Free trade and debt: the two sides of neocolonialism

All the versions of this article: [English] [Español] [français]

16 November 2023

Free trade and debt: the two sides of neocolonialism

by bilaterals.org

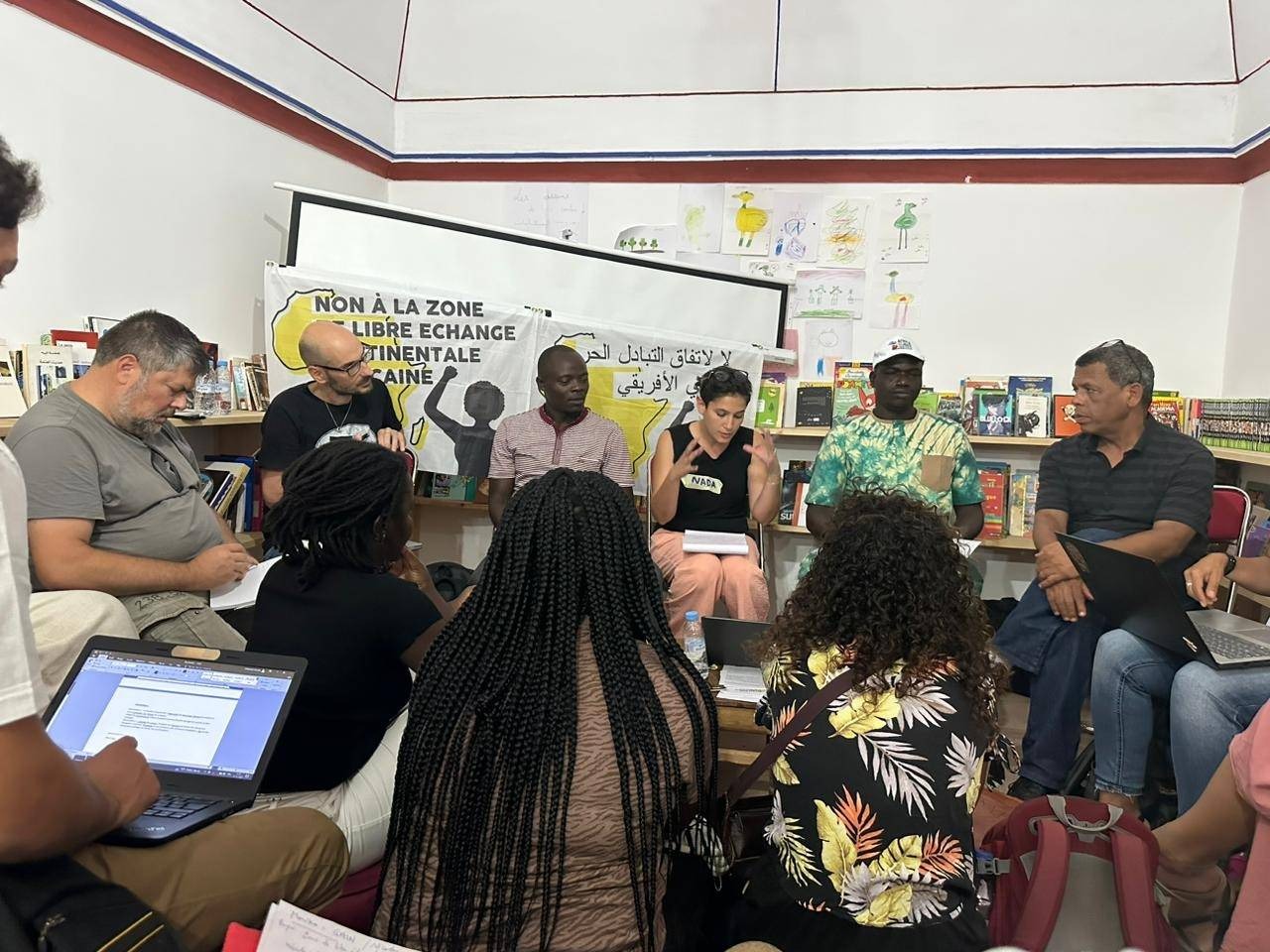

Highlights from the workshop organised in Marrakesh by Attac Maroc, bilaterals.org, CADTM Africa, GRAIN and the Tunisian Observatory of Economy, during the Global counter-summit of social movement convened on the occasion of the annual meetings of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank in October 2023.

