Opinion on the establishment of an investment tribunal in TTIP

All the versions of this article: [English] [Español] [français]

DRB | February 2016

Opinion on the establishment of an investment tribunal in TTIP - the proposal from the European Commission on 16.09.2015 and 11.12.2015

Translated by TNI

No. 04/16

A. Tenor of the opinion

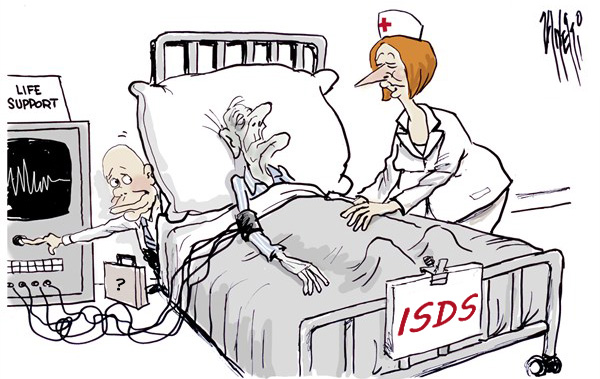

The German Magistrates Association rejects the proposal of the European Commission to establish an investment court within the framework of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). The DRB sees neither a legal basis nor a need for such a court.

The clearly implied assumption in the proposal for an International Investment Court that the courts of the EU Member States fail to grant foreign investors effective judicial protection, lacks factual basis. Should the negotiating partners have identified weaknesses in this area in individual EU Member States, these should be taken up with the national legislature and clearly defined. It would then be up to the legislators and those responsible for the judiciary to provide remedy within the proven system of national and European legal protection. Only in this way can the full legal rights to which any law-seeking party in Germany and the European Union is entitled, be guaranteed. The creation of special courts for certain groups of litigants is the wrong way forward.

B. Review in detail

The European Commission’s proposed Investment Court System (ICS), that is to be integrated into a system of mediation and consultation, would be responsible for claims relating to breaches of investor protection clauses included in the Treaty (Art. 1(1)). According to the definition in the proposed text, investments extend to any type of asset, including stocks, shares in companies, intellectual property rights, movable property and receivables (Chapter II, Definition x2). The legal protection of investment thus extends from civil law through to general administrative law and social and tax legislation. The Commission’s proposal would mean that an ICS would obtain a judicial competence in these areas in order to ensure comprehensive protection of the investor, who should be able to resort to ICS when incurring losses through a breach of investor protection rights (Art. 1(1)).

Missing legislative competence

The German Magistrates Association has serious doubts whether the European Union has the competence to institute an investment court. The establishment of an ICS would oblige the European Union and the Member States, upon the conclusion of an agreement, to submit to the jurisdiction of an ICS and the application of certain international procedures chosen by the plaintiff (art. 6 para. 5 subpara. 1, art.7 para. 1). The decisions of the ICS are binding (art. 30 para. 1).

An ICS would not only limit the legislative powers of the Union and the Member States; it would also alter the established court system within the Member States and the European Union. In the opinion of the German Magistrates Association, there is no legal basis for such a change by the Union. As the European Court stated in its Opinion 1/09 of 8 March 2011 on the establishment of a European Patent Court, the Union maintains "a complete system of legal remedies and procedures designed to ensure review of the legality of acts of the institutions (para. 70 )". Like the proposed Patent Court that was then being assessed, the ICS would be a court which would be "outside the institutional and judicial framework of the Union" (para. 71).

Like the Patent Court, it would be “an organisation with a distinct legal personality under international law”. It is clear that if a decision of the ICS were to be in breach of European Union law, that decision could not be the subject of ‘’infringement proceedings’’ nor could it give rise to ‘’any financial liability on the part of one or more Member States’’ (para. 88). Consequently, an ICS would “deprive courts of Member States of their powers in relation to the interpretation and application of European Union law and the Court of its powers to reply, by preliminary ruling, to questions referred by those courts and, consequently, would alter the essential character of the powers which the Treaties confer on the institutions of the European Union and on the Member States and which are indispensable to the preservation of the very nature of European Union law” (para. 89).

The German Magistrates Association sees no need for the establishment of a special court for investors. The Member States are all constitutional states, which provide and guarantee access to justice in all areas where the state has jurisdiction to all law-seeking parties. It is for the Member States to ensure access to justice for all and to ensure feasible access for foreign investors, by providing the courts with the relevant resources. Hence, the establishment of an ICS is the wrong way to guarantee legal certainty.

In addition, the German Magistrates Association calls on the German and European legislators to significantly curb recourse to arbitration within the framework of the protection of international investors.

Independence of judges

Neither the proposed procedure for the appointment of judges of the ICS nor their position meet the international requirements for the independence of courts. As such, the ICS emerges not as an international court, but rather as a permanent court of arbitration.

The Magna Carta of Judges of the CCJE of 17 November 2010 (CCJE (2010/3) calls for the legally secured independence of judges in professional and financial terms (para. 3). Decisions on their selection, appointment and career must be based on objective criteria and be taken in such a way as to ensure the independence (para. 5). The ICS meets neither criteria. The decisions to be taken by the ICS would not only relate to questions of civil law, but the administrative, labour , social and fiscal law would also significantly come into play. Selecting the judges of the ICS from the group of experts in public international law and international investment law with experience in the resolution of international commercial disputes (art. 9 para. 4) considerably narrows down the pool of candidates and sets aside the indispensable expertise in each relevant national sectoral legislation. The pool of judges will be limited to the circle of persons already professionally predominantly engaged in international arbitration. This impression is reinforced by the fact that the selection process is not yet outlined in detail. Nevertheless, it will depend on the independence of the selection committee and its distance from the international arbitration to what extent a top selection of national lawyers with specialist knowledge of the relevant fields of law is ensured. So far at least, this is in no way guaranteed.

In addition, a term of office of six years with the possibility of a further term of office, a monthly base salary ("retainer fee") of approximately € 2,000 for the judges of first instance and € 7,000 for those serving on the Appeal Tribunal, plus an expense allowance in the event of actual service (art. 9 para. 12 and art. 10 para. 12) cast doubt on whether the criteria for the technical and financial independence of judges of an international court are fulfilled.