with Mr. Kappes to discuss the issue further.

“So we had talked to not just a secretary, but a representative from his office who accepted the letter and listened to our purpose of being there in solidarity with La Puya for these issues and to offer the potential to set up a meeting with Mr. Kappes himself, when he’s back in town,” Bigley said.

Bigley said he and the letters’ signatories were most concerned about the environmental impact of the mine on locals.

“The demands that are highlighted in the letter are, number one, to address the environmental impacts that will be resulting from the mine site. Then they also ask for acknowledgement of this particular quasi-legal body as being detrimental to the benefit of Guatemalan communities. It demands demilitarization of the security and police forces at the site,” Bigley said.

Bullet points from the letter:

- We join in solidarity with the residents of San Pedro Ayampuc and San José del Golfo who are deeply concerned about the grave threat the mine poses to water supplies, ecosystems and the quality of life in the area.

- We express our dismay at how this suit represents a further attack on Guatemala’s judicialsystem. The Constitutional Court is already under pressure as a result of President Morales’ decision to defy the Court’s ruling and expel the UN-backed anti-corruption and antiimpunity body, the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG by its initials in Spanish).

- We call on KCA and the Guatemalan government to refrain from intimidating the Constitutional Court justices and that the cases currently before them be allowed to play out and that decisions be made based on the rule of law. As part of this, we call on KCA to drop its suit.

- We call for the immediate demilitarization of the region, specifically the municipality of San José de Golfo where the military has been deployed since January 2018, roughly one month after KCA filed its case.

- We also support the call from the Peaceful Resistance of ‘La Puya’ that CAFTA-DR be declared detrimental to the wellbeing of the Guatemalan people and denounced as allowed by the Guatemalan Political Constitution, further considering that Guatemala has already had to pay $32.4 million dollars to two US companies (RDV and TECO) and is currently subject to other arbitration claims for hundreds of millions of dollars.

Daniel Kappes said he could not speak for the national police but chuckled when asked if the security personnel at the mine are or have ever been “militarized.”

“We have two security guards,” Kappes said. “Sometimes we have between two and four employees that go out there to do things like essentially monitoring environmental things, drains. We want to make sure that things don’t fill up with water and overflow, so we have people go out there periodically, and there are two guards on the site.”

For Alvaro Sandoval and La Puya there are numerous and important unanswered questions. Will the Guatemalan government stand in defense of its courts and people and pay KCA $300 million to close the mine or will they allow the mine to operate at the expense of locals to prevent such an addition to the roughly $35 million Guatemala has already paid in ICSID arbitration claims to foreign corporations?

The reasons behind growing resource nationalism are global and complex and linked to place and geopolitical circumstance. Ian Bigly is based in Reno and is participating in a global action in defense of La Puya and people in smaller, resource-rich countries everywhere. Bigley believes there is change-making power in global networks made up of many grassroots organizations tied to specific places and offered such a network from the Climate Justice Alliance as an example.

“One thing that I would like to lift up is trans-local organizing, as opposed to trans-national corporations and institutions where we have a lot of this interaction across nations and globally and with the folks who are inhabiting elite positions in our societies, and one of the things that’s so uplifting is seeing this collaborative work as a trans-local network, a group of everyday folks fighting to defend their places, who are able to organize globally and share stories and share power,” Bigley said.

There is no published timeline for the KCA/Guatemala arbitration case. Daniel Kappes said KCA is moving forward with the claim and that the letter PLAN delivered to his office was inflammatory and inaccurate.

“That’s just being very melodramatic to the point of not being honest,” Kappes said of the letter. “Yeah, CAFTA-DR says that if the state of Guatemala essentially takes a property illegally, that you have the right to take Guatemala to court, not court, but arbitration under international arbitration rules.”

For Alvaro Sandoval and the La Puya movement, the goal is to be part of the mine licensing discussion, not to be ignored when voicing concerns about Progreso VII and other nearby mines.

“We [La Puya] are not against progress,” Sandoval said. “We are simply questioning the price we have to pay for this development. We’re fighting for our rights, which are not respected either by the multinational companies or by the Guatemalan Government,” Sandoval said.

According to Daniel Kappes, the mine employed 180 people at the time it was forced to close and was just becoming profitable, but according to Alvaro Sandoval, locals inhabited almost exclusively menial positions at the lowest possible wage. Sandoval added that the mining company has ingratiated itself with several local leaders to further isolate and marginalize opposition to the project.

“We (La Puya) as a resistance, we have no support from any entity,” Sandoval said. “Even the mayors and many local authorities work with this (mining) company, so they manipulate a lot of people because they know that this is going to bring damage to the community, is going to damage the communities.

“For me, the most important thing is that we are fighting for the right, the right to consultation. We are demanding the right that they respect our right to be consulted about this. So even if we lose the hearing, at least we’re standing up for our rights.”

Through working with people around the planet, Alvaro Sandoval has come to see the fight over the Progreso VII as a larger fight with the global environment at stake.

“We ask those people who have a social conscience and they love justice to really support this fight because this is a fight for the conservation of the planet. I don’t think that we need gold. There is a lot of gold in the banks in Europe and in other countries, so we don’t need it. It’s just grief. They want gold to increase their fortunes. What we need is water, not gold, so I ask people to support us because we are not fighting here for a personal interest. We are fighting for a community and for the entire world,” Sandoval said.