"Free trade and debt are not just about money," said Attac Maroc. There is a logic of domination behind them. Debt has historically played a central role in the colonial system in Africa, while international trade has been hijacked by imperialist powers to advance their interests.

At the end of the 19th century, for example, France, Spain and Britain all had their eyes on Morocco and wanted to control it. In 1856, Britain pressured Morocco into signing a trade agreement that allowed the British to penetrate the Moroccan market, giving them a commercial advantage over their local counterparts.

The imposition of the French protectorate in 1912 was the final blow to Morocco’s sovereignty, which was unable to resist European encroachment. Soon after, the weakened country faced droughts and needed aid to deal with the situation. Morocco then became indebted to the colonial powers. The debt increased as a result of colonialism and the construction of infrastructure to serve colonial interests. By the time of independence in 1956, Morocco was one billion dirhams in debt.

In the 1980s, the implementation of neoliberal policies under the structural adjustment programmes of the World Bank and the IMF, which led to massive privatisation, had a devastating impact on the daily lives of the Moroccan people. In addition, free trade agreements, such as those signed with the European Union and the United States, increased the country’s trade deficit, which in turn reduced the income of the Moroccan economy.

The case of Morocco shows how closely debt and free trade are intertwined. Debt in the global South has increased the push for free trade agreements, which in turn has reinforced Southern countries’ dependence on rich economies.

ICSID, the World Bank’s lesser-known institution

Before the triumph of neoliberalism, international trade was used by European countries as an instrument of geopolitical and commercial domination for the past 500 years, as bilaterals.org recalled. Colonial companies and states joined forces to conquer territories and impose legal regimes that benefited Europeans. For instance, Hugo Grotius, considered one of the fathers of international law, was a lawyer for the Dutch East India Company.

In this sense, colonialism was as much about the conquest of territory and the exploitation of wealth as it was about the imposition of trade rules based on European notions of wealth, the environment, and so on. For example, during the colonial era, Europeans created special tribunals to settle trade and investment disputes related to their activities in colonies.

Since decolonisation, the World Bank has played a central role in continuing this parallel judicial system. In 1965, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), part of the World Bank Group, was established on the basis of principles drawn up by Hermann Josef Abs, a German banker, and Hartley Shawcross, a British oil industry executive. ICSID provides an arbitral tribunal to resolve disputes relating to foreign investments. Bilateral investment treaties and free trade agreements include references to ICSID in the event of a dispute between a state and a foreign investor protected by such an agreement. This process is known as investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS).

The ISDS mechanism has been criticised by social movements around the world as it has caused terrible suffering in many countries of the global South. In South Africa, for example, European investors challenged a law aimed at redressing the inequalities of the apartheid era, and succeeded in getting the law watered down so that their profits would not be affected too much. Pakistan was also ordered to pay six billion dollars to an Australian company for cancelling a mining concession contract that the country’s Supreme Court had ruled illegal, even though the company had only invested about $200 million. There are over a thousand such claims around the world, wreaking havoc on populations, the environment and countries’ finances.

When people’s resistance defeated the Tunisia-EU FTA

ISDS was at the heart of the negotiations between the European Union (EU) and Tunisia on a “Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement” (DCFTA), which has so far failed to win the approval of the Tunisian side.

According to the Tunisian Observatory of Economy, the DCFTA was meant to further the economic liberalisation already implemented by the 1995 Association Agreement between the two parties. A neocolonial attitude on the part of the Europeans could be felt during the negotiations, as the trade agreement was more about imposing European interests than having an agreement that could be truly beneficial to both sides.

European negotiators argued that the DCFTA would lead to a harmonisation of standards between the parties, but it was more about Tunisia agreeing to implement European regulations. For instance, the EU pushed Tunisia to accept European standards on sanitary and phytosanitary measures. The EU also tried to lure Tunisia with financial aid, which the country needed to deal with the debt that had grown since the 2011 revolution, as a condition for signing the FTA.

A sense of coercion was felt throughout the negotiations, leading to a large movement of resistance in Tunisia. "Even deep in the countryside, everyone understood that the trade agreement was lopsised," the Observatory insisted. For example, the EU could subsidise its agriculture, but Tunisia could not. A broad coalition managed to derail the agreement by organising protests, lobbying and public relations work, demanding parliamentary accountability and blocking negotiations. Ultimately, the DCFTA was shelved and negotiations have not resumed since.

EPA = Economic Pauperisation Agreement

The situation in Kenya is different, as Kenya signed an Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) with the EU in June 2023. The EPA was originally supposed to be signed with the entire East African Community regional bloc, and negotiations were completed in 2014. But Tanzania, Uganda and Burundi refused to sign. Under pressure from the EU, Kenya finally agreed to the deal on its own. As the only non-least developed country in the East African bloc, Kenya stood to lose preferential access to the EU market. Kenya had also accumulated debt over the years, the Kenyan Peasants League pointed out, and the EPA package came with a development fund.

The EPA will strengthen export-oriented and monoculture agriculture in Kenya, undermining the country’s food sovereignty and putting local producers in unhealthy competition with highly subsidised European companies. The League added that tomato farmers in Ghana were suffering from imports of cheap European produce. Chicken farmers in Cameroon have suffered the same fate. Both countries have EPAs with the EU.

There are also concerns from neighbouring countries that Kenya could act as a gateway to the East African common market and, more broadly, to Africa. When EPAs came into force in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, EU products found their way into the common market area of the Economic Community of West African States.

These are some of the reasons why EPAs have earned the sobriquet "economic pauperisation agreements".

The AfCFTA trap

While social movements have been vocal in their opposition to the EPAs, another neoliberal project is looming over the African continent: the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

The idea of creating a Africa-wide free trade area emerged in 2012 as an initiative of the African Union (AU). The agreement was signed in 2018, but some of its trade rules have only been implemented since October 2022 and between just seven states. As of today, Eritrea is the only AU state that has refused to sign.

The AfCFTA aims to liberalise 90% of non-sensitive products and establish a common external tariff with the rest of the world, explained CADTM Africa.

Under the guise of pan-Africanism, the AfCFTA is built on the dogma of free market capitalism. It promotes an export-led development model. It includes trade rules found in bilateral agreements that benefit elites and transnational capital at the expense of local communities.

Someone in the audience from Mali remarked that free trade zones have been very problematic in her country. They have had a negative impact on communities and have encouraged land grabbing. In addition, there has never been any kind of public consultation or information sharing on the implementation of these zones.

Now, the AfCFTA promotes the expansion of operations in free trade zones to further promote so-called development, while it has been argued that regional integration in Africa should rather be built on the original pan-African principles of solidarity and complementarity to stop the bleeding.

Towards just societies

The workshop concluded that social movements, communities, citizens, etc. need to build a power struggle to reverse the trend. In Côte d’Ivoire, local people protested against the arrival of the Auchan supermarket, which led to the closing of local shops, and boycotted the French company. A similar public campaign also targeted Auchan in Senegal. Such product boycotts can have an impact on large foreign companies.

Ultimately, this is a global issue, not just an African one. The plundering of resources is everyone’s problem. To defeat imperialism, Thomas Sankara said everyone should consume and eat local. Debt and so-called "free trade" have been instrumental in imposing a neocolonial system of domination based on ever more exports and dependence on extractivism. Favouring the local over the international could well be one of the alternatives for societies to face the challenges of our time, including the climate crisis, migration, food and energy sovereignty. International mobilisations such as this counter-summit allow people from all over the world to connect and raise awareness on global issues, thus playing an important role in building solidarity for social justice